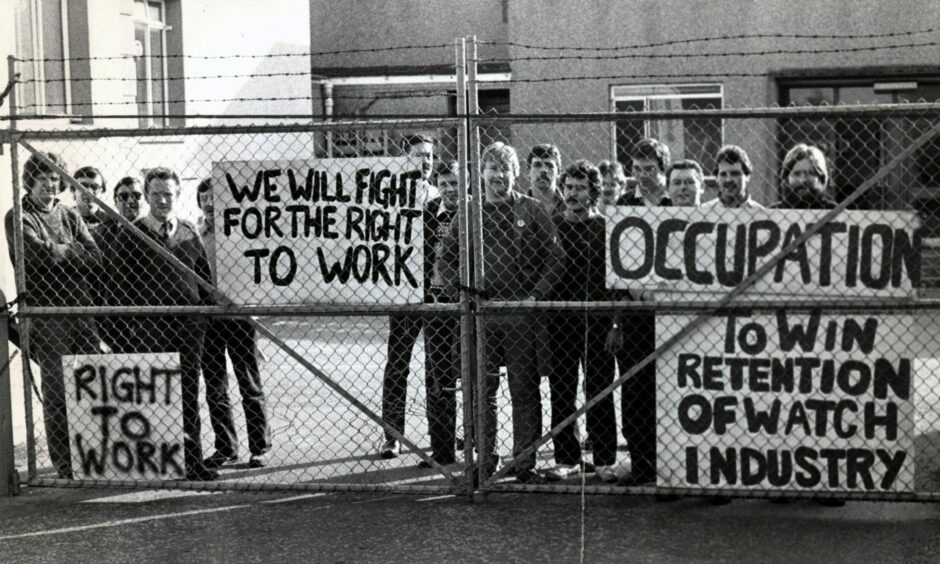

Timex workers barricaded themselves in the plant for six weeks to oppose 1,900 redundancies which were announced 40 years ago.

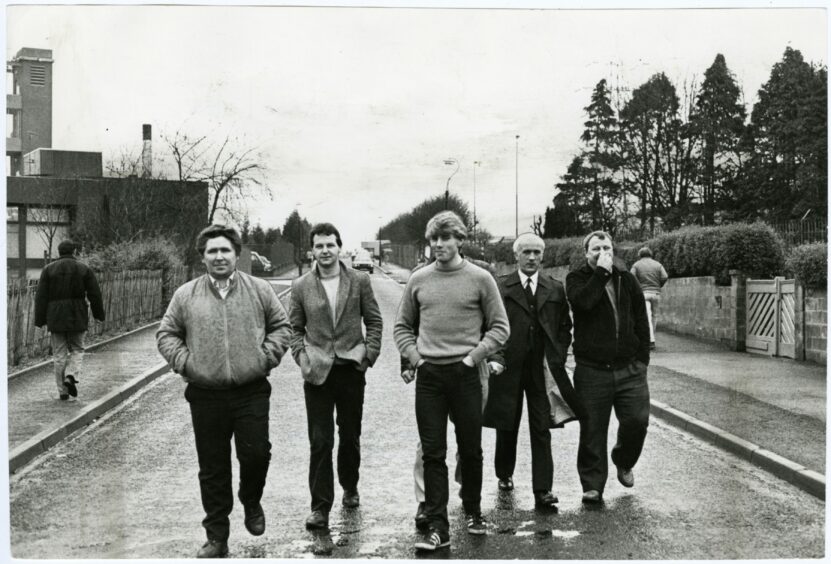

The company’s decision on January 10 1983 was Dundee’s darkest industrial hour and sparked months of unrest which ended with the