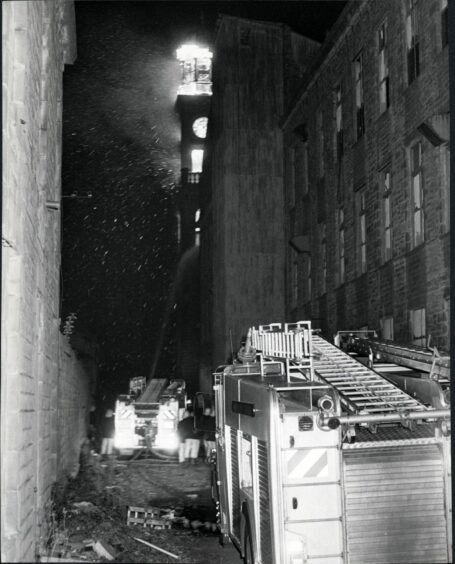

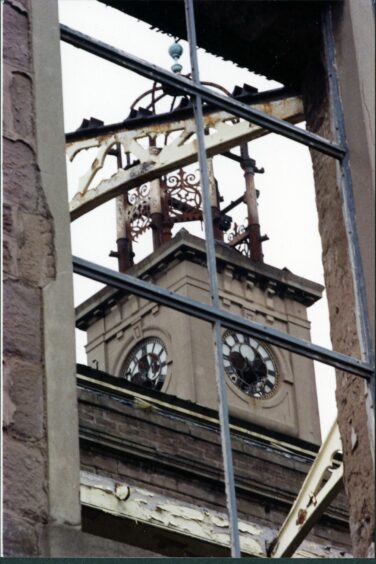

Time stood still when the famous clock tower at Camperdown Works was devastated by fire in 1987.

An intense blaze damaged the High Mill including the ornate 100-foot tower and fears were that the centrepiece of the once-grand jute works would be razed to the ground.

Word of what was happening spread around Lochee almost as quickly as the inferno which took hold at the A-listed building on September 7 1987.

Timbers reportedly “the size of train carriages” rained down from the crumbling structure as firefighters fought desperately to bring the blaze under control.

Once the flames died away the question was whether the clock tower could be saved?

Its future was hanging in the balance 35 years ago in October 1987.

So what happened?

The Camperdown Clock Tower

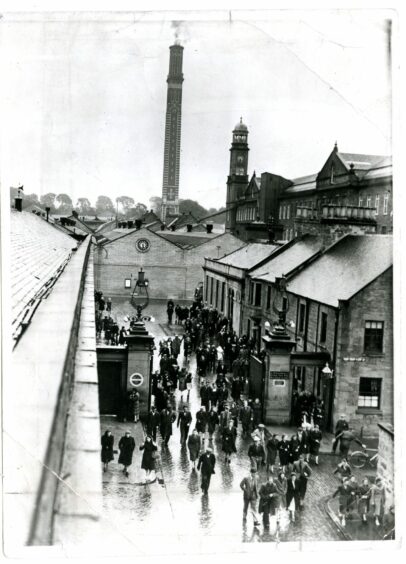

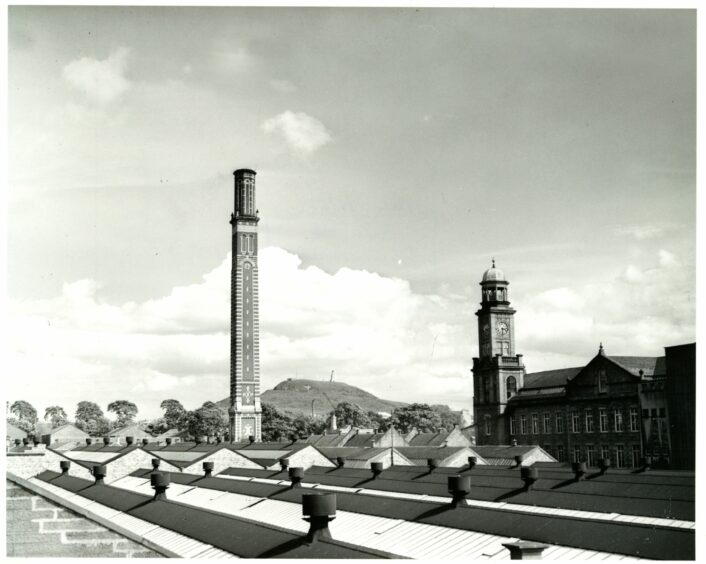

At its height, the jute industry employed over 40% of the able workforce in Dundee.

Camperdown Works was the largest in Europe, boasting 820 power looms, 150 hand looms and more than 5,000 workers.

The clock tower and high clock was built in the 1860s and stood alongside the 282-foot Cox’s Stack which became a landmark for Dundee’s Irish quarter.

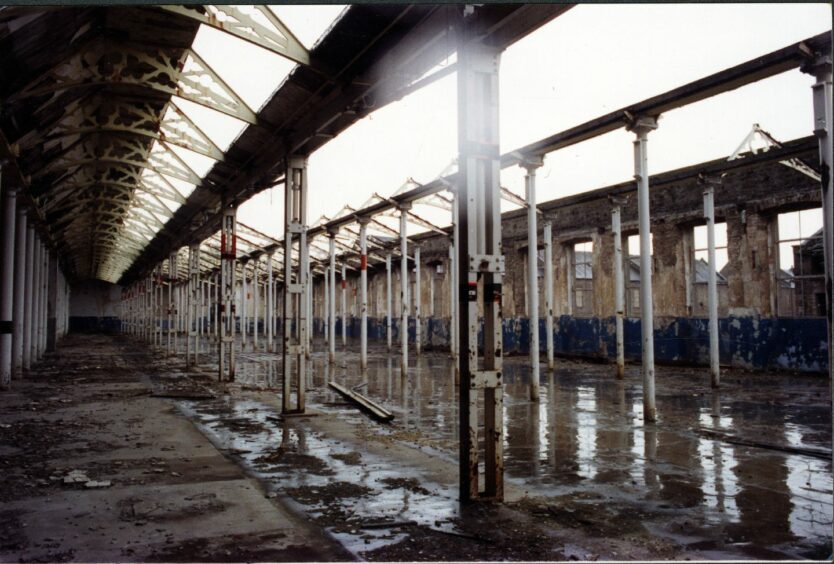

The works closed in 1981 when markets slumped to an all-time low and over the next few years the buildings were abandoned and fell into a decayed state.

