Cox’s Stack has remained a constant in Lochee while all around it has changed.

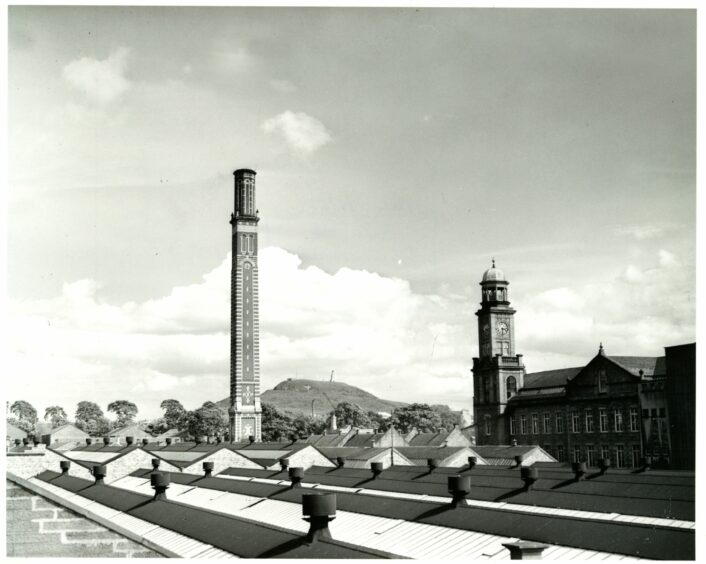

The 282-foot chimney was the landmark for what would become the largest and grandest jute works in the world.

It is now a relic of Dundee’s once-buoyant jute industry.

Cox’s Stack remains a remarkable monument to Victorian engineering and stood firm when Camperdown Works closed in 1981.

When the Stack Leisure Park – named after the chimney – emerged from the rubble in 1993 the chimney found itself at the centre of a legal battle.

That’s because Cox’s Stack almost ended up with a neon sign above it, something that might have looked more at home in Las Vegas than Lochee!

It’s a forgotten chapter in this chimney’s story of survival.

Cox’s Stack

But let’s go back to the start.

The Stack was built in 1865-66 for the enormous jute factory that was constructed by the Cox Brothers in Lochee.

It was designed by the youngest of the brothers, George Addison Cox, who was an engineer, with architectural assistance from James MacLaren.

Dundee-bred Edward Cox inherited Cox Brothers, the family firm, after his father died in 1885.

