It’s a page-turner packed with family secrets and Arctic adventure that was inspired by Dundee’s whaling heritage.

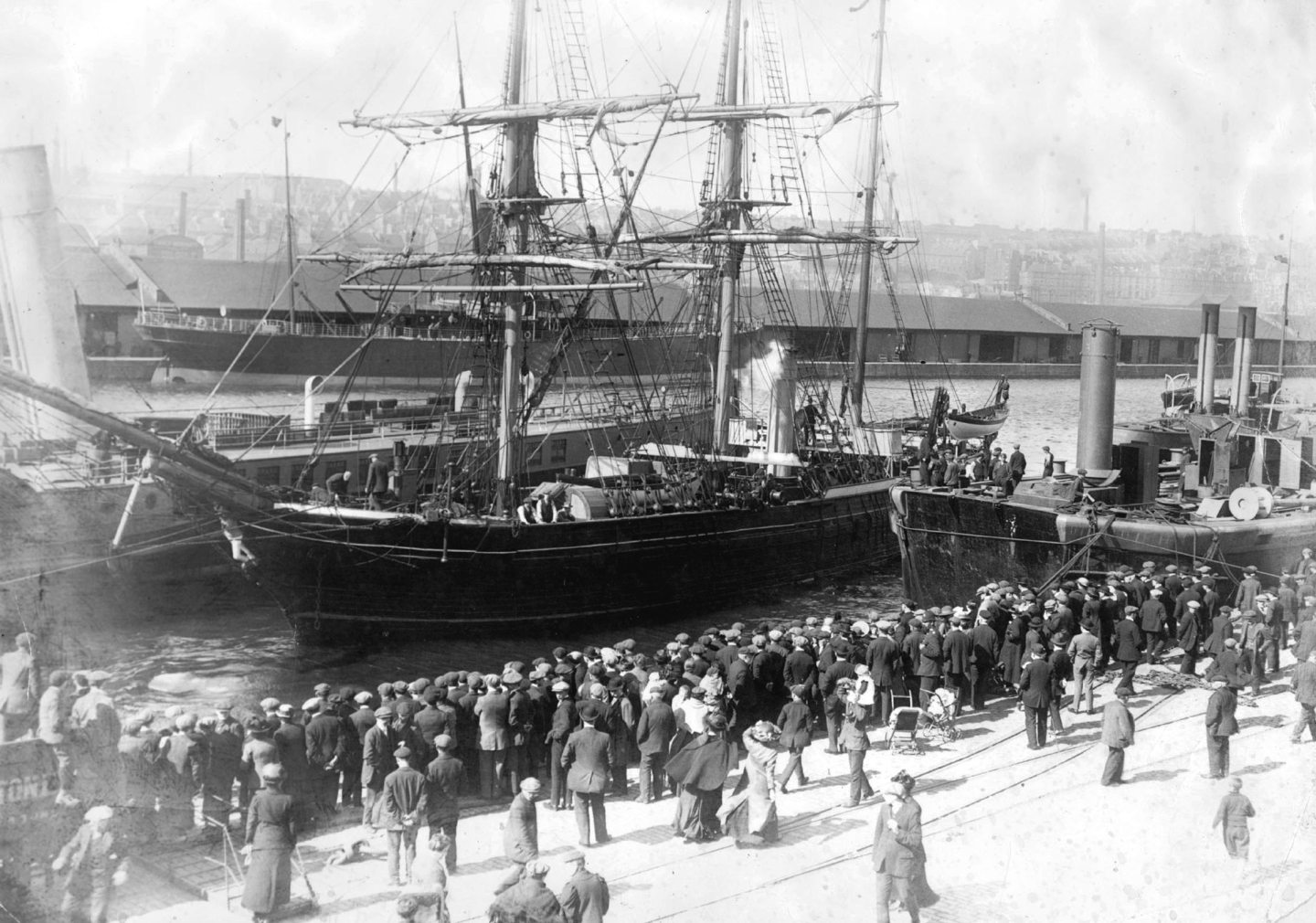

Dundee ships stalked the waves with harpoons from 1753 until the outbreak of the First World War, looking to kill whales in a trade that was vital for jobs and industry.

