He is often portrayed as the embodiment of the so-called ‘British Bulldog’.

The cigar smoking, champagne drinking ‘V for Victory’ signing Second World War leader who stood defiant against the dark forces of Nazism and led Britain out of bloody conflict into the post-war era.

But a century after Winston Churchill lost his Dundee seat after 14 years as an MP for the city, have contemporary political events of the last decade – chiefly the 2014 Scottish independence referendum and Brexit campaign – “hijacked” the perception of his legacy in Scotland?

At a time when the Black Lives Matter campaign has seen his views on race and colonialism scrutinised like never before, have myths grown up around his Dundee defeat to god-fearing teetotaller Edwin Scrymgeour at the 1922 General Election?

‘Myths and falsehoods’

Edinburgh-based writer and political consultant Andrew Liddle thinks so.

In research for his new book ‘Cheers, Mr Churchill! Winston in Scotland’, the 33-year-old former Courier journalist says he discovered many “myths and outright falsehoods” about Churchill.

Growing up in London, Andrew came to Scotland to study history at St Andrews University.

After a stint doing the Press Association journalism training course in London, he joined Courier publisher DC Thomson in spring 2013.

After two years at The Courier that saw him go from trainee reporter to lead Dundee reporter, he worked for a spell as political correspondent for the Press and Journal at Holyrood before two years working with the Labour Party then two years doing political and economic work at the US Consulate in Edinburgh.

Andrew always had an interest in politics and history.

His grandfather George Thomson was Labour MP for Dundee East from 1952 to 1972 before becoming Britain’s first European Commissioner.

Andrew’s great aunt lived in Dundee and he’d visit the city from London as a child.

It was while doing initial research for his book, however, that he came across the only other book ever written about Churchill’s time in Dundee – A Seat for Life – published in 1980.

When he bought the book and discovered his own MP grandfather had written a preface for it, it was then he thought he “might be on to something”.

Churchill and Dundee

There’s often a perception that Churchill had an “antagonistic” relationship with Dundee.

But the more he researched, the more he realised that this important part of Churchill’s life was “really under appreciated”.

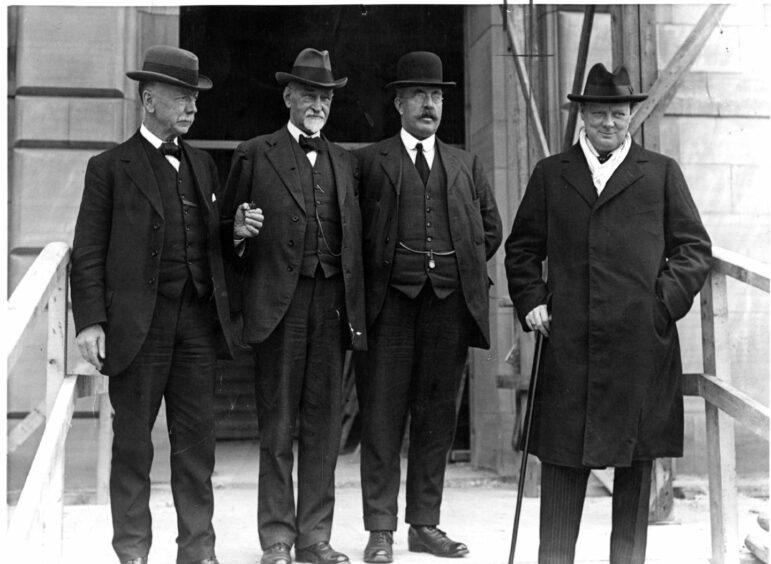

Andrew’s book explores how in 1922, Winston Churchill prepared to defend his Dundee parliamentary seat in the General Election.

He had represented the city since 1908, enjoyed a majority of more than 15,000 and, after five previous victories, confidently described it as a “life seat”.

But in 1922, after five previous attempts to unseat Churchill, Edwin Scrymgeour defeated the incumbent and became the only prohibitionist ever elected to the House of Commons.

So why did Churchill lose?

“It’s a really interesting question that I’d break down into two categories,” Liddle says.

“There’s the national political environment.

“I think the important thing to remember in the 1922 General Election was the Liberal Party was split.

“There were two competing Liberal parties –the national liberals under Lloyd George of which Churchill was a part, and obviously there were the Asquithian liberals as well.

“There were two competing liberal brands fighting each other on a national level which obviously is never really going to be conducive to securing widespread public support.

“But more specifically related to Dundee was that Churchill’s constituency had been particularly based around the working class, jute mill industrial vote, and also the immigrant Irish vote.

“Basically in the period between 1918 and 1922 events in Ireland and events in Russia created the perception – some based on reality and some exaggerated –that Churchill was anti-Irish and an opponent of Irish self-determination and obviously extremely anti-Bolshevik.

“That I think damaged his electoral base quite significantly in Dundee.

“But then the second point I’d make away from those national issues is the local issues.

“Scrymgeour was an extraordinary character. He fought Churchill on six occasions. He was defeated by Churchill five times. But he still kept going and he still kept working the constituency.

