The lost village of Muirton of Ardblair is the subject of an exhibition launching in Perth on October 8. Gayle Ritchie chats to curator Paul Adair.

A group of serious-looking children scrub around in the dirt playing boules outside a whitewashed thatched cottage.

Villager Isobel Chapel pumps water from a trough, Jane Gow sits reading a Bible. A horse stands tethered to a cart in a copse of trees.

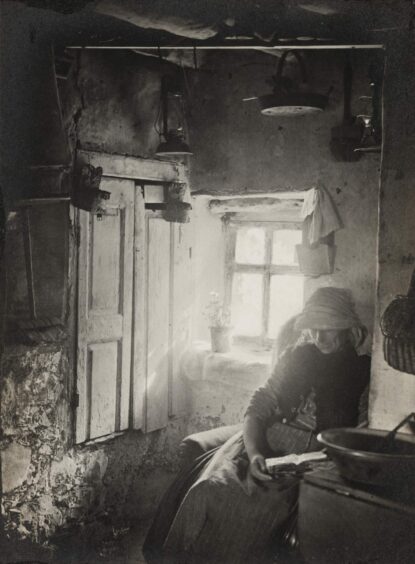

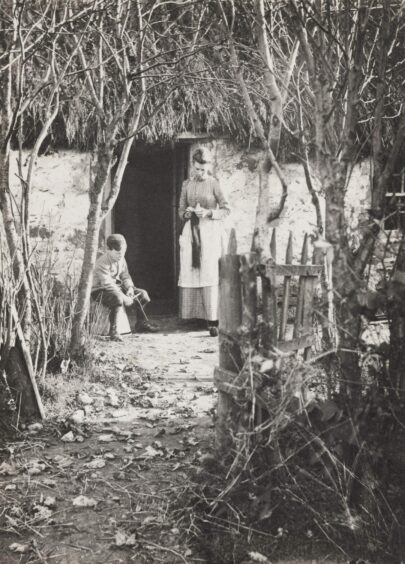

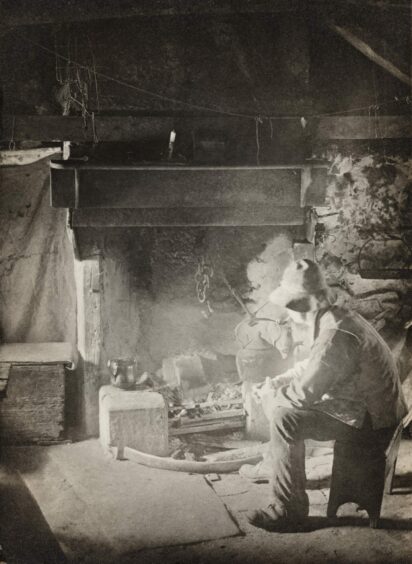

These are just some of the evocative scenes portrayed in a collection of rare photos taken at Muirton of Ardblair in 1893.

Once a small but thriving community on the outskirts of Blairgowrie, ‘The Muirton’, as it was known locally, grew as a township of flax spinners and tenant farmers living in ramshackle cottages.

Many were thatched, with earth floors and no running water.

Slow decline

With increasing industrialisation and the rise of water-powered mills, the village’s population declined after the First World War and the cottages fell into a slow decline.

The last remaining resident, Jenk Gow, passed away in 1972 – 50 years ago.

Sadly, almost nothing has been preserved of the village, which once boasted around 20 cottages.

Had it not been for artists and photographers who were drawn to its picturesque qualities, the community and its stories might have been completely forgotten.

New exhibition

However, this way of rural life is the subject of a new exhibition launching today at Perth Museum and Art Gallery.

Featuring rare photographic prints from 1893, historic artefacts, and paintings by Ewan Geddes, one of the local artists known as the ‘Blairgowrie Boys’, the exhibition runs until December 23.

Geddes, who was born in Blairgowrie in 1866 and died in 1936 aged 70, declared he had “found artistically all his soul longed for” in The Muirton.

Paul Adair, collections officer at Perth Museum and Gallery, took great joy in curating the new exhibition.

He believes the village had a “magical attraction” for artists and photographers.

“By the late 19th Century, Muirton of Ardblair was a township in decline. The population was aging, younger folk had left in pursuit of better prospects in the towns,” he says.

“Many of the cottages were in need of repair and some in the final stages of decay when the photos were taken.

“They began to look like they belonged in a bygone era.

“This very character gave it a reputation as a ‘Brigadoon’, a place that is idyllic, unaffected by time, or remote from reality. Its quaintness was attractive to artists.”

Annual photography excursion

In 1905, The Scottish Photographic Federation chose Blairgowrie for its annual excursion.

Around 60 photographers descended on The Muirton as part of the itinerary.

A report in Dundee’s Evening Telegraph the following day stated: “In the afternoon parties went, under the guidance of local photographers, to the Muirton of Ardblair.

“Horses and carts, children, and even the peace-loving pigs were pressed into the service. The crowd round the celebrated residence of Mr Brough was at times so great it was necessary to work in relays.”

