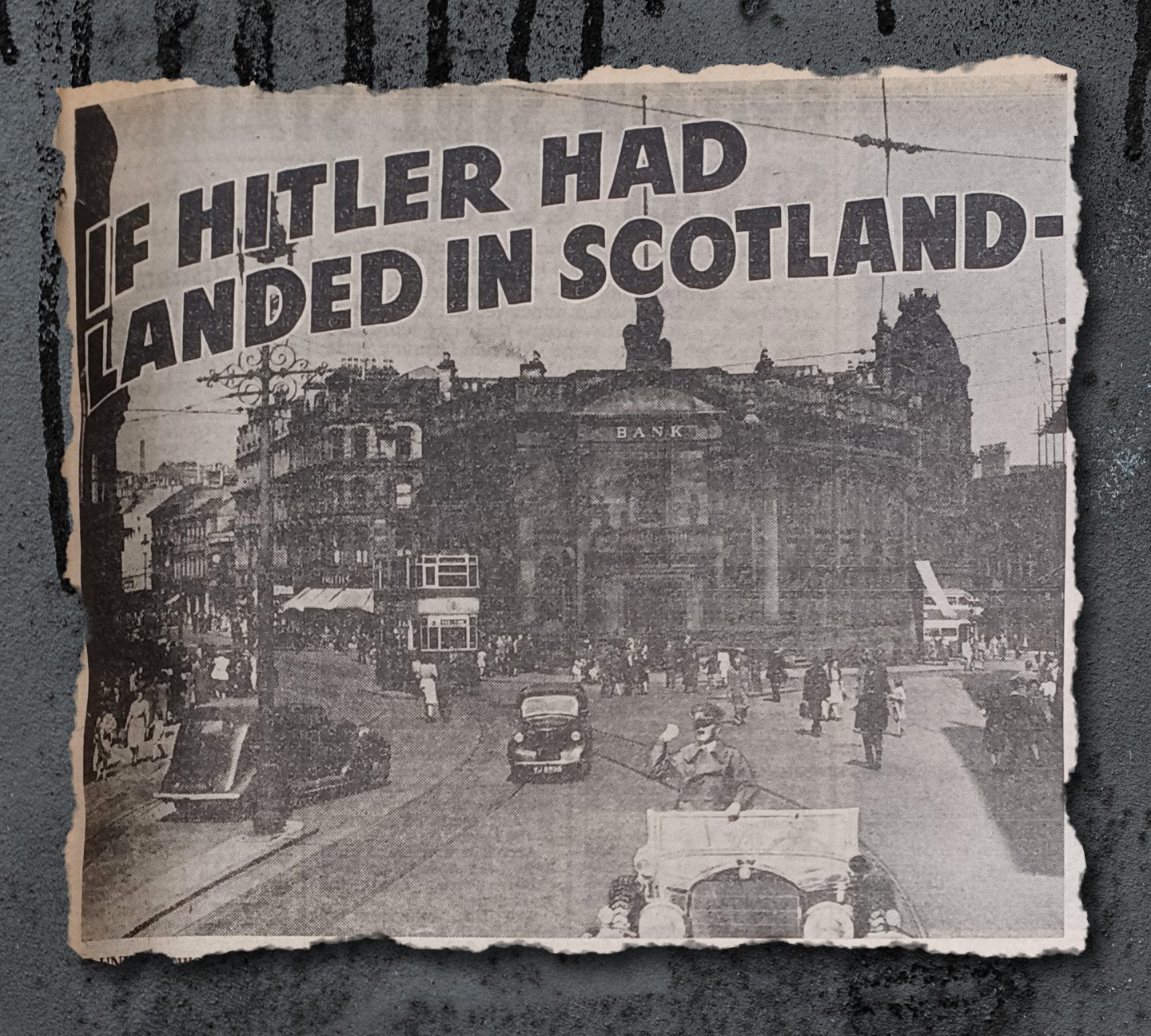

A highly-secret military unit was scrambled during World War Two to carry out a last-ditch defence of Fife as Adolf Hitler’s Nazis prepared to pour across the channel.

The 10-man guerrilla warfare brigade were set up to take the fight to Nazi Germany if Hitler’s Operation Sea Lion was ever given the green light.

The Fife branch of Winston Churchill’s so-called secret army was made public decades after the guns fell silent in a forgotten interview by Robert Edward Cathcart in 1970.

Cathcart was enrolled in St Monans as the leader of the auxiliary unit in 1940 and told his story to the Evening Telegraph 30 years after signing the Official Secrets Act.

Cathcart said: “Dunkirk was only a week old and the British people knew they had their backs to the wall as Hitler’s hordes prepared to pour across the channel.

