Michael Alexander speaks to author and former Shetland fisherman John Goodlad whose new book The Salt Roads explores 300 years of fishing history traversing the North Atlantic to Eastern Europe.

There are few fishers and fish farmers in Shetland today whose ancestors were not fishermen, beach boys, coopers or gutters.

However, while the Shetland fishing industry is smaller than it once was, it’s still worth more than £300 million per annum and is arguably more efficient and technologically advanced than ever before.

Seafood career

Shetlander John Goodlad is one such man who comes from a long line of Shetland fisher folk.

Born and bred in Shetland, he left to study geography at Aberdeen University before returning to embark upon a career in the seafood industry.

A former fisherman, he was the voice of the Shetland fishing industry as CEO of the Shetland Fishermen’s Association for many years before becoming a fish farmer.

Today he advises several national and international seafood organisations and companies.

His previous book, The Cod Hunters, was shortlisted for the Maritime Foundation’s Mountbatten Award for Best Maritime Book in 2020.

Now, in his latest book The Salt Roads, he explores how, in centuries gone by, salt fish from Shetland became one of the staple foods of Europe.

The book takes the reader to the wild waters of the North Atlantic and tells the story of how over the centuries the Shetland fishing industry not only inspired and affected the islands’ culture, but also shaped people far beyond its shores.

Three iconic fisheries

“The book tells the story of three iconic fisheries in Shetland – the Haaf, cod and herring boom,” John tells The Courier.

“The so-called Haaf– the old Norse word for deep ocean. This was the old fishery by open boats, fishing around Shetland. They began the salt fish business.

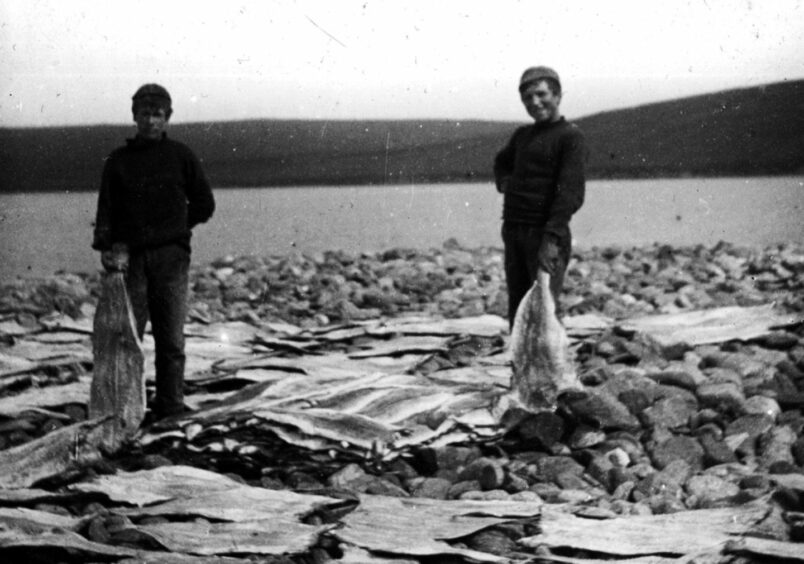

“Fish were salted and laid up on beaches in Shetland to dry.

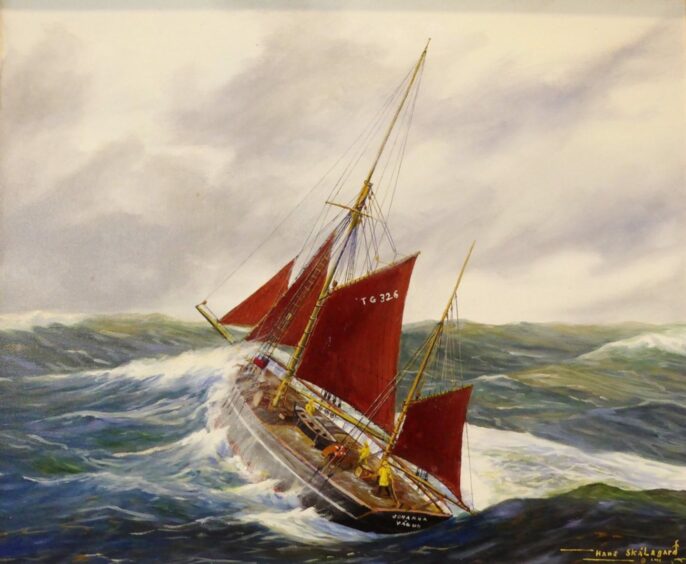

“In the 19th century there was a huge fleet of distant water vessels that began to fish around Faroe and Iceland and Greenland.

“About 100 of these vessels from Shetland employed more than 1000 fishermen –doing long trips, catching cod, salting them on board, taking them back, drying them on beaches.

“That was all then exported to Spain, especially to the Basque region where it was used as the main ingredient for Baccala – the famous Spanish and Portuguese cuisine which still exists today as a favourite in most Spanish restaurants.

“Shetlanders were catching the cod at Greenland and Iceland, taking them back, curing them on the beaches then exporting them. That lasted 100 years.”