On the night of September 7 1987, the elaborately-decorated clock tower was transformed into a massive pillar of fire which was visible for miles around the city.

The flames spread quickly through the High Mill and soon reached the cast-iron and copper roof of the derelict building.

At around 9.30pm emergency services from across the city were called to tackle the blaze and they were faced with difficulties from the outset.

People from Lochee turned out in their hundreds to watch the drama unfold.

Access to the tower was only available via a small ramp, or through a narrow alleyway.

Most of the ground was obstructed by the time the emergency services arrived, covered in piles of fallen rubble.

Additionally, the lack of an internal staircase meant that firefighters were unable to fight the fire from within.

The blaze itself was the most difficult obstacle, however, and was so intense that by 10pm the firefighters had to change tactics.

Fire chiefs removed their ladders from against the tower as the heat from the blaze became too harsh to bear.

Instead, they chose to fight the blaze from the ground up, using ground monitors to keep a steady flow of water on the outbreak.

Dodging timbers the size of train carriages and showers of orange and golden sparks, fears that the Hugh Mill roof would collapse onto them saw the firefighters divert their attentions for a second time.

Turning to the buildings adjacent to the tower, the roofs were doused in thousands of gallons of water in an attempt to prevent further spread of the fire.

Deputy fire-master Sam Marshall said at the time: “We had to use our discretion in this situation.

“There were no lives at risk in this situation.

“There was therefore no point in risking the lives of our own men just for the building’s sake.”

However, at 11pm the firefighters used a turntable ladder to douse the flames as the fire started to move through the main factory building.

This was the turning of the tide.

The spread of the fire was finally prevented from escalating further and started to fade.

By 11.30pm, the blaze had been extinguished, but thick billows of black smoke continued to emerge from the windows of the tower as a reminder of the ferocity of the flames.

Camperdown Works fire a ‘tragedy’

Lochee councillor Charles Farquhar described the event as a “tragedy”.

At the time, he said: “It is devastating to see the place reduced to nothing more than a bomb site.”

Mr Kevin Donnelly, the SNP secretary for Dundee West, added: “It is a monumental destruction of local heritage.”

Investigations begin

Investigations into the fire’s cause began immediately.

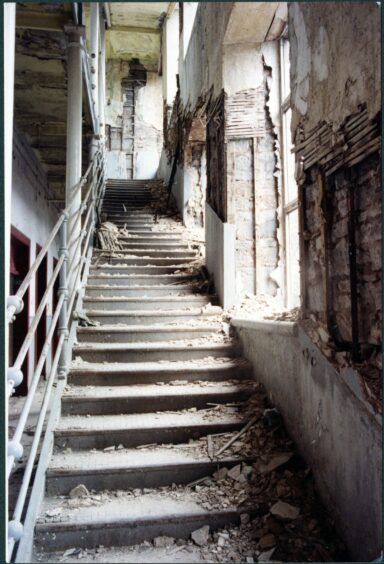

Police believed vandals were responsible for the blaze, which had caused the iconic tower to be earmarked for demolition such was the extent of the damage.

Further investigations discovered that the fire was started in the third level of the building, and that all combustible materials had been destroyed, leaving the structure vulnerable to high winds.

A stone lintel was badly cracked, and one of the eight cast iron columns that supported the top octagonal tower was also badly damaged.

Two further cast iron bars were missing.

The council’s chief engineer, James Hutcheon, declared the clock tower was unsafe from the third-storey upwards.

The owners of the building would now be responsible for securing the property and the entire site.

Councillor Tom McDonald was concerned about what the blaze would mean for the site’s upcoming plans.

The ironically named Flame Lodge Ltd had purchased the site earlier in the year with the intention of turning it into a housing development.

At the time, Mr McDonald said: “The plans for the area were to be predominately housing, with the clock tower acting as one of the main features.

“It’s a sad day for Lochee with one of our major landmarks lost.”

Despite the damage done, it was hoped by the council that the most outstanding feature of the tower could still be saved.

The roof of the clock tower had remained intact owing to its strong structure.

Mr Hutcheon began new examinations on the site to see if the tower could be saved in December 1987.

His review ended with placing an order to the district building control committee to make the tower safe.

The order was granted.

Repairs would be made to the clock tower, and offers were invited from contractors for remedial work.

The Camperdown Redevelopment Project

After the tower was secured, work began on the Camperdown housing development in 1991.

The houses would be developed by Servite Housing Association for elderly and disabled people.

With funding support from Scottish Homes, a total of 83 flats were built at the site.

The housing development was part of the greater Camperdown Works regeneration programme, which included the building and development of the Stack Leisure Park.

Alongside Cox’s Stack, the clock tower remains at the Stack Leisure Park today, although its clock mechanism and the bell are now missing.

They stand as survivors of the original jute works and the city’s history.

Conversation