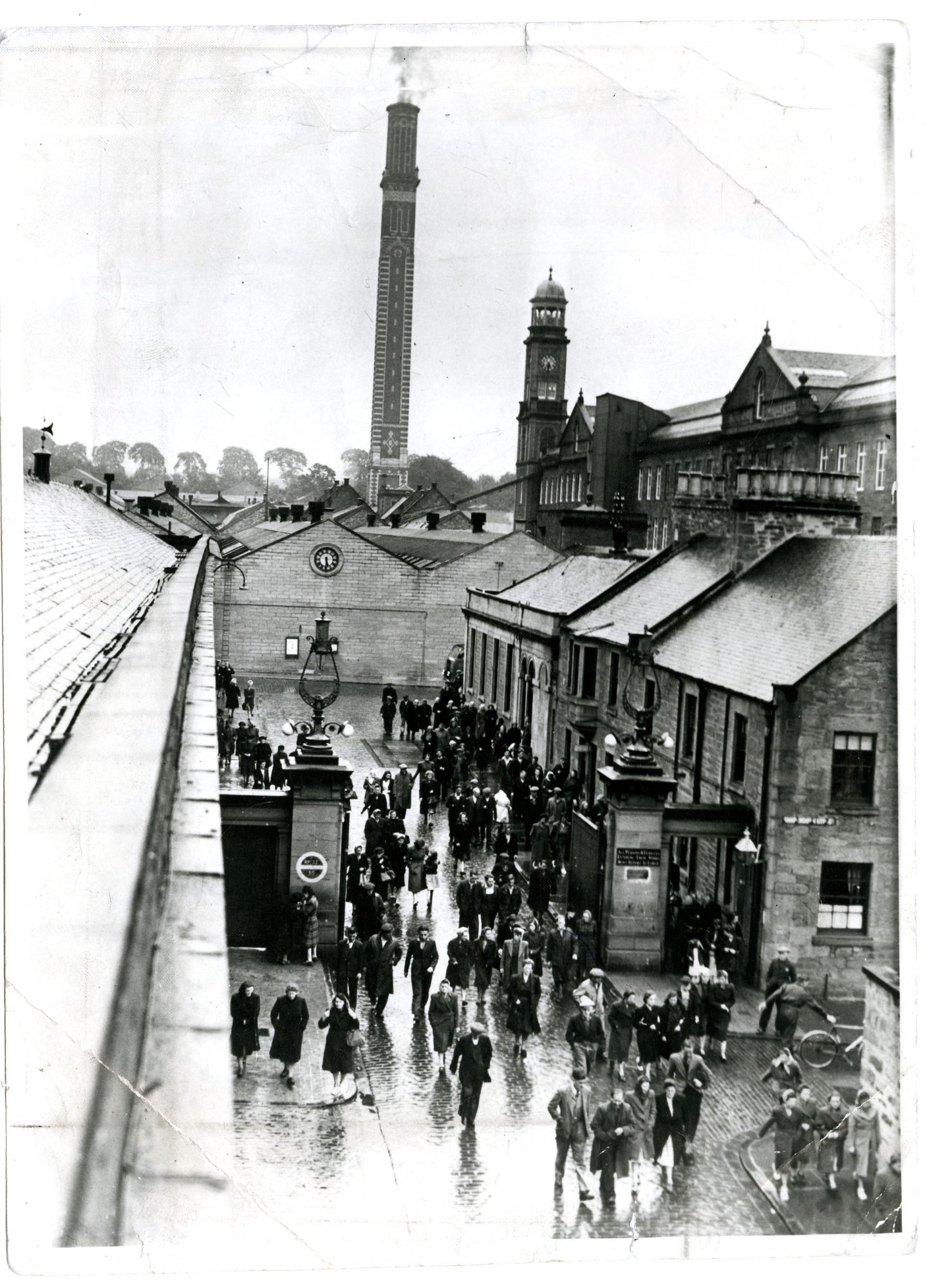

By 1900 the Cox Brothers’ Camperdown Works in Lochee employed more than 5,000 people.

It was one of Britain’s greatest industrial complexes.

Camperdown was so big it had its own branch line, railway station and school.

