He used to sit silent and high, pondering the age that outstripped his miracles of steam from his rooftop perch on Dundee’s Upper Dens Mills.

James Watt looked his last over the roofs of Blackscroft 70 years ago after being pulled down from the top of what was once the biggest of Baxter Brothers’ factories.

The 6ft-high statue was dislodged for safety reasons and reassembled in a shadowy corner of Baxter’s long joiners’ shop at the linen factory in Dundee’s Princes Street.

A world of shavings and sawdust and saws and planes was a comedown but mystery still surrounds what happened after the statue was taken down in 1952.

Will it ever be solved?

Who was James Watt?

James Watt was born in Greenock in 1736 and went on to become one of the world’s most highly regarded inventors and engineers for his work on the steam engine.

Watt helped turn Britain from cottage and craft production into an industrial powerhouse and made it possible for Dundee to become jute capital of the world.

So what were the roots of the Baxter Brothers’ firm?

William Baxter leased a water-powered spinning mill at Glamis in 1818.

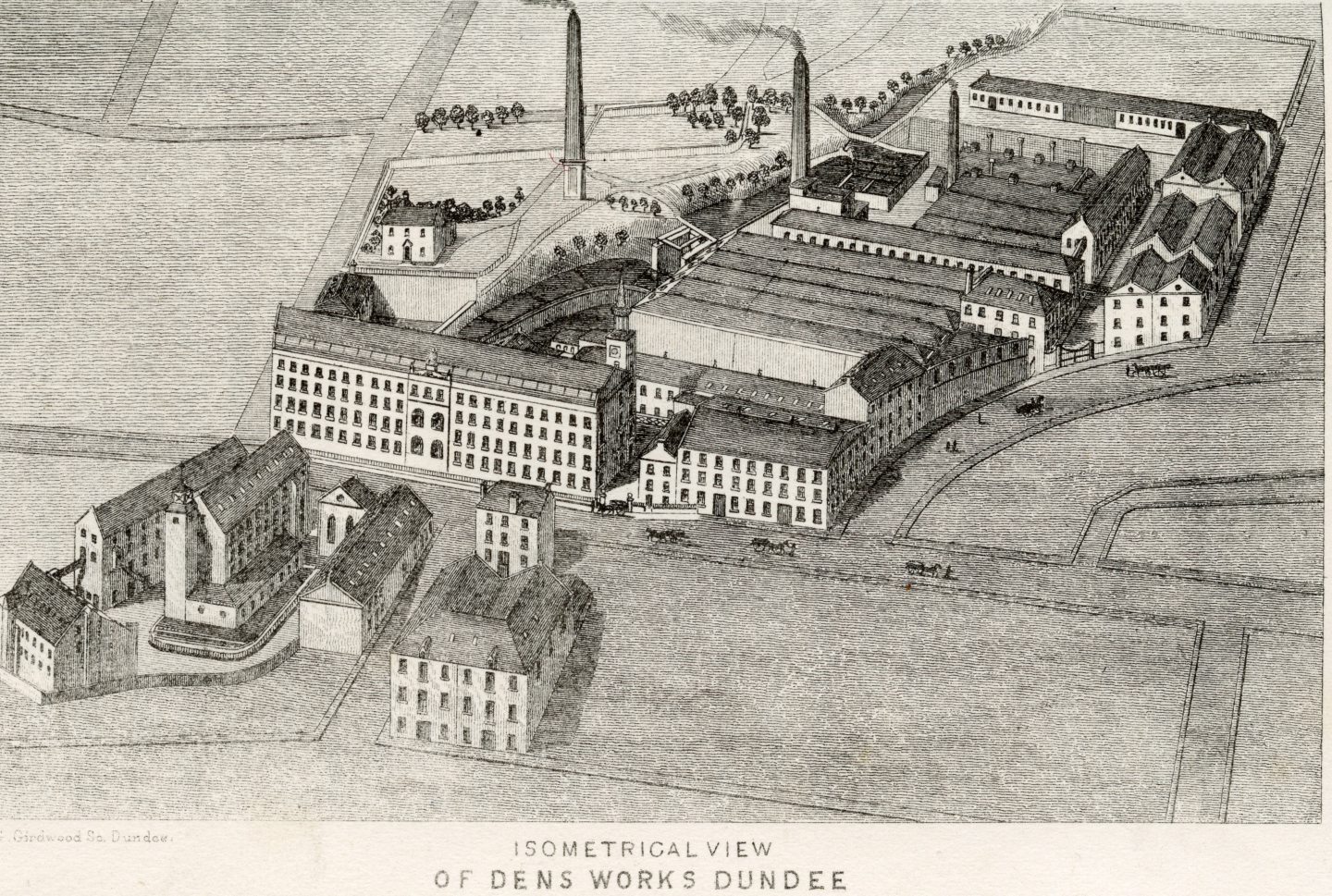

So successful was the Glamis venture that Baxter decided to extend his activities to Dundee and built his first mill on the Dens Burn with his eldest son Edward.

