From fears that the dead could return as ‘zombies’ to the Christian belief in the afterlife, Fife and Dundee archaeologist Douglas Speirs speaks to Michael Alexander this Halloween about historic interpretations of death and why death rituals are relevant to us all.

It’s that one night of the year when spirits were traditionally believed to walk amongst the living.

Today, the commercial manifestation of Halloween – also known as Hallows Eve, or the night before All Saints Day – sees the young traditionally dressing up in ghoulish costumes, dooking for apples – and guising.

But for the curious, it’s also a time of year that encourages thoughts about death and the afterlife.

More specifically, it can spark an interest in the past treatment of the dead and why specific burial practices are carried out.

Historic interpretations of death

One man with a keen interest in historic mortuary practices and how they provide informative windows into interpretations of death, resurrection and the undead, is Fife County and Dundee City archaeologist Douglas Speirs.

Given that the dead don’t bury themselves, acts of burial result from a complex suite of choices made by the living.

These choices reflect much about the way in which people of the past saw themselves and saw the world around them.

“Exactly what beliefs drove the bizarre nature of some of the earliest burial traditions will probably never be known,” says Mr Speirs.

“Why, for example, skull cults were a feature of so many European Mesolithic and Near Eastern Neolithic cultures is not known, yet the burial of ‘nests’ of skulls was a common activity across Europe 8,000 years ago.

“What is clear, is that the treatment of the dead has always held a spellbinding interest for the living.

“It’s this irresistible fascination that fuels the ritual we call burial.

“And it is a ritual. There’s no past approach to the treatment of the dead that was purely about the functional disposal of a corpse.

“True, rituals that include dead human bodies are not essentially different from rituals that use any other object.

“But more than any other ritual act, burial was – and still is – an intensely potent ritual activity.”

Death rituals – relevant to all!

Mr Speirs says the reason for this is because the ritual act is so uniquely relevant to us all.

Everyone is going to die and no one really knows what lies in store after death!

The only certainty is that one day, everyone will be centre stage in a death ritual whether that be burial or some other ceremony.

The challenge for the archaeologist trying to uncover past beliefs is to excavate burial sites as if a detective, looking for clues at a crime scene.

The aim is to find evidence that reveals just exactly how people in the past interacted with the bodies of the dead – what exactly they did with them before, during and after the ritual act of burial.

This then helps to answer the key questions in mortuary archaeology:

Why did they treat the body in this way?

What did they think or believe about themselves, about the world around them and about the world to come?

Concept of an afterlife

The significance of this is that every society at every stage of the human past has had some concept of an afterlife.

If they didn’t, they wouldn’t have ritually buried their dead, and there wouldn’t be any burials for archaeologists to find and excavate.

Nor would we see such a highly developed past interest in revenance – the return of the dead from death.

“Revenance, from the old French verb, revenir, ‘to come back’ – after death – is not a word we hear too often, unless you’ve seen Leonardo DiCaprio’s film, The Revenant!” says Mr Speirs.

“But we see belief in the concept everywhere in the historic burial record.

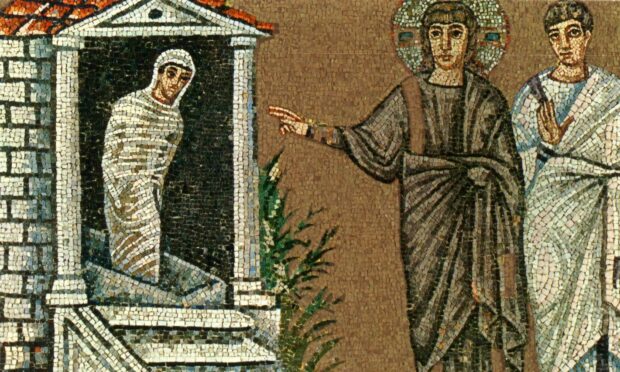

“The most famous revenant was of course Jesus, who three days after his death and burial near the site of his crucifixion on Calvary Hill – the Roman form of the Aramaic, Golgotha, ‘the place of the skulls’ – was observed to have conquered death, and to the astonishment of his friends and family, to have risen from the grave.

“Of course, the Christians weren’t the first to espouse a belief in post-mortem, whole-body resurrection.

“For a good 2,500 years before Christ, the Egyptians had been mummifying their pharaohs in the full expectation that they’d enjoy whole body resurrection in the afterlife.

“But the story of Lazarus of Bethany, and how Jesus restored him to life after death, has won for Christianity a pre-eminent place in world religions offering life after death.”

Significance of Cupar Muir cross-slab

Mr Speirs said Jesus spoke of the deceased Lazarus as sleeping.

This, he says, probably explains the recently found Cupar Muir cross-slab in Fife.

This little stone, found in a field at Cupar Muir, near Cupar, in 2015, has all the appearance of a typical 9th/10th century Celtic grave slab.

But its diminutive size suggests that it was more probably a very rare pillow stone – the ‘pillow’ upon which the head of the deceased was laid when in the grave.

Of course, those who buried this individual some 1,100 years ago would also have known the story of Lazarus.

They would have believed resolutely that on the Day of Judgement, when Christ returns to sit in Judgement, the deceased will physically rise up in his grave, will face Jerusalem, and will be judged.

It’s why Christian graves are orientated on an east-west alignment and it’s why the idea of death being a prolonged state of sleep was such a popular belief in the medieval period.

In a similar vein, the unusual treatment of “skeleton 155” – an unknown medieval male of 13th century date excavated in 1996 at St Ethernan’s Priory on the Isle of May, off the East Neuk – also reflects something of this individual’s hopes for the afterlife.