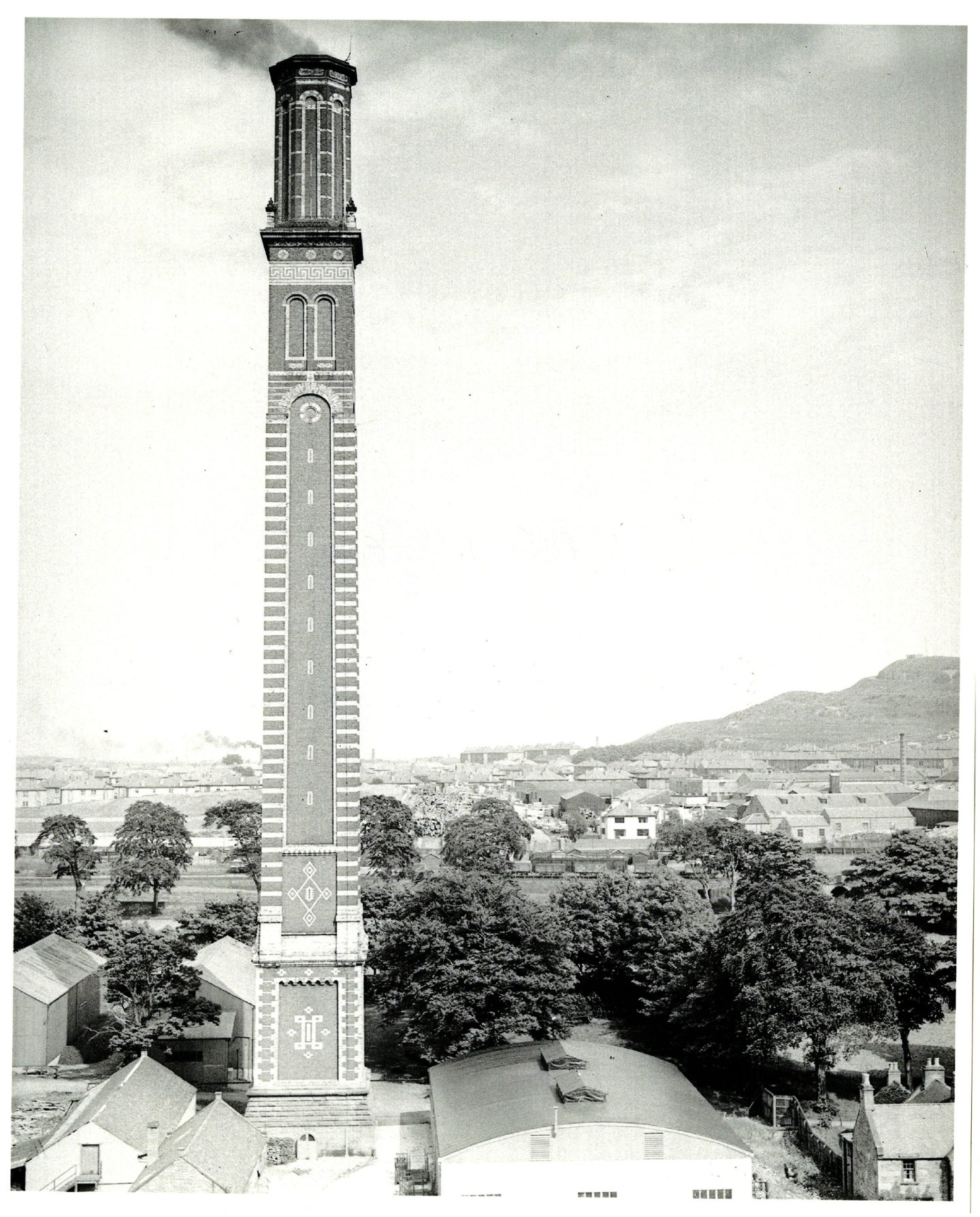

The works covered 25 acres and were dominated by the chimney stalk, said to be made from a million bricks.

Underground tunnels fed the chimney from 58 furnaces.

The looming structure served as a striking visual metaphor for the premier place the Cox Brothers occupied in Dundee.

Mark Watson from Historic Environment Scotland wrote a 1990 book on Dundee’s jute mills where he described Cox’s Stack as the “finest chimney in Scotland”.

He added: “Its exuberance is second to none.

“The Cox Brothers chose to remind their competitors of their presence in Dundee by replacing their three existing chimneys with one stack of stupendous size.

“Engineer George Cox and architect James MacLaren produced a 282 ft-tall campanile.

“It is one of the UK’s three major Italianate chimneys.

“With the Cox Stack, the Cox Brothers were at the forefront of the campanile wave.

“They were potentially inspired by Sir Robert Rawlinson’s 1859 treatise promoting chimneys in the form of campaniles and minarets.

“But the better stacks owe a more direct debt to medieval and renaissance Italy.

“Italian medieval and renaissance campaniles are characterised by their sheer verticality.

“The Cox tower was made of red, white, and black bricks, and had tiny false windows to emphasise its verticality.

“Its foundations were 13 ft deep and 35 ft square.”

Mark further describes how the Camperdown Works were unrivalled in their success, with the chimney overseeing decades of good progress.

He said: “At its peak, the Camperdown Works employed more than 5,000 people.

“Its nearest Dundee rival was the Dens Works, which only employed 4,500.

“Elsewhere in Scotland, only Ferguslie and Anchor Mills in Paisley were, in the 1890s, to approach 5,000 employees in a single textile works.”