Folio acquisition

The idea for the exhibition arose following the acquisition of a folio of rare 19th Century photos of the now-vanished village, although Paul says it’s not known who took them.

“They were carefully composed and constructed – they’re certainly not snapshots,” he reflects. “They’ve been created by someone with a very artistic eye.

“The queue to photograph the ‘famous’ Brough’s Cottage and its residents is intriguing.

“It’s interesting to consider what that attraction was and whether we over-romanticised what must have been quite a hard way of life.

“I think, even back then, it was seen as a traditional, rural way of life that was vanishing and people were drawn to that.

“The cottages are higgledy-piggledy random constructions. They’re very picturesque.”

Village descendants

After acquiring the photos of The Muirton, Paul contacted Jennifer Woods, a descendant of artist Ewan Geddes, and it turned out she had carried out a lot of research on the lost village herself.

He also got in touch with Gordon Greig, whose great aunt was Jenk Gow, who died in in the cottage known as The Neuk.

“Gordon gave me loads of personal recollection of his visits to The Muirton as a boy, playing there, and about the characters who lived there,” says Paul.

“I interviewed him on site and he talked about where Brough’s cottage was, where the heart of the clachan was, and so on.”

Both Jennifer and Gordon contributed to a book published in 2017 by Margaret Laing titled Muirton of Ardblair: The Lost Village and the Artists Who Keep the Memory Alive.

This had a limited run and was only available in the local newsagent’s shop.

But, says Paul, it was a great resource upon which he drew when creating the exhibition.

Mix of artefacts

As well as photographs, it boasts a mix of historic artefacts, including household objects like soup terrines, spinning wheels and agricultural objects.

While they don’t have a high monetary value, Paul believes they’re “very relatable” to people and reflect a lost way of life.

“They serve an obvious function that we can recognise today,” he says. “They represent the basics of life.

“We’re showing the original photos framed in one part of the museum and in another space we’ve digitised these to a high resolution so they occupy a full wall. It will almost be like entering into the space.”

Flax industry

Paul says the origins of The Muirton are likely linked to the growing of flax, a crop whose fibrous stalks were turned into linen.

“By the mid-19th Century it supported a community of about 20 flax spinners and linen weavers living in cottages with earth floors and thatched roofs,” he says.

“This cottage industry gradually died out as the water-powered mills of Blairgowrie and Coupar Angus became dominant.

“The census of 1861 records 11 handloom weavers in The Muirton, but by 1871 there were none.

“Despite this, The Muirton continued as a community well into the 20th Century. The occupants maintained small strips of land called ‘riggs’ where flax, potatoes, turnips, grass, barley, and oats were grown.”

But and Ben

The cottages of Muirton of Ardblair were mostly simple two-room residences known as ‘but and bens’- the ‘but’ being the kitchen and entrance, which gave access to the adjoining ‘ben’.

Their walls were constructed of locally found stone and rubble held together with earth and clay.

The roof was timber thatched with rushes which grew plentifully in the surrounding boggy land and around the nearby lochs.

“It’s interesting to consider what that attraction was and whether we over-romanticised what must have been quite a hard way of life.”

PAUL ADAIR

The floor was compacted clay. Sometimes the interior walls were lined with old newspapers pasted on to the walls for insulation and draft proofing.

Cooking would have been over the open fire using a ‘swey’ or ‘swee’ to suspend the pot or to heat water in a kettle.

Fuel would have been bundles of wood collected locally and peat where available.

Water was hand- pumped from an underground burn into a large communal wooden barrel then carried in a bucket to the house.

Box beds, enclosed by timber sides and ceilings, gave a little privacy and warmth.

Some would have had doors to close them from view during the day as the bedroom also served as kitchen and living room.

A weaving community

In the early 18th Century, flax growing was encouraged to boost the economy of rural Scotland and between 1727 and 1748, the amount grown in Scotland trebled.

Around this time at Muirton of Ardblair, flax was spun during the winter months and ‘rents were paid from the yarn’.

There were many marshy areas around the Muirton and lying pools of water that were ideal for ‘retting’ – the process of soaking the flax to ferment and help separate the fibres.

In the mid-1800s, handloom linen weaving was recorded as being the occupation of almost all the heads of the households, but by the end of the century, the role of linen as a cottage industry was over as the power mills of Blairgowrie and Coupar Angus took over.

The landowner, the Laird of Ardblair, gave tenants more land to cultivate for other crops and employment gradually diversified.

- A Lost Community: Muirton of Ardblair is open October 8 to December 23 at Perth Museum & Art Gallery. Entry is free but donations are welcome.

- The photos were purchased by Culture Perth and Kinross thanks to funding from the National Fund for Acquisitions, administered with Scottish Government funding by National Museums Scotland.

- A series of craft activities are being organised around the exhibition including talks and workshops for children. For details see culturepk.org.uk/whats-on/a-lost-community-muirton-of-ardblair/

Conversation