Originally thought to symbolise a devotion to St James of Compostella, the scallop shell and sheep bone placed in the individual’s mouth more probably symbolises the Eucharist and the deceased’s hope of resurrection in the afterlife – the shell being symbolic of the bread, and the bone, representing the transubstantiated Lamb of God.

These symbols recall the Last Supper when Christ instructed his disciples to break and eat bread as a symbol of his body.

Grave of Lilias Adie

“If the Christian dead could expect resurrection, it was hardly unreasonable for those in 17th and 18th century Scotland to believe that in extreme cases, agents of evil might also be capable of resurrection,” says Mr Speirs.

“That’s what the archaeology of a lonely burial in the inter-tidal muds in Torryburn Bay in west Fife tells us.

“The grave of Lilias Adie, a vulnerable, elderly woman who died during interrogation as a suspected witch on August 31, 1704, is a site of national archaeological interest.

“It’s Scotland’s only known revenant burial and the sad story behind this grave shines a unique light on the quite astonishing belief in revenance in early 18th century Scotland.

“Forced to confess to witchcraft, the minutes of Lilias’ interrogation record that she’d renounced her Christian baptism and become an agent of Satan.”

Christian baptism is seen, in essence, as being a “spiritual inoculation against evil”.

Without it, Christians believe individuals have no defence against Satan.

With Lilias Adie having therefore “died in the service of the Devil”, the Minister and the Kirk-Session of Torryburn were faced with a problem.

They believed resolutely, that just as God could resurrect the whole body of a good Christian in heaven, the Devil could reanimate, on Earth, the bodies of those who died in his service.

“Essentially, he controlled hard-to-spot zombie-like agents of evil, hell-bent on doing his bidding of corrupting, terrorising and harming the living.

“Clearly, Reverend Allan Logan, the minister of Torryburn was faced with a problem,” says Mr Speirs.

“He had an extremely hazardous ‘toxic waste’ problem on his hands.

“What could he do to protect himself and his parishioners?

“How could he stop Lilias from rising from the grave and coming back to wreak her revenge on her tormentors?

“The answer was simple: implement a suite of measures to make absolutely sure there was no way she could never rise from her grave.

With this in mind, the body of poor Lilias was locked in a large wooden trunk which was then buried deep in the estuarine mud, some 100m or so out into the inter-tidal bay off Torryburn, a spot covered for most of the day by the tide.

“For good measure, a large sandstone slab was also placed over her grave and of course all of this was done beyond the Gollet Burn which separated her cold, watery grave from the homes of her accusers and tormentors in the nearby village of Torryburn – as Burns says of witches in Tam ‘O Shanter, ‘a running stream they dare na cross’.

“This then was the depth of genuine belief in malign revenance in early 18th century Fife.”

Common beliefs of the time

Mr Speirs says it seems incredible to us today that educated Fifers in the 18th century could have believed so resolutely in revenance.

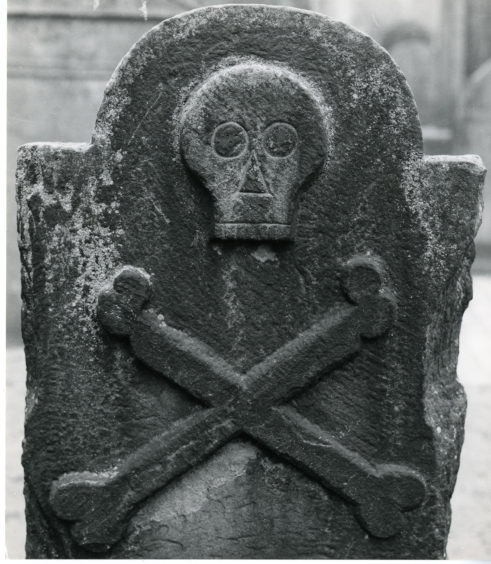

Yet historical evidence for this belief is actually quite common.

It can even be found in Scotland’s law codes of the 18th century, a time when the statue book prescribed fates even worse than death – execution followed by various forms of mutilation, enacted, in part, to ensure the condemned could never enjoy a whole-body existence in the afterlife.

It might seem strange then that at the same period, a form of post-mortem mutilation, or at least the deliberate putrification of bodies, was being engineered as an insurance policy against body-snatching and dissection.

“Body-snatchers, or resurrectionists as they tended to be known in late 18th/early 19th century Scotland, snatched bodies to sell to the newly-founded anatomy schools of Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen,” explains Mr Speirs.

“There were many devices employed to thwart the theft of buried corpses but in Crail churchyard, in east Fife, is an unusual building with a gory history.

“The plaque above the door makes clear exactly what this building was used for.

“It says: ‘Erected for securing the Dead: ANN DOM MDCCCXXVI’.

“A contemporary account explains how it operated.

Corpses

“’The house is most substantially built, and the roof arched; it is ventilated by slits in the walls, 12 inches by 3, (having an iron bar up their middle), so that no effluvia [odour] remains within the house; the door is made fast by three locks, the keys of which are confided to the care of three trust-worthy persons elected annually by the subscribers.

“‘The corpses deposited during the summer months are covered with sea sand, and they remain in that state from eight to 10 weeks, and 12 or 15 weeks during the winter, when they become utterly useless for the anatomist’.”

Mr Speirs adds: “Clearly, the key to whole-body resurrection in the afterlife wasn’t preservation or mummification, you just had to leave this life whole, something denied to all who graced the anatomist’s dissection table.”

Conversation