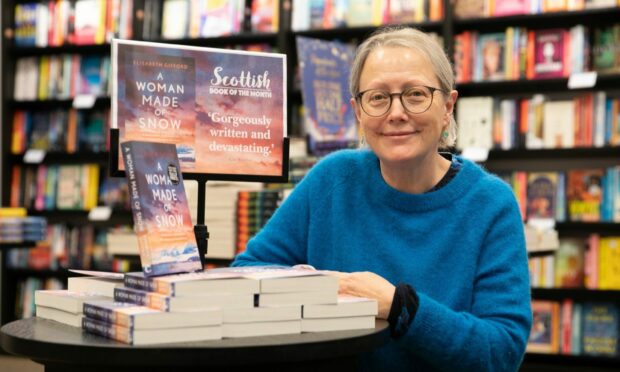

A Woman Made of Snow by Elisabeth Gifford has been released in paperback and the author has been sharing the local inspirations behind the best-selling novel.

The Kingston upon Thames-based author said: “A Woman Made of Snow was inspired by my visits to Dundee to see my grandsons, whose parents worked at the hospital in Dundee.

“I became fascinated by the hints at its whaling heritage.

“Listening to the voices of the mill girls at Verdant Works, a former jute mill where whale oil was used to process the flax, I had my first character.

“She’s a mill girl who falls in love with the mill owner’s son, even though he leaves Dundee as a surgeon on a whaling ship.

“His journey among the Inuit tribes of the Arctic turns his family history on its head and leaves a generational mystery.

“In the family home, based on Kellie Castle in Fife, with a new baby to care for, newly-wed Caroline tries to come to terms with the limitations of post-war life for a woman – and with her overbearing mother-in-law.

“Realising that a wife from the last century has been erased from the family history, she sets out to find who she really was, with devastating consequences.”

Echoes of the city’s whaling past

She has also been investigating the links between Dundee and the Arctic Inuit and said there are many reminders of the city’s whaling past round every corner.

Elisabeth said: “The Arctic Bar in Dundee is an unprepossessing pub with a modern frontage, but inside the dusty harpoon guns and photographs of ice-bound ships displayed around the walls indicate that this was once the pub where Victorian whaler men would go to collect their pay at the end of a six-month voyage.

“The new V&A museum is built in the shape of a ship, seeming to set out over the Tay, because it stands on the site of what was once the Earl Grey dock where whaling boats berthed over the last two centuries.

“Next to it is the ship RRS Discovery. Of course, Scott commissioned this converted whaling ship, with its triple-reinforced hulls, for his Arctic expedition.

“The McManus holds many Inuit artefacts, brought back by Victorian whaler men, along with a stunning collection of photographs of Inuit and whaling boats crews, and several diaries written by various ships’ surgeons, who were usually medical students wanting adventure and funds for the summer.”

A young Mary Shelley spent her formative years living with 19th Century jute barons, the Baxter family.

Shelley, who is believed to have lived in a house near what is now Dundee’s South Baffin Street, took her inspiration from the whalers and the ships coming back into port.

“Shelley would have listened to tales from Dundee whaling captains,” said Elisabeth.

“At the end of her novel, Frankenstein’s monster flees into darkness across Arctic waste.

“Ridley Scott’s The Terror and the BBC drama The North Water continue in this gothic tradition of man set against extreme taboos.

