Operation Kaleidoscope swung into action on November 14 1977 when 310 of Tayside’s 366 full-time firefighters abandoned their posts.

Over 1.25 million working days were lost during the first national strike in the fire service since Edinburgh pioneered the notion of municipal fire brigades in 1824.

It was such a novelty that the Fire Brigades Union had no strike fund and no provision in its rule book for such a contingency.

Even in 1926 the firemen received dispensation from the TUC to maintain their essential service during the General Strike.

But back in 1977 they meant business and voted by two-to-one to start strike indefinite action to secure a 30% pay rise along with a cut in hours from 48 to 40 a week.

The Labour Government had imposed a 10% pay limit, which the TUC supported, at a time when the country had been crippled by industrial unrest.

So, on the night of November 14, Home Secretary Merlyn Rees warned the country to be vigilant, and “to look out for the young and the old”.

Around 120 RAF personnel were assigned to temporary firefighting duties in Dundee, Perth and Arbroath, while the Navy looked after much of Fife.

So what was Operation Kaleidoscope?

Men and women were urged to equip themselves with buckets of sand and water, and ladders from their garden sheds, for use as makeshift firefighting equipment.

Householders were advised to keep a woollen blanket or a wet tea cloth on hand in case of chip-pan fire.

People were asked to be extra vigilant with electrical appliances and told that ashtrays should be emptied into an outside dustbin.

In Dundee, a group of Forest Park Road residents formed their own do-it-yourself firefighting team, having circulated neighbours with a list of “able-bodied men” who could be called out on a rota basis.

Over 100,000 fire protection booklets were distributed, advising people in Tayside to check, among other things, that they had a route to safety in the event of fire.

Owners of commercial premises were urged to arrange a watch system and extra vigilance was kept over public buildings such as Ninewells Hospital.

Radio and television networks would give constant advice during the strike while information was released on a daily basis through The Courier and Evening Telegraph.

Across Britain a total of 18,000 servicemen were rushed in from as far away as Cyprus to provide fire cover and, at any one time, around 10,000 troops were on duty over the nine-week strike.

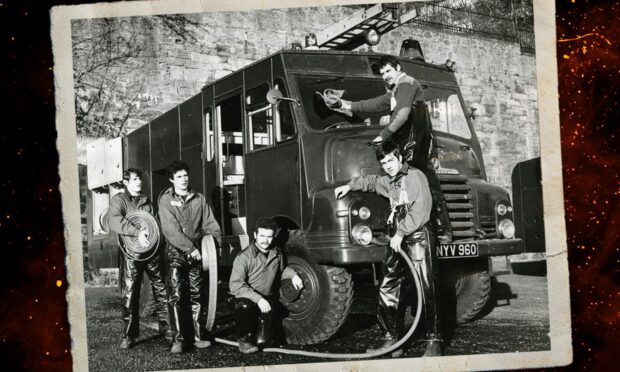

To aid the troops in their task, 900 Green Goddess fire engines, built in 1953 and originally ordered by the Home Office for use in civil emergency during the Cold War, were wheeled out of storage for use.

On November 18 in Dundee nearly 500 striking firemen took part in a demonstration and rally in support of their claim.

Elsewhere, there were sinister threats of violence against striking firemen who refused to answer emergencies. Two of three letter bombs sent to them exploded, without causing injury. Meantime, the Fire Brigades Union had to dissuade pickets from obstructing troops carrying out firefighting duties.

The picket ended after nine weeks when firefighters agreed to settle for a 10% pay rise with guarantees of increases in the future.

Several questions were duly raised about the emergency procedures employed during the 1977 strike. For instance, the MoD admitted that the use of troops was contrary to Queen’s Regulations, and the regulations had to be amended.

Of more concern were the allegations that the Bedford Green Goddess fire engines were hopelessly inadequate for modern working practices.

There were claims that many were unroadworthy, and that they had no radio equipment and had to rely on a police escort.

In any case, their top speed of only 35mph meant poor response times.

Nonetheless, the same ageing Green Goddess military vehicles were the only form of defence when firefighters staged a 48-hour walkout 25 years later in 2002.

The Fire Brigades Union (FBU) announced the strike dates following the result of a ballot of its 50,000 members in support of a near-40% pay rise.

The increase would have brought the average firefighter’s wage to around £30,000.

Tayside would have nine Green Goddesses covering Dundee, Perth and Arbroath, where normally 12 appliances would be on standby.

These were crewed by RAF personnel.

In Fife there were eight appliances operated by Royal Navy personnel.

The military’s fleet of engines were spread across the police regions and operations were being co-ordinated from 51 Brigade Headquarters in Stirling.

Tayside’s deputy firemaster Jack Hutcheon said: “The primary role of the military in this instance is to minimise as far as possible the danger to human life.

“I would urge all members of the communities we serve to be extra vigilant to the causes and effects of fire and plan their actions on the discovery of fire during any period of industrial action.”

Police escorts acted as “pilots” for the 35mph fire tenders around Tayside in a bid to ensure the fastest possible response to incidents occurring during the strike.

NHS staff were banned from using toasters or grills during the strike for fear of triggering a smoke alarm and putting unnecessary pressure on the Green Goddesses.

Wards offered a range of breakfast alternatives across the region during the strikes.

The military personnel had a quiet 48-hour period following the November 13 walk-out although bogus call-outs hampered the reduced fire cover.

The RAF commander in charge of emergency fire cover said his men had shown “an impressive level of dedication and commitment” in maintaining a service.

Wing Commander Richard Gammage said: “We have had 53 deployments in the 48 hours of the strike, starting at 18.01 hours on Wednesday, which we believe was the first call-out in the country, right up until the time we handed control back to the regular fire brigade at around 18.45 hours tonight.

“I am pleased that we have been able to deal with the incidents that faced us. Our response times have been very good and the average time has been comparable to that of the full-time fire service.

“We never said we could replicate what the fire brigade can do but I think what we have provided has been a very effective firefighting and light rescue service.”

Pay deal eventually agreed in 2003

Although the temporary cover was put to the test in the last couple of hours before regular firefighters returned to normal duty on November 15.

“We had to respond to eight incidents in the last couple of hours, ranging across the area from Arbroath to Forfar to Dundee and right out to Comrie,” he said.

“With the help of the retained firefighters who have been working with us, we were able to meet our requirements at those incidents.”

Mercifully, although there had been individual deaths across Scotland, none could be attributed to the 48-hour strike.

This began a series of walk-outs lasting between one and eight days.

In June 2003 at an FBU conference in Glasgow, the dispute ended with the firefighters accepting a pay deal worth 16% over three years.

Conversation