“He kept building and expanding his base. And ultimately that paid dividends in ‘22”.

Dundee drink problem?

With high levels of poverty persisting amongst the working classes in the immediate aftermath of the devastating First World War, Dundee had a serious problem with drunkenness and this was widely recognised, says Andrew.

Churchill himself was very concerned about it, and the idea of complete abolition of alcohol in that period was not that novel.

That said, Liddle doesn’t think prohibitionism was a significant factor in Scrymgeour’s success.

After 1922, several local referendums to ban alcohol sales in Dundee were resoundingly defeated.

Instead, he thinks it was Scrymgeour’s socialist ticket that had greater resonance with voters.

Another “myth”, says Liddle, is that Churchill never forgave Dundee for voting him out.

During his research, he concluded this view was “quite misplaced”.

“I think if you look at Churchill’s remarks in the immediate aftermath of his defeat, he was particularly generous to Scrymgeour.

“In the following years, he wrote a reflection of his times in Dundee and his campaigns in Dundee.

“He speaks very warmly of Scrymgeour and indeed of Dundee, as he does in speeches following.

“I think the perception there was an animosity is not something that’s particularly born out actually in the evidence.”

Freedom of the City

Andrew says much of the perception of animosity between Dundee and Churchill stems from Churchill’s rejection of the Freedom of the City in 1943.

“The general kind of view is that Churchill rejected it out of hand because he resented the city for voting him out in 1922,” he says.

“What I discovered in my research is there’s a lot more complexity to the story than that.

“Obviously the vote itself amongst Dundee councillors was split. There was only a majority of one in favour of awarding the Freedom of the City to Churchill.

“But the letter sent offering the freedom of the city, actually went to Tom Johnston, a Labour member of Parliament – and himself a former Dundee MP (1924-29) – who acted as secretary of state for Scotland in Churchill’s wartime national government.

“Johnston advised Churchill to reject the Freedom of the City being offered because it wasn’t delivered unanimously.

“He viewed this, particularly in the context of the Second World War, and fight against Nazism, as an insult that should be rejected. He advised Churchill as such.

“It wasn’t so much that Churchill was rejecting it out of hand. It was actually following the advice of his Secretary of State for Scotland.”

Sources for the book

In terms of sources for his book, Andrew says he was “very fortunate” that the Churchill archive is fantastic and digitised.

But the local history centre at the Wellgate in Dundee was also “fantastically helpful” as were the archives of Courier publisher DC Thomson.

In his days as Dundee MP, Churchill had an “ok relationship” with the local media.

However, when the original David Couper Thomson became an opponent of the Liberal-Conservative coalition, Churchill began to “resent” the way he was “attacked” by the Dundee media and various spats followed.

“He didn’t help the relationship by first of all trying to cajole and then actively threaten DC Thomson,” he says.

“Churchill, David Couper Thomson claims, threatened to set up a rival newspaper group in Dundee to try and damage the circulation of DC Thomson because he was resentful of coverage.

“There’s the famous exchange when Churchill has a go at DC Thomson in his 1922 speech.

“DC Thomson has a go back and publishes the correspondence between them which includes attempts by Churchill to influence coverage.

“But the really interesting thing is they were published after the polls were closed in the 1922 election.

“Even though DC Thomson really wanted to show Churchill had sought favourable coverage, DC Thomson didn’t want to be perceived to be influencing the outcome of the election.

“I think that’s quite an honourable thing.”

Prism of contemporary events

Andrew says there’s no doubt that in the Scottish context, Churchill’s legacy is seen through the prism of contemporary events.

Originally this was from the perspective of left and right. But more recently it’s been from a pro and anti-independence perspective.

“I think initially Scrymgeour’s victory in ‘22 and Churchill’s defeat was viewed as an indication that Scotland was perhaps more left wing than the rest of the UK,” says Andrew.

“This was seized on by Labour politicians as Scotland rejecting conservatism.

“Of course that ignores the fact Churchill was liberal at the time. But no one in popular opinion remembers Churchill as a liberal – they think of him as 1940 and the bulldog conservative.

“I think in more recent times because Churchill is such an iconic almost emblematic British figure, his legacy has become a casualty of the independence debate.

“I think both sides have sought to use his legacy to imply contemporary political relevance.

“I think anti-independence activists will point to the fact Churchill was elected five times in Dundee to show that actually Scotland isn’t anti-British.

“Equally pro-independence activists will point to the fact he was defeated in 1922 as evidence Dundee and Scotland rejected this Britishness.

“I think that’s particularly the case nowadays.

“Given political events in Scotland in the last 10 years in relation to the independence debate, I think a lot is to do with people having a perception of Churchill based on their current politics rather than the reality and therefore when the reality doesn’t quite meet their expectations, basically seeking to change the reality rather than change their perception.”

How to get the book

*Cheers, Mr Churchill! by Andrew Liddle is published by Birlinn, £20, on October 6.

Conversation