Why was Shetland ‘pivotal’?

Far from being a remote island community on the fringes of the North Atlantic, Shetland was “really pivotal” to the huge trade in salt cod.

It was the arrival of the herring industry in the late 19th century, however, that “eclipsed” everything.

“It became enormous,” says John.

“Lerwick was described as the herring capital of Europe in 1905.

“And of course the herring were also salted, but they weren’t dried. They were salted and barrelled, and these barrels of salt herring were then exported to Baltic ports – St Petersburg, Stettin, Lubeck, Danzig, Hamburg.

“All of these Baltic ports then supplied these barrels of salt herring into Poland and Russia, very often to poor rural communities and the Jewish shtetels of Eastern Europe which were huge consumers of salt herring.

“It was said a barrel of salt herring from Shetland was very often the difference between surviving a bitter Siberian winter for some of these very poor rural Jewish communities.”

Between the Haaf open boats, the big cod schooners going north and the herring fleet exporting cod to Spain and then herring to the Baltic and Eastern Europe, Shetland was at the hub of this salt trade for 300 years.

Cultural influence

John called his book The Salt Roads in reference to the voyages that the boats went on to catch the fish with. The roads refer to the export routes.

The sub title of the book ‘How fish made a culture’ refers to the theme running through the book about how artists were inspired by this.

“I’ve got a chapter on Hugh MacDiarmid who spent eight years in Shetland and what he wrote about fishing in Shetland,” adds John.

“I’ve got a variety of musicians in my book. I deal with some of the famous Faroese painters who painted, I deal with Halldór Laxness the famous Icelandic novelist: the cultural social theme going through the book as well as the straightforward historical narrative.”

John said the book developed having enjoyed speaking to and hearing the stories of so many people as part of his research for the Cod Hunters.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, he found himself at home with plenty of time at hand to start working on The Salt Roads, which is published by Birlinn.

“I wouldn’t use the word nostalgia when describing the book,” says John.

“It’s looking back at the historical continuity. Fishing is still huge in Shetland, as is fish farming. It’s still the biggest industry on the island.

“It’s not looking back at an industry that’s gone.

“It’s not nostalgic in so far as there’s no rose tinted spectacles.

“It’s looking back at the highs and the lows, the tragedy both for companies and for individuals who lost their lives.

“The high points and all the cultural aspects associated with it.

“It’s not a history of how many boats, how many fish, that kind of thing.

“It’s really looking at this through the eyes of many individual people. Some contemporary people in Faroe and in Spain looking back, and some historical characters I’ve tried to bring to life in the historical narrative.”

Modern Shetland industry

Today, the Shetland seafood industry is worth over £300 million.

However, the statistic John says really “knocks peoples’ socks off” is the revelation that there’s more fish landed in Shetland than in England, Wales and Northern Ireland combined.

While it’s a very different industry to the historical one described throughout the book, it still remains very important economically and it still remains incredibly important socially and culturally.

John tries to tell the historical, social and cultural story through the eyes of individuals.

But at the end of the book he brings it right up to date by reflecting on where the industry is now, and where its future lies.

While Brexit has proved “very controversial” – some fishermen who backed Brexit now feel it didn’t deliver anything like they were promised – John feels the biggest threat comes from campaigning environmental organisations who take a “simplistic” view and would like to see fisheries shut down completely.

“It faces possibly the biggest challenge it’s ever faced in its history in the campaigns by some of the NGOs – in the campaigns by some of the more extreme environmental organisations – looking to shut down fish farms and looking to close fishing and huge sea areas,” he says.

“I take the book right up to date and say well actually if you are looking at the carbon footprint of producing fish as opposed to the carbon footprint of producing other types of food, fishing is actually part of the solution – it’s not the problem.

“It’s actually one of the ways of producing food around the planet that has the lowest carbon footprint.

“It’s a great way to create protein if we are all willing to do it in the most carbon friendly way.

“So it is an historical book but I do bring it right up to date.”

Research surprises

When it came to research, the ledger archives in Lerwick were invaluable.

The other information in the book is really what he’s gathered over a lifetime travelling around Europe to fishing communities.

But there were still many surprises along the way.

For example, on a trip to Faroe, he was having a beer in a village pub and got talking to the land lady who told him how her ancestors used to sell illicit brandy to the Shetlanders.

John was intrigued and thought he might have to go to Torshaven or even Copenhagan to see the records.

But it turned out they were in leather-bound archival books housed next door.

“The scale of the smuggling was far greater than I ever thought!” says John.

“I kind of thought it was bought for the Shetland fishermen’s own consumption.

“But clearly when these guys got back to Shetland, with the quantities they were buying they were conducting a nice little trade in selling on the brandy to the Shetlanders during the winter months.

“That was one example of an absolute surprise which stemmed from a chance encounter in a pub!”

John hopes to write a future book about the ongoing links in the north Atlantic between Iceland, Faroe, Shetland, Scotland and Norway.

Where to get the book

*The Salt Roads: How fish made a culture by John Goodlad is out now published by Birlinn, £17.99.

Conversation