Baxter Brothers’ Lower Dens Works consisted of a 15-horsepower spinning wheel and in the course of time would become the world’s largest linen manufacturers.

A wooden statue of James Watt made by a ship’s figurehead carver called James Law became a well-known landmark when Upper Dens Mill was remodelled in 1852.

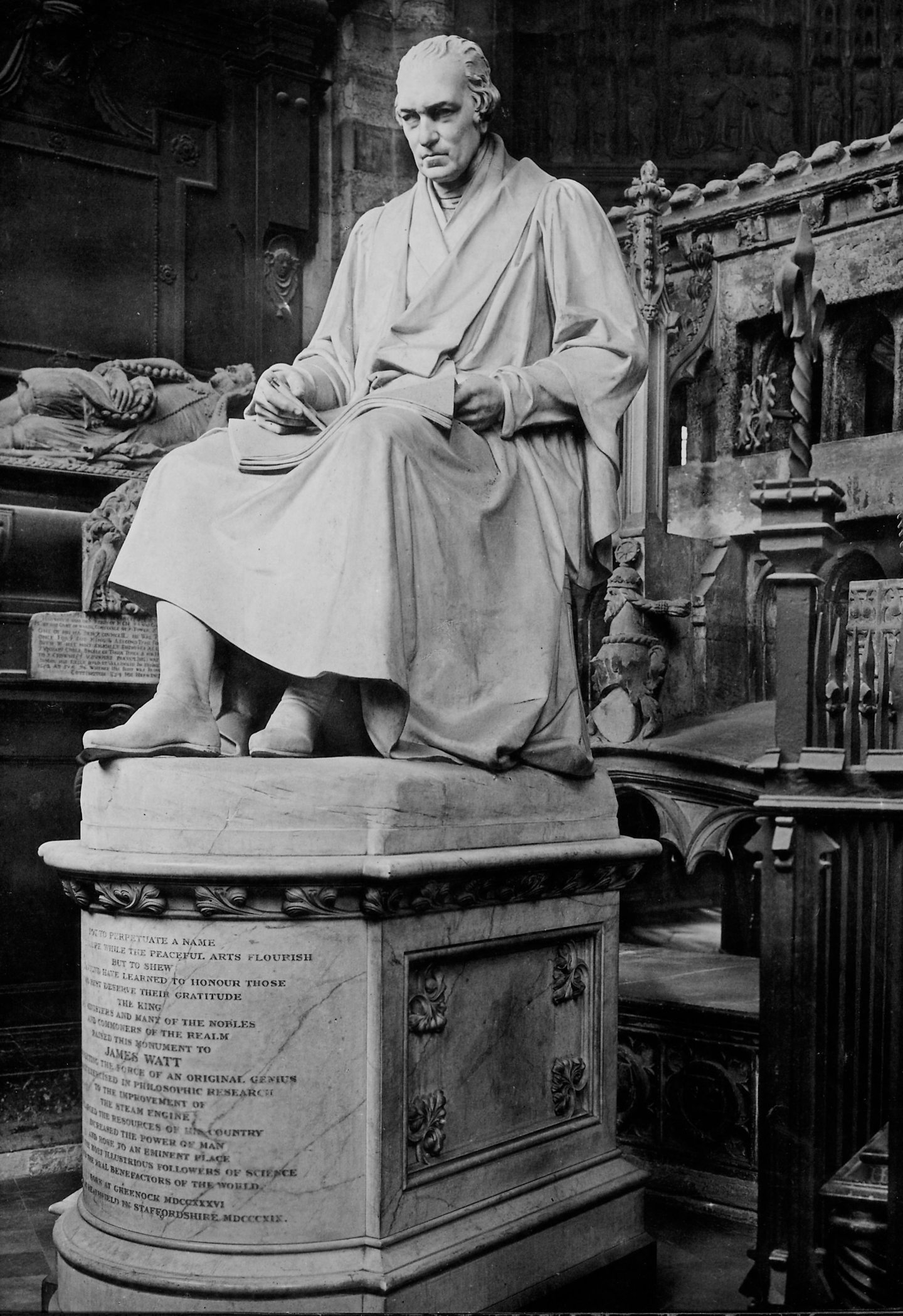

Watt was represented as sitting down with a pair of compasses in one hand, and a drawing, which was resting on his knees, was being steadied with his other hand.

The Courier recorded the statue unveiling back in 1852: “It was a happy thought to place a statue of James Watt on the highest part above the engine houses.

“If any man deserved to be lifted up to a place of honour, it was the man who made such a large building possible by giving the world the steam engine.”

It was a smaller version of the very large white marble statue by Sir Francis Chantrey which was erected in St Paul’s chapel in Westminster Abbey in memory of Watt in 1825.

Other mills which dotted the skyline when Dundee was known throughout the world as Juteopolis also had their own symbol including the wooden eagle above Eagle Jute Mills in Victoria Street and the exotic camel and rider modelled on Lawrence of Arabia which topped the gate of Gilroy Brothers’ Bowbridge Works in Thistle Street.

