Preconceptions about the Antarctic and commercial whaling are challenged in a new book. Michael Alexander speaks to the author about the parallels of environmental and human exploitation by capitalism today.

When former academic Sandy Winterbottom embarked on an epic six-week tall-ship voyage from Uruguay to Antarctica in 2016, her pristine image of the Antarctic was shattered when she discovered the dark legacy of 20th century industrial-scale whaling.

Arriving at their midway stop in South Georgia, she was shocked to discover that former whaling stations had been abandoned in the world’s most pristine environment with apparently no attempt to clean them up.

Asbestos and wreckage littered the shores, and on the beaches, thousands of discarded whale bones demonstrated the “mind blowing” scale of the industry and the estimated two million whales taken in the Antarctic Ocean alone.

Angered by what she found, the environmental scientist with a lifelong aversion to commercial whaling, was quick to blame the men who undertook this wholesale slaughter.

Discovery of graves

But when she stumbled across the grave of an 18-year-old whaler from Edinburgh, alongside those of other ‘local’ working men from Scotland, she began to think about the human side of whaling and how these crewmen could have died so far from home.

She began to explore the legacy of commercial whaling in terms of colonialism, capitalism and its link to environmental and human exploitation.

“One of the things that really sparked my interest to do more research was when we were at Leith Harbour Whaling Station on South Georgia,” explains Sandy, who lives near Muckhart in central Scotland.

“We came across a small graveyard. There were the graves of men from Alloa, down the road from me, men from Edinburgh.

“That brought home to me how local whaling was to Scotland.

“But it was when we came across the grave of an 18 year old young lad Anthony Ford from Edinburgh – it said 19 on his gravestone – who was a whaler there and who died.

“He was about the same age as my son. I just asked the question: ‘oh my goodness, what is a young man of that age doing half way across the world?

“How did he end up here? What happened?’

“That was my starting point that led me into the human side of whaling.”

Authentic account

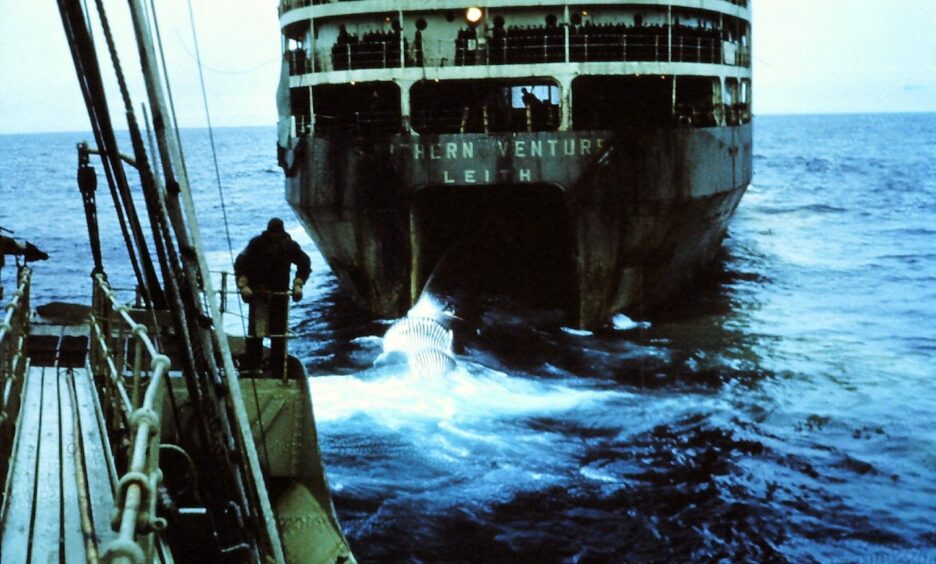

Anthony Ford left no written accounts of his journey. Born in Granton in north Edinburgh in 1933, he applied aged 15 at the Salveson office in Edinburgh for the post of mess-boy aboard factory ship Southern Venturer, which sailed from Newcastle in 1948.

Less than four years later he found himself stuck in the “stench and filth” of South Georgia where he died in 1952 aged 18.5.

While many details of his life were lacking, a “scaffold of fact” could be constructed from the stories of other whalers who gave an insight into the “typical” experiences he would have had.

Sandy also managed to make contact with his extended family who filled in some of the gaps.

One of the things she discovered was that during the post-Second World War years, the gruelling work was a way for the whaler men to try and lift them and their families out of poverty. But it came at a price.

“It’s a true story in the sense of it’s an authentic account of what a young lad’s experiences would have been,” she says, “and how that impacted him and his mental health.