“Like any other old soldier of World War One, I realised we had taken a licking and that even the magnificent spirit of Dunkirk could not replace armies lost in Belgium and France.

“These thoughts were in my mind that Wednesday morning as I went from St Monans to Anstruther to do some business at the National Bank in the High Street.

“As I left the building, I became aware that someone was staring at me hard and thoughtfully.

“I gazed back at him with keen interest, for in Anstruther a stranger is easily spotted.

“This man, in the uniform of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, looked as if he had stepped out of a shop window.

“Then the immaculately clothed figure crossed the road towards me.

“He introduced himself as the Captain Eustace Maxwell.

“Captain Maxwell then asked me if I had been in the First World War.

“I told him I had been in France as a lad of 17 with the Royal Garrison Artillery and had been gassed twice.

“This stranger had charm and personality and I found him easy to chat to, but I wondered suspiciously how he knew so much about me.

“Then he came abruptly to the point.

“He asked if I would like to do a special duty during the war.

“Everybody wants to do something special.

“But I wanted to know what he wanted me to do.”

Churchill’s secret army

Captain Maxwell told him the work concerned “a secret organisation just in its infancy”.

Cathcart said: “Very few knew anything about it.

“In the event of the Germans over running the country, and this seemed very likely that summer day, the movement he was speaking about would go to ground.”

This was, of course, an auxiliary unit, sometimes known as “Churchill’s secret army”.

The auxiliary units were specially-trained, highly-secret quasi military units created by the British government during the Second World War.

They would act as a line of internal defence following the expected invasion of the UK by Nazi Germany which was given the codename of Operation Sea Lion.

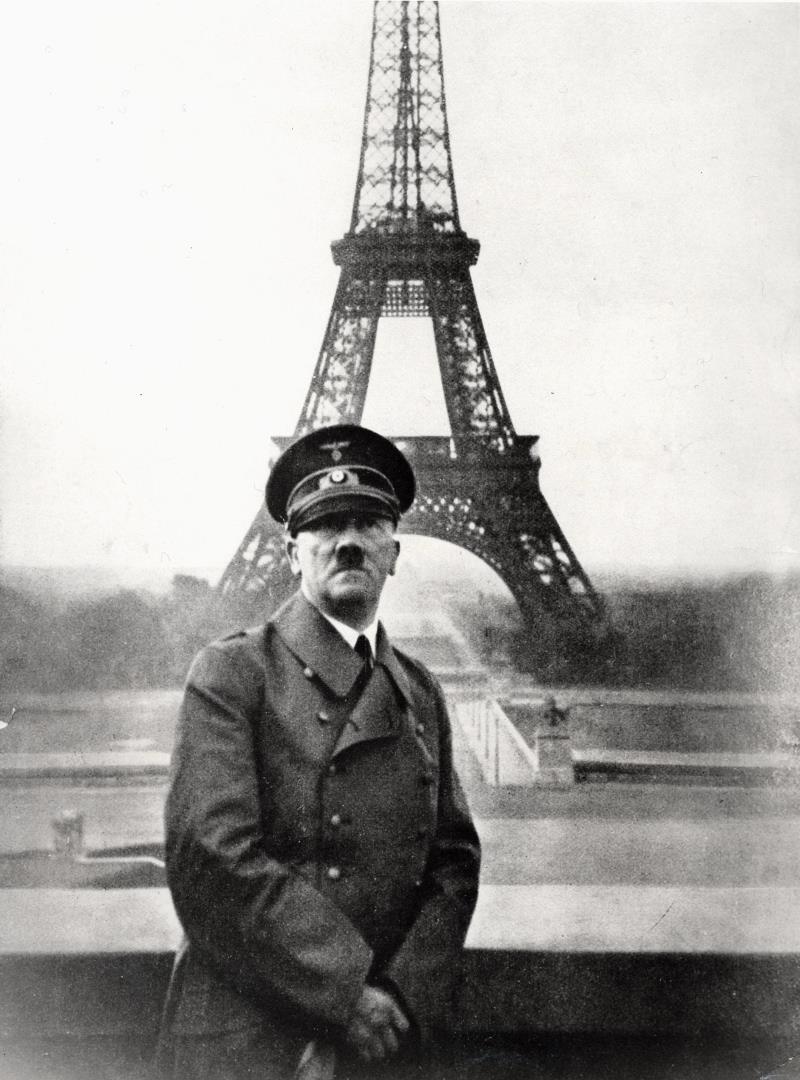

Hitler believed that Operation Sea Lion would have led to the rapid conclusion of the war after setting in motion preparations for a landing on July 16 1940.

