With today’s royals spending most of their time at Balmoral or Holyrood House, it’s easy to forget that at one time it was Forteviot in Perth that held the heart of the royal family.

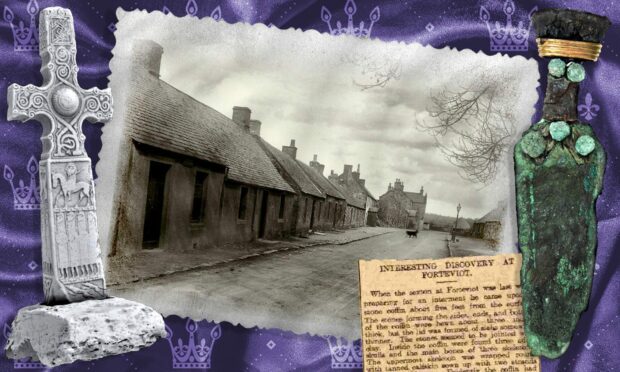

One of the earliest identified royal centres in Scotland, the ninth century palace was situated in a village which has one of the largest concentrations of prehistoric ritual monuments identified in Britain.

Tom Welsh, author of Fake Heritage – Solving Mysteries, believes that the discovery of a skeleton at Forteviot, wrapped in a leather shroud, may prove to be the final resting place of one of Scotland’s earliest royals.

Other royal graves such as Prince Edward, son of King Malcolm III, were discovered at Dunfermline Abbey in 1849 wrapped in similar shrouds.

Tom takes up the story.

The history of Forteviot

He said: “Forteviot is supposed to have been the location of a royal palace, where, according to the Pictish Chronicle, Kenneth MacAlpin died in AD 858.

“It is traditionally associated with later kings such as Malcolm Canmore (1057-1093).

“A modern plaque proclaims the connection with Kenneth MacAlpin, and a palace here from the 7th to 12th century.”

Cináed (Kenneth I) mac Ailpín, ‘the first king of the Scots who ruled in Pictland’, died at the royal centre of Forteviot, Perthshire, #OTD in 858. He was succeeded by his brother Domnall. Reconstructed Forteviot Arch. pic.twitter.com/mGGg2PR5YU

— North Ages (@NorthAges) February 13, 2022

The ninth century was a period of major social and political change in Scotland.

The eastern kingships of Pictland and the western kingships of the Scots came together and formed the new kingdom of Alba by AD 900.

With Forteviot in use at that time, it is favoured by archaeologists as a strong site to study Early Medieval Europe.

The leather shroud found in Forteviot

He said: “One of the great mysteries at Forteviot is the leather shroud found there in 1906.

“Royal burials sometimes include leather shrouds, for example in the case of Robert the Bruce.

“The most famous example is the grave attributed to Prince Edward, son of King Malcolm III (Malcolm Canmore).

“This was discovered in Dunfermline Abbey during renovations in 1849.

“Given the existence of a royal palace here, the Forteviot leather shroud might indicate a royal personage.”

Tom explained how the grave was discovered over a century ago.

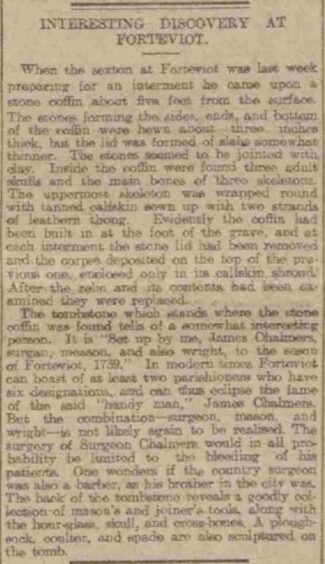

He said: “In August 1906, workmen were digging a new grave in Forteviot churchyard, next to an ornamented stone for James Chalmers, dated 1739.

“About five feet down, they found a stone coffin made from sandstone slabs.

“The slabs were three inches thick, forming four sides and the bottom, sealed together with clay.

“Several thinner slabs covered the top.

“Within the coffin were three adult skulls and residues of skeletons, one on top of the other.

“The most recent was wrapped in a leather shroud.

“It was made from tanned calfskin and sewn up with two strands of leathern thong.

“This, and the bones, were carefully replaced in the coffin, and it was covered over.”

The Dunfermline shroud

Tom said: “It is interesting to compare the Forteviot shroud with the Dunfermline shroud.

“The one at Dunfermline was found in one of two massive stone coffins, near the site of the altar of the original church of Dunfermline Abbey, under a 1508 grave slab.

“The remains had been entirely enclosed in leather and closely stitched with strong leather thongs down the back from the neck to the heels, and even along the soles of the feet.

“There were few remnants of bones contained.

“The Dunfermline shroud was found in the location where Malcolm Canmore had originally been laid to rest.

“But in 1250, Alexander III had Malcolm’s remains reburied in the Choir of the Abbey Church.

“The theory is that the shroud contained the body of Prince Edward, Malcolm’s eldest son.

“Malcolm had invaded England and besieged Alnwick, but he was repelled in a battle there on 13th November 1093.

“Both Malcolm and his son Edward were killed, and initially buried at Tynemouth Priory.

A Royal grave?

So could the leather shroud at Forteviot mark the remains of a significant Royal personage?

Part of the answer lies in identifying the whereabouts of the royal palace, and Tom said the discovery of the skeleton in 1906 could help find it.

Tom said: “A large building on a mound (known as Haly Hill) was reputedly washed away by the river in the latter half of the 18th century.

“Descriptions in 1772, and in the 1780s and 1790s, chart its gradual disappearance.

“The first Ordnance Survey maps in 1866 place Haly Hill north-west of Forteviot church, on the east (right) bank of the Water of May.

“The river was undermining ground near the church in 1768.”

The undermining was caused by the river undercutting the steep ground, washing away material at the base so that ground above it toppled over.

Tom added: “After several attempts to add barriers, cut new channels and raising training banks, this was prevented.

“However, the consequence was more erosion downstream.

“The river frequently broke its banks and found new channels.

“A plan produced in 1794 for a boundary dispute shows where the river crossed the boundary.

“It indicates the location of curves in the river, and that helps understand where there was erosion at the time.

“It suggests there was no erosion at that time north of Forteviot where Haly Hill is supposed to have stood.

“The erosion occurred mainly towards the west (left) bank.

“Instead, others favour an elevated site north-east of Henn Hill farm as a site for the palace.

“It is on the west bank, south-west of the church.

“This was being eroded in the latter half of the 18th century.

“There is a promontory here, cut into by an old river meander which has the potential for defence.

“Certainly the palace could be looked for on either side of the valley, a little upstream of Forteviot rather than downstream.

“There is much more to be discovered here.”

Final verdict

It will take further research to prove whether the leather shroud discovered at Forteviot really is the final resting place of one of Scotland’s oldest royals.

However, its discovery serves as a reminder that Forteviot was once a centre of great importance in Scottish history, and one where historians have a lot more to learn.

It is proof that Scottish history is not merely the preserve of archaeologists, but one in which we can all share.

The story carries on.

Conversation