Dens Works stood out from the crowd

Another notable feature at Dens Works was its chimneys which were designed to resemble Egyptian obelisks and allowed them to stand out amongst the forest of belching factory chimneys which spewed out dirty smoke across the city.

Dr Kenneth Baxter from Dundee University’s archive services said: “Peter Carmichael, manager of Dens Works from the 1830s (and partner in the firm from 1852, becoming senior partner in 1872) was a talented engineer and had a great interest in science and engineering.

“I think there is little doubt he would have approved of Watt’s statue being at the top of the Works.”

“A Historical and Descriptive Guide to Dundee written by Charles C. Maxwell and published by George Girdwood in 1858 included an illustration of Dens Works.

“Maxwell noted that any guide to Dundee would be ‘incomplete without some notice of the immense Spinning Mills and Factories where… so large a proportion of our population are engaged’ and highlighted Dens Works as being particularly important.”

The firm, which gifted, amongst other things, Baxter Park to the city.

Dr Baxter said Baxter money notably founded the forerunners of both universities, and members of the firm, notably David Baxter, but also Peter Carmichael, gave key donations toward the Albert Institute.

Dundee Royal Infirmary also received much Baxter money.

Watt surveyed the passing show for decades and looked out from Princes Street to the Dundee and Arbroath Joint Railway and the harbour where steam meant so much.

He was removed in 1911 having withstood the elements for generations.

The end was nigh

Watt was re-carved as the wood was deteriorating.

The new figure of Watt was carved from yellow pine wood by carver Alexander Fair from Trades Lane and was an exact model of the old blackened statue.

On account of its bulk the statue was taken to the site in sections and finally finished in position at Upper Dens Works in September 1912.

On the wall of an office room there was even a spare face for him.

Watt was painted white to give him a fresher appearance before the 1914 royal visit of King George V and Queen Mary where the building was decked out in bunting.

In 1952 the statue of Watt had deteriorated again and was taken down when the windows of the Upper Dens mill were modernised in galvanised steel.

On both sides of the statue were metal aprons, which, together with the stonework underneath, were becoming dangerous.

Watt was dismembered for the flitting and was reassembled.

But he would never be the same again.

Watt was retired to Baxter’s long joiners’ shop with a large crack.

It was fitting perhaps that the foreman joiner at Baxter’s was Nathan Veitch from Barnes Avenue who helped set Watt on his pinnacle back in 1912.

Upper Dens Works eventually closed in 1978 after the textile industry in Dundee was hit by a series of booms and slumps.

The building was developed by Hillcrest Housing Association between 1983-1985 and the galvanised steel windows were replaced back into timber in 1986.

So what happened to the statue?

Monifieth man Kenneth Miln is among those hoping to discover Watt’s fate.

Kenneth served an engineering apprenticeship with James F Low and Co Ltd and went to India to install and commission machinery at mills in the Calcutta area.

He served over six years between India and Pakistan in the jute industry, over 16 years in Africa and three years as works manager of Ogilvy Bros jute mill in Kirriemuir.

He also helped to set up the jute machines in Verdant Works in Dundee.

Kenneth said: “People living and working in Dundee during the heyday of the city’s jute industry would have seen a number of iconic images adorning mill buildings.

“A prime example of which was the statue of Scottish inventor James Watt who built the first steam-engine capable of operating machinery in 1776.

“Watt’s engine, with a few modifications, was the technology leading to the great horizontal steam-engines which powered Dundee’s then-burgeoning jute industry.

“Watt’s iconic image served to remind both mill employees and members of the public of his contribution to Dundee’s industrial development.

“With the advent of steam-power came larger mills and an increasing demand for more workers which resulted in a huge influx of people into the city.

“Dundee’s great mills, once filled with clattering machinery operated by hard-working folk communicating by sign-language in a stoor-laden atmosphere, were an unforgettable part of the city’s vibrant industrial history.

“However, as with most industrial empires Dundee’s jute industry began a gradual decline which was hastened by the transfer of process-technology, mill-machinery and skilled personnel to India, beginning in the late 1800s through to a few years after the Partition of India in 1947.

“The establishment of jute mills in India sounded the death-knell for Dundee’s jute industry which caused many of the city’s great mills to fall silent and derelict.”

Watt’s statue was one of a number of icons carved by highly-skilled craftsmen.

The whereabouts of Watt’s statue remains, to date, a mystery, similar to that of the wooden bird which flew off from Eagle Jute Mills when it became a kitchen shop.

The camel was dismantled from the top of the gates at Bowbridge Works in 1955 and dumped unceremoniously in a hole dug out for a new weighbridge.

Was James Watt afforded a similar burial or might there be a happy ending?

Kenneth said: “Hopefully the missing statue may yet be found.

“The wooden carving of James Watt serves as an icon to remind us of his contribution to the industrial revolution which gave the world the steam engine.”

Conversation