Despite these booming operations, the jute industry was hit by a series of slumps in the 19th Century, and fell into decline in the 20th Century.

Edward Cox died from pneumonia, aged 64, in 1913 at his Cardean estate in Meigle, Perthshire, with a £700,000 fortune – worth about £62 million in today’s money.

By 1920 Cox Brothers was one of several Dundee firms which had come together to form Jute Industries (which later became Sidlaw Industries).

Under the chairmanship of James Ernest Cox, Camperdown remained one of its key works.

By 1950 there were only 39 jute firms left out of a total of 150 at the industry’s peak.

Polypropylene had by this time been introduced as the new backing for carpets – at the expense of jute.

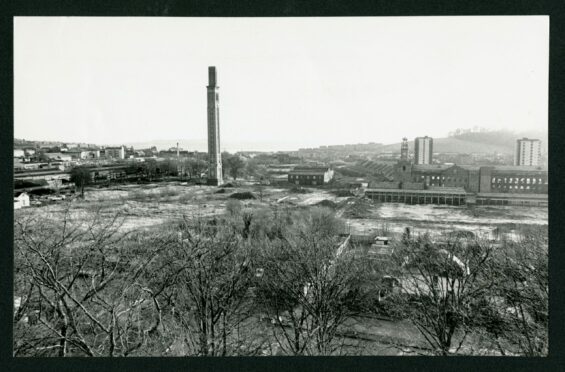

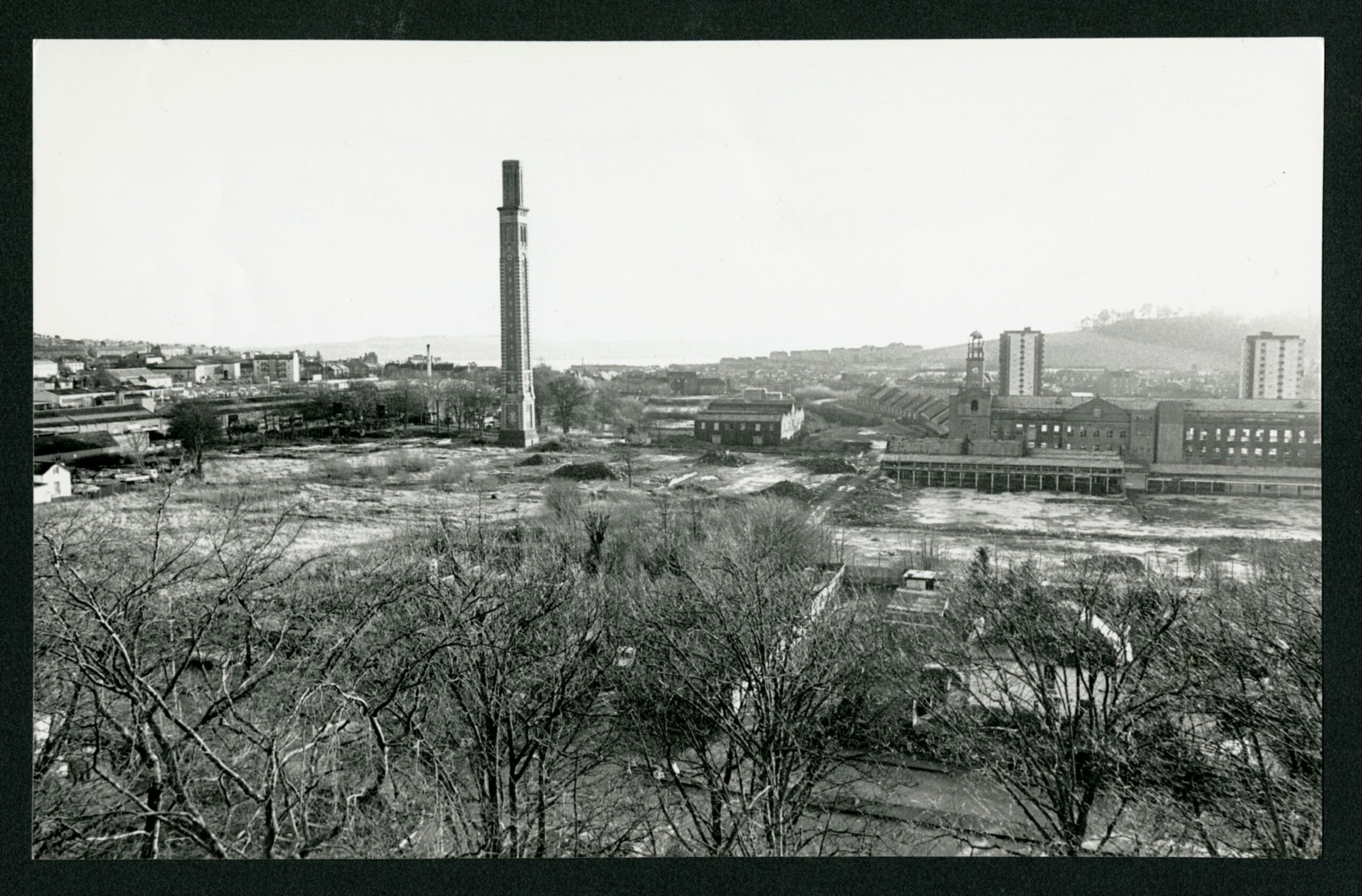

Following the closure of the Camperdown works in 1981, some parts of the complex were sold for demolition in 1985.

In 1988 its battle-weary condition meant it was the perfect choice for producers and it made its TV debut as the backdrop for one of the BBC’s new programmes.

With much of the complex covered in rubble from the ongoing demolitions, the BBC used the site to double for a bombed-out wartime Berlin in its mini-series Christabel.

In 1991, amidst the Camperdown Works redevelopment, a planning request was submitted by the developers to the district council to plant a giant illuminated sign atop the Stack.

The high-tech sign would be imported from America at a cost of £1.63 million.

It would then cost a further £600,000 to build and would provide advertising for multi-national firms.

The sign would be visible from several miles away and operate for 24 hours a day.

Planning permission for the 15-metre by 10-metre advertising sign was first refused in August 1991, after local councillors said it would “challenge the dignity of the chimney”.

However, developer Michael Johnston appealed against the decision.

A public local inquiry was then held in 1992.

Mr Johnston told the council at the inquiry it was his intention to have the sign in place for 15 years.