“I think his experience was really quite typical.

“Circumstances around his death were linked in to the blasé attitude by the whaling company owners towards the men’ safety and the men’s welfare and wellbeing.

“Really there was no health and safety, there were no unions, there was nothing to protect these men and mostly boys – the lads went whaling at 14 or 15 years old which is when Anthony started whaling.”

Debut book

In her debut book The Two-headed Whale, Sandy brings to life the spectacular scenery and wildlife of the vast Southern Ocean, set alongside the true story of Anthony Ford as he sailed the same seas and toiled in an industry where profits outranked human life.

The title is a metaphor inspired by a picture a whaler sent her of a conjoined whale foetus, cut from a pregnant mother they should never have killed.

But while the book’s focus is on the historic commercial whaling industry and humans’ troubled relationship with the planet, Sandy sees the legacy of colonialism, capitalism, environmental and human exploitation as being “wholly relevant” to what’s going on in the world today.

“It’s easy to talk about whaling from merely an environmental point of view,” she says.

“But I don’t think in any environmental problem we can disentangle the human element.

“There are so many parallels between the whaling industry and the fossil fuel industry, the oil industry.

“Effectively it’s about the kind of industrial scale exploitation – not just to our environment but to our people – and that’s still going on.

“We’re seeing that with trade unions today, we’re seeing that with the rise of strike action.

“Effectively, this kind of consumer based capitalism that’s being driven by the wealthy is driving so much destruction of the environment but also driving peoples’ misery.

“We’re in an absolute mental health crisis in this day and age because people are being driven to work faster, longer hours. The exploitation by the wealthy is still there.

“If we look at the people who made money off the back of the whaling industry, that money that was all made by these men and boys is still in the hands of the capitalists who were the owners.

“My message is this wholescale kind of exploitation of the environment, of people, by this consumer-based capitalist society is not serving us. It never has and it never will!

“It’s all about this consumer neo-liberalism that has been pushed upon us, that is destroying our environment and making us all utterly miserable in the process.”

Environmental background

Growing up in the south of England outside Reading, Sandy always felt a connection to nature, bolstered by idyllic childhood days “wandering in the woods”.

When she was 15, her parents moved the family to the Jurassic Coast on the south coast which fuelled her interest in fossils and rocks.

Studying geology at Southampton University, and learning about the dangers of climate change as far back as the 1970s, she went on to teach environmental science for the best part of 20 years at Stirling University.

In 2010, with a “fried brain having been in academia too long”, she took voluntary redundancy and ended up working in the renewables industry. But she also retrained as a remedial massage therapist.

Returning from that life-changing trip to South Georgia in 2016, she completed the creative writing masters programme at Stirling University.

But when Covid-19 forced her Stirling massage therapy clinic to close for the best part of a year, it also gave her the opportunity to write her book.

Love of sailing

Sandy has her step-dad to thank for her love of sailing. He taught her how to sail and she started doing tall ship voyages around 20 years ago.

She’s always loved the slower pace of the tall ship sailing community which are very much about being with nature and being “at sea”.

But she’s also always been fascinated by the Antarctic.

Inspired by Shackleton’s story and watching programmes like Whale Wars or reading Moby Dick, when the opportunity arose to go to the Antarctic as a paying guest crew member on a tall ship, it seemed “perfect”.

But only then did she realise how ingrained whaling was in Scotland’s history.

From the Dundee whalers that went up to the Arctic, right through to the industrial scale whaling in the Antarctic by the Salveson company based in Leith, she had little idea of its “dark legacy”.

“It’s not something that’s really talked about,” adds Sandy, who also founded an organisation called Women’s Climate Action which, amongst other things, campaigns against banks that are investing massive amounts of money in new fossil fuels.

“It’s a very covered up and hidden history in Scotland. There was also the whaling industry in the Western Isles and the basking shark industry.

“It’s really kind of woven right through Scottish history and a lot of the industrial wealth was built on the back of whaling, particularly in Dundee.

“But it was also a very brutal industry with a very dark legacy.

“I think we really need to take it out and examine it and look at what was good and bad about it.

“Because one of the things I discovered was that in post war times whaling was an opportunity for a lot of young men to bring themselves and their families out of poverty.

“In that respect there was a good thing that came out of it, but at the expense of the environment and the whales.

“In writing the book I also became much more aware how we are not going to solve the climate crisis without solving capitalism. I did end up radicalising myself, but out of necessity!”

Where to get the book

*The Two-headed Whale: Life and Loss in the Deepest Oceans by Sandy Winterbottom is out now, published by Birlinn, £14.99.

Conversation