They fought for Queen and Empire and their bravery earned them the highest honour that can be bestowed on a British serviceman – the Victoria Cross.

But the medals won by Thomas Beach and Peter Grant could not ensure them honour in death and they were buried in unmarked graves in Dundee’s Eastern Cemetery.

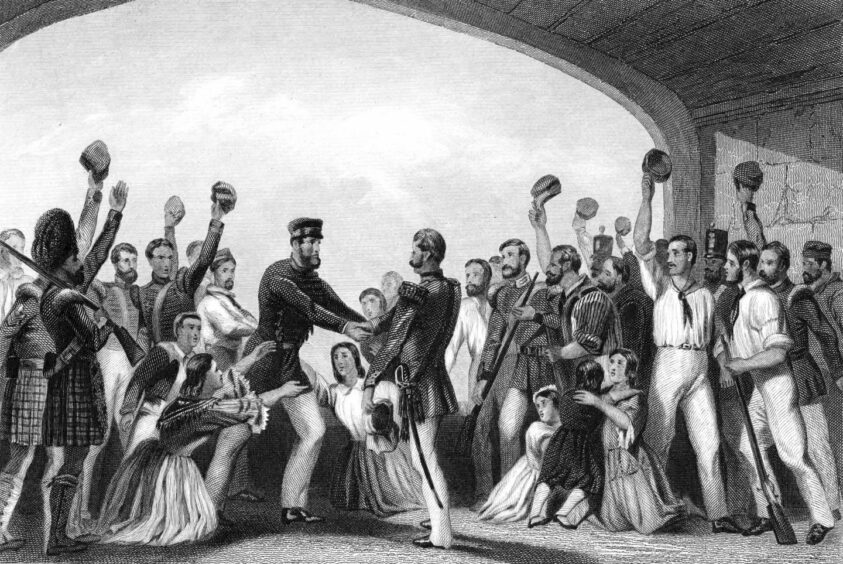

The Victoria Cross was the first decoration for gallantry to be open to all ranks and Queen Victoria was closely involved in its creation. She presented the first batch of medals to Crimean War veterans at a ceremony in Hyde Park.

Private Thomas Beach (or Beech), who some sources say was from Dundee and others Forfar, served with the 55th Regiment during the Crimean War.

He won his VC for his actions on November 5 1854, at Inkerman.

His citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry when on picquet duty in attacking several Russians who were plundering Lieutenant-Colonel Carpenter of the 41st Regiment, who was lying wounded on the ground.

“Beach killed two of the Russians and protected Lt Col Carpenter until the arrival of some men of the 41st Regiment.”

It is understood that Private Beach had a fairly chequered military career, being court-martialled twice but also receiving two good conduct medals.

He left the army in 1863 and returned to Dundee, staying in Exchange Street, but died the following year as a result of alcoholism.

His VC is one of five held in the medal collection at the Sheesh Mahal museum in India.

Private Peter Grant was born in Ireland and served with the 93rd Regiment in India.

He won his VC at Lucknow during the Indian Mutiny of 1857. He also came to the aid of a senior officer, killing five enemy soldiers who were attacking a colonel. It was one of six VCs awarded to his regiment during that campaign.

His citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry and displaying great courage, he killed five of the enemy who were attacking a colonel who had captured the rebels’ colours.”

Private Grant drowned in the River Tay in 1868 while on leave in Dundee and, like Private Beach two years before him, was buried in an unmarked grave. His VC is not part of a public collection and may be in private hands somewhere.

Although both men had won their country’s highest military honour, there was apparently no-one with the funds or desire to have them properly buried.

Instead they were interred in the poor ground, with no headstone or other marker, and it was not uncommon for one lair to be used for two or three burials.

It was intimated that there was no official records of exactly where they were buried at Eastern Cemetery, as was the case with all paupers’ graves.

Ensuring the men were properly honoured

Private Grant and Private Beach were largely forgotten until 20 years ago.

Former Dundee man Clay Hackett, who lived in Canada, came across references to the pair and wondered why they had not been accorded the respect their courage merited.

That led to the City of Dundee branch of the Royal British Legion Scotland starting a fundraising campaign to ensure the men were properly honoured.

Branch treasurer Frank Smith said they were not allowed to place any memorials on the actual ground itself, which was in effect a mass grave, but could put something nearby.

“The fact is that in the day that they actually died, in those days, soldiers were even less respected than they are today and so they were just cannon fodder basically,” he said.

“But these two men were both saving someone’s life, in both situations they were going to the aid of somebody who was in trouble, so it was nothing selfish, it was comradeship.”

The branch decided to purchase two benches, costing £700 each, have them suitably inscribed and installed on the edge of the poor ground, looking over the Tay.

Legion members laid a wreath in the area where the soldiers were buried as part of their Remembrance Sunday duties in November 2002.

Six months later a memorial parade was held at the Eastern Cemetery.

Over 100 people, including 23 standards from the Angus and Perthshire area council of the Royal British Legion Scotland, other ex-service associations and cadet groups, turned out to pay their respects.

In 2004 a descendent of Private Grant attended a commemorative service organised by the City of Dundee branch of the Royal British Legion Scotland at Eastern Cemetery.

Carole Spencer travelled from California and laid a poppy wreath on the memorial bench and experienced the bonds of the “regimental family”.

Old soldiers not even born when her relative drowned in 1868 moved her to tears with their heartfelt commemorative service.

Pastor David Taylor, chaplain to the City of Dundee branch of the Royal British Legion Scotland, conducted the service after lone piper James Fitzpatrick played a lament.

In his short address Mr Taylor spoke of a day the previous April when he attended the funeral of a Black Watch serviceman killed in Iraq.

The minister on that occasion pointed out the young soldier would not be forgotten by his two families: He had a natural family and a “regimental family”.

“Looking around that church in Perth I could see Black Watch men, some getting on a bit, others barely 18 and serving soldiers today,” said Mr Taylor.

“I knew then the strength of regimental ties.

“It was good, and is good, to belong to a regimental family.”

Relative of Victoria Cross hero touched by regimental bonds

He said he had no doubt Private Grant had pride in his regiment, the 93rd, raised in 1800 by the Duke of Sutherland.

He hoped Carole would take pride and comfort from the ceremony.

“I am sorry Carole had to come on such a sad occasion but it may be a happy memory as well of people who have gathered here to pay their respects to someone they didn’t know, someone who served his country as we all have done.”

Afterwards an emotional Carole said: “This is my first visit to Scotland but it won’t be my last. There is nothing we have to compare to this in the US, trust me.

“It is just so heartfelt and appreciated.

“Everybody has been wonderful.”

Conversation