Income from the advertisements would then pay for any preservation work that needed to be done on the chimney.

Mr Johnston then sent a videotape to the council, which showed the new sign superimposed over the Stack.

It would form the centrepiece of his redevelopment.

The situation was passed to the Scottish Office for final deliberations.

It was 1994 before it reached a decision.

The Scottish Office was the subject of extreme criticism over the length of time it took to make a decision on the new sign.

However, in March 1994, Historic Scotland confirmed it had turned down the appeal.

The proposal was eventually refused due to the chimney’s international importance.

Cox Stack’s iconic Italian architecture saw it made a category A-listed building, and it was decided that the addition of a sign would challenge its integrity.

It was also dubbed a scheme with “overwhelming disadvantages, and was an intolerably high price to pay for limited long-term benefits” by the Scottish Secretary.

The decision to let the chimney remain as it was was largely welcomed by the council and Dundonians alike.

In 1993 the Stack Leisure Park opened – without its new sign.

The iconic Cox Stack chimney was retained untainted as a landmark to link the new commercial area with its history.

By the mid-1990s the clatter of the looms in Tay Spinners was the only sound of Juteopolis still to be heard in Lochee.

In 2015 Dale Summerton from Kirkton debunked the legend that it would be possible to drive a horse and cart round the ledge of the chimney.

He made the discovery while filming the famous tower with a drone.

The owner of computer repair company 3000rpm filmed every angle of the stack on Easter Sunday and managed to get one crucial shot that debunks the myth.

While other parts of the Camperdown site were demolished, several buildings survived and were ultimately converted for other uses.

Cox’s Stack was among them and remains a much-loved feature of Dundee’s skyline.

Conversation