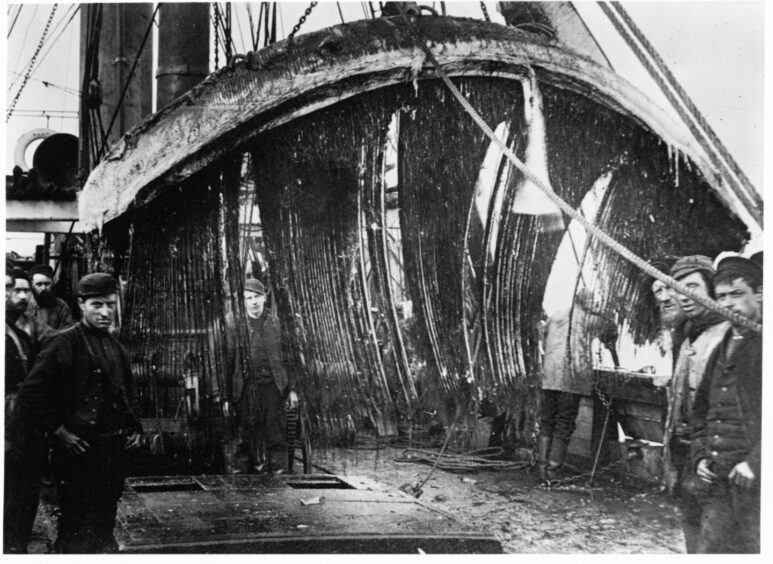

“For the novel A Woman Made of Snow, I wanted to evoke the daily lives of the whaler men and the Inuit that they met, worked and lived with.

“The Dundee whaling industry lasted longer than in any other whaling port in Scotland and England.

“With steady work available and a strong church tradition, the whaler men of Dundee were by and large sober artisans – though with plenty of the famous ‘wild rough lot’ found in most whaling ports.”

Dundee whaling crews and the Inuit

Whaler men did earn well. Many of them never seeing a summer at home, they brought their pay home to wives in Dundee who were able to run respectable homes.

Dundee whaling crews also interacted with the Inuit.

They adopted the polar technology of the Inuit tribes they met and worked with, commissioning seal skin boots and suits for the men for winter.

From the early 19th Century, as whales declined in numbers, Scots ships from Aberdeen and Dundee began to overwinter on Baffin Island and the far side of Hudson Bay.

Elisabeth said: “They wanted to be ready to begin hunting as soon as the ice broke up.

“Each ship would hire several Inuit or even a whole tribe to supply fur clothes and boots and to help with hunting for seal and whales.

“In exchange, the Inuit received knives, beads, sewing machines and sometimes their own small boat to hunt the whales for the Scotsmen.

“The Inuit hunter gatherers were surprised to be given three meals a day, even when they were not hungry, and discovered a taste for coffee, cocoa and treacle.

“The Inuit learned to play the accordion and danced Scots reels on deck with the sailors.

“Since the Inuit were free to pick the boat they worked for, with different tribes working for US or Scottish boats, the interchange was mostly good humoured and considerate.”

In spring the Inuit would leave the winter hunting and their ice houses to make a summer camp of skin tents on the shore, setting a lookout for the first sign of a whaler.

The first puff of smoke from the steam engine was the cause of celebration.

A family affair for Captain Murray

Some of these collaborations between Inuit and the whaler men lasted more than two generations.

Captain Murray of Dundee, who had a Dundee wife and an Inuit wife, took his Inuit son back to Dundee to be educated alongside his Scots son.

Both boys later became whaler captains.

Contact with western ships brought benefits to Inuit communities which sometimes starved in winter, but also problems.

Only a handful of ships cleared from north-east ports between 1900 and 1914.

The First World War effectively brought Scotland’s bloody whaling odyssey to a close.

Elisabeth said: “Inuit who came to rely on the boats suffered catastrophic results when the boats stopped coming, and when diseases such as smallpox were imported.

“Up until the 1980s many elderly Inuit retained happy memories of their childhood among the whaler men, dances on board and good food on exciting, great ships.

“Dorothy Harley Eber collected some of these oral stories in When The Whalers Were up North. These were a valuable resource while writing A Woman made of Snow.

“As were the diaries of crewmen on the boats.

“The most evocative sources, however, were the photographs of the Inuit from Cromer or from the Dundee McManus collections, often showing the people mentioned by Eber in her collection of oral stories.

“I hope A Woman Made of Snow will serve to bring to life some of these early encounters between Victorian Europeans and the last hunter-gatherers of Arctic Canada.”

- A Woman Made of Snow is out now in paperback.

Conversation