Michael Alexander speaks to Lord Alf Dubs – a child refugee who fled the Nazis before World War Two, becoming an MP, CEO of a refugee charity and member of the House of Lords – and who has now been honoured by St Andrews University.

He is the Labour peer who fled the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia through the Kindertransport scheme, which rescued so many Jewish youngsters before the Second World War.

Lord Alf Dubs, who received an honorary Doctor of Law (LLD) from St Andrews University on Tuesday November 29, has spent his career standing up for the rights of refugees – especially children.

The now 89-year-old, whose aunts and uncles perished in the Holocaust, successfully campaigned for UK Government legislation to grant special status for unaccompanied child refugees, known as the ‘Dubs Amendment‘.

Through his lived experiences, he is forever grateful to Britain for giving him a safe home.

In an interview with The Courier, however, Lord Dubs despairs at the “increasingly negative and hostile” attitudes of the UK, and some other western governments, towards refugees.

He has also warned that through the consequences of war, economics and climate change, the world is going to have to face up to – and “sensibly manage” – even greater migrations of displaced people.

Escape from the Nazis

Lord Dubs was only six-years-old when in March 1939, following the German annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938, the Nazis occupied the Czechoslovakian capital Prague.

His Jewish father, whose family came from Northern Bohemia, left immediately.

When the Nazis arrived, he remembers having to tear a picture of President Benes from his school book and stick in a picture of Hitler.

In March 1939, all the schools were supposed to go to Wenceslas Square when Hitler visited to proclaim the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from Prague Castle.

However, after his mother went to the school and said they were far too young, his class didn’t go.

Lord Dubs remembers there were German soldiers all over Prague.

His mother, of Austrian descent, tried to get permission to leave the country.

However, she was refused and was literally thrown down the stairs “in a heap”.

The only hope she retained came from the fact they threw her passport after her.

Lord Dubs’ lifeline to survival came in July 1939 when his mother got him on to a Kindertransport.

These were arranged by Nicky Winton who got 669 children out of Prague to the UK, alongside more than 9,300 other Jewish children from across Europe.

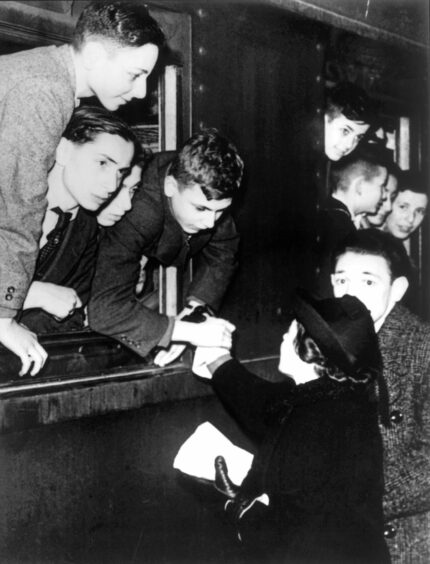

Emotional scenes

Lord Dubs still remembers the scenes at Prague railway station like it was yesterday.

“I can still see it in my mind’s eye – Prague Station, anxious tearful parents saying goodbye to their children and German soldiers with swastikas in the background,” said Lord Dubs.

“I was one of the youngest at the age of six.

“The next night we got to the Dutch border.

“I remember the older children cheered because we were out of reach of the Nazis.

“I didn’t know the significance. I sensed something important was happening but I didn’t really know what.

“I was looking out the window but couldn’t really see anything because it was dark.

“We crossed Holland. Got to the Hook of Holland, crossed to Harwich, then got the train to Liverpool Street.

“I arrived in a London ready for war with barrage balloons and all that sort of stuff.

“We had dog tags on. Everybody had to be assigned to a family member or to a foster family.

“I was very lucky – luckier than many – because my father was waiting for me at Liverpool Street station.

“Almost miraculously, my mother managed to get out of Prague a few weeks later. She arrived in London on August 31, 1939.

“Germany attacked Poland on September 1, so it was the last possible moment she could have come.”

Family tragedy

As a Czech and German speaker, Lord Dubs had to learn English fast.

Both he and his parents initially moved to Northern Ireland where a refugee colleague of his father’s had got permission by the British government to open up a disused factory, offering work.

However, just few months later, tragedy struck when Lord Dubs’ father had a heart attack and died.