Operation Sea Lion

He prefaced the order by stating: “The aim of this operation is to eliminate the English Motherland as a base from which the war against Germany can be continued, and, if necessary, to occupy the country completely.”

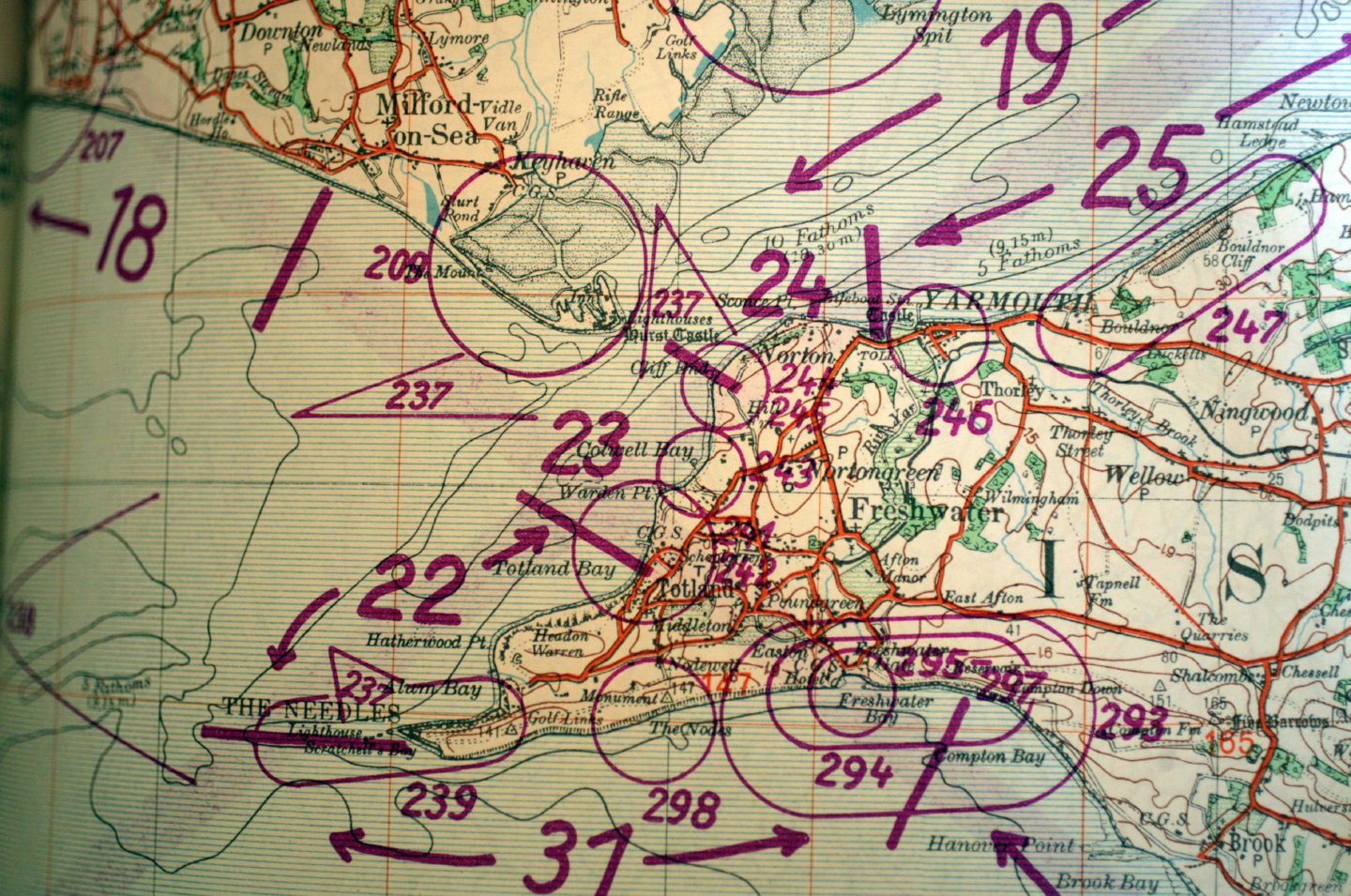

Hitler’s directive set four conditions for the invasion to occur.

The RAF was to be “beaten down in its morale and can no longer display any appreciable aggressive force in opposition to the German crossing”.

The English Channel was to be swept of British mines at the crossing points.

The Strait of Dover had to be blocked at both ends by German mines and the coastal zone between occupied France and England “dominated by heavy artillery”.

Cathcart said: “My mind was made up; I was in.”

From Anstruther, Cathcart and Captain Maxwell drove to a deserted spot on the Cupar-Crail road and reached Airdrie woods.

Cathcart added: “There he showed me a detonator, a stick of gelignite and different kinds of uses for detonating the explosives.

“Then, in the lonely Fife wood, I leaned against a tree and signed the Official Secrets document.

“I was now enrolled as a member of the Scottish resistance movement.”

Speaking in 1970, Cathcart continued: “It all seems cloak and dagger stuff now, almost James Bond-ish – but back in 1940, it was grim reality.

“Britain was fighting for time to regroup her forces and had there been an invasion, we would have been in a desperate plight.”

The haste with which the resistance movement was being organised speaks for itself.

Cathcart saw Captain Maxwell on the Wednesday, and by the Thursday of the following week, he was at the British headquarters of the movement, at Coleshill House, eight miles north-east of Swindon.

There, him and the rest of the recruits, were instructed in the use of firearms and plastic explosives, as well as more traditional weapons.

Then he was told to return home and set up his secret unit.

Back to St Monans

Cathcart said: “Back in St Monans, I approached different men I knew and put the proposition to them.

“Without hesitation they accepted, and we had our own codename – Operation Cromwell.

“Within days we were building our underground base.

“All the work has to be done at night or in our spare time at the weekends.

“It’s not easy in a place the size of St Monans, with a population of 2,000, to keep a secret like that.”

But he did.

Their first base was located on Balcaskie Estate in Pittenweem.

Near an old chapel and 12-feet underground, a zigzag tunnel led into the base, which also had an emergency exit at a nearby barn.

The main entry to the shelter was the root of an old beech tree which Cathcart and his men hinged up as a doorway.

Cathcart said: “By this time I had the rank of Lieutenant, and my second in command was a Mr Pratt from West End, St Monans.

“Our other unit members included Lieutenant Crowe, from St Andrews, and Bob Wilson from St Monans.

“These men were the nucleus of the 10 man force I needed to make the base operational.

“A grand bunch of men, and keen as mustard.

“No commanding officer could look for better.”

Fearing discovery

Cathcart continued: “All these clandestine activities were bound to intrigue our wives but none of them ever inquired as to what we were even up to.

“To all appearances, we were members of the Home Guard.

“The only time we feared discovery was when an old lady – who was housekeeper at Balcaskie House and liked to walk in the woods every night – became interested in what we were doing.

“I told her we had been instructed to dig the foundation for a big gun, but as a builder, I knew the foundation wasn’t strong enough and the ground would be restored to his old appearance within a week or two.

“She accepted this explanation and went happily on her way.”

They may have been left in peace, but the base’s problems were just beginning.

“I told my men that during the day, especially when going round farms, they should keep their eyes open for any material that would go into the building.

“We had to work this way because as an auxiliary unit at this stage we had no organisation for indenting for the supplies we required through normal military channels.

“My men took me at my word.

“At night, they crept in darkness into farm yards and stealthily removed corrugated iron sheeting.

“The farmers weren’t the only ones to suffer.

Secret messages

“We had other civilians working for the organisation.

“Their job in the event of invasion was to go about their normal work as usual, but to keep their eyes and ears open as to movements and installation of enemy units.

“Anything they heard of military importance was to be passed on.

“A post-box was set up under a pre-selected loose stone on a lonely stretch of road.

“The messages would be left there and we would send someone each night to collect the mail.”

This post-box arrangement also helped Cathcart’s base keep in touch with other units.

Within two weeks, the St Monans base was operational.

It was the first of its kind in Scotland and Cathcart said it was “so well camouflaged that no one would have known we had worked there”.

He said: “Many people passed our tree door entrance – but none spotted it.

“Now all we had to do was wait.”

The waiting game started in earnest.

Cathcart said: “In September, the signal we awaited came through.

“The might of the German forces seemed to be on the move.”

The German Army and Navy had sent a large number of river barges and transport ships to the Channel coast.

Cathcart added: “It only needed the final word for what we know now was termed Operation Sea Lion to swing into action and the invasion of Britain to begin.

“So the message was flushed to Scotland for all auxiliary units like my own to go to ground.

“We sat in our hideout wondering not only what the next few hours but the next few weeks would bring.

“We had iron rations for four weeks if necessary.

“We played cards but no one’s heart was in the game.

“Time ticked by with margining small slowness.

“Then after hours of waiting we received word that the alert was over.”

Hitler’s Operation Sea Lion depended on the British home squadrons being damaged or destroyed by air and torpedo attacks.

The Luftwaffe’s failure to achieve air supremacy in the Battle of Britain forced Hitler to postpone Operation Sea Lion indefinitely on September 17 1940.

Thankfully Fife’s ‘secret army’ resistance movement never saw action but their dogged determination to defend the kingdom at all costs remains hugely inspiring.

Conversation