He and his mum moved back to England, settling in the Manchester and Blackburn areas. Lord Dubs spent part of the war in a school run by the Czech government.

In 1947, after the war, Lord Dubs’ mother went back to Czechoslovakia to see what was left.

However, she quickly discovered that most of the people they knew had fled or perished in the concentration camps. Their flat had also gone.

Amongst those who perished were Lord Dubs’ father’s cousins.

They had “taken their chances” by staying in Prague in 1939.

However, when the Gestapo came for them in 1942, one took their own life by biting on a cyanide pill and the other had been taken to Auschwitz where they didn’t survive the gas chambers.

With the Communists about to take over in Czechoslovakia, Lord Dubs’ mother decided they should stay in England – and he’s delighted they did!

Interest in politics and refugees

By the age of 12, Lord Dubs was passionately interested in politics.

Leaving school, he studied at the London School of Economics and eventually got a job in marketing.

He became a local councillor – initially thinking that with English being his third language and his background, he couldn’t possibly stand for parliament.

Fast forward to 1979 and after persuasion to stand by friends, he was elected Labour MP for Battersea South.

A few years later he was made Shadow Minister for Immigration, Refugees and Race Relations.

“I was interested in politics at 12 when most of my contemporaries weren’t,” he said.

“It possibly came from the fact that I thought if evil men can do such terrible things, maybe politics can also be used for making things for the better.”

He lost his seat in 1987, but became CEO of the Refugee Council and joined the House of Lords in 1994.

All along he’s been committed to campaigning for refugees and in 2016, the anti-Brexiteer moved an amendment that the UK should take unaccompanied child refugees from Europe, especially Calais and the Greek Islands.

The Tory government fought hard against this but eventually gave way because of the weight of public opinion – though they arbitrarily put a cap on numbers.

Another battle followed to continue the right to family reunion for unaccompanied child refugees.

It’s an argument, he says, that must continue.

Gratitude to Britain

“There’s a little thankyou plaque in the House of Commons on behalf of the 10,000 children who came on the Kindertransport in 1938/39 from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia,” he said.

“Britain was the only country that did anything then.

“I think on the whole people in the UK believe in the humanitarian.

“They are essentially believers in decency and looking after vulnerable people.

“But sometimes we have governments that spread a different message, and that’s rather depressing.

“In parts of the continent, extreme right wing parties have exploited the refugee issue, in order to get some electoral advantage.

“Here, it’s deeply deeply shocking when you get a Home Secretary who says we’re getting ‘invaded’ by refugees.

“Invasion is what happens when enemies attack a country.

“That was a very hostile comment to make along with a lot of other things the government have been making.

“It makes it harder for local communities to feel they can be supportive of refugees.

“They still are but it works against that instinct by sending out what is a rather poisonous message which I think is a very sad comment on the attitude of this and the previous Home Secretary.”

Parallels with Ukraine

Despite government obstacles, the British public’s “open and generous” welcoming of Ukrainian refugees in 2022 draws parallels to the welcoming of Jewish children before the war and settling of displaced persons after it.

Lord Dubs thinks the reason for the Ukrainian support lies partly because the horrors have been seen on TV – probably less so than Syria, North Africa or Afghanistan.

People also probably feel more sympathetic because they are “white Europeans”.

But as far as he is concerned, all refugees should have equal rights.

While he believes Britain should be taking more, and that there should be more British-French collaboration – as seen recently – and more European-wide collaboration to manage the situation, the focus shouldn’t be on numbers.

It should be on the human rights of individuals – especially children.

Need to work together

“I feel that Europe’s attitudes to refugees are becoming more hostile,” he said.

“I’m depressed by that. I’m depressed by the political rhetoric surrounding the issue. We can all do better.

“On a positive side, I’ve been to Calais – what’s left of ‘The Jungle’.

“I’ve been to the Greek islands. I think what we’ve got is wonderful volunteers in this country who go out there and work in refugee camps and help their fellow human beings.

“There are some positive, good things happening. Some of the NGOs are doing fantastic work.

“But I’m finding the attitudes of governments is becoming increasingly negative and hostile.

“People need to realise that in a world with wars, economic strife and climate change – the world is going to have to face more movement of people not less movement.

“What we’ve got to do is manage it all sensibly, and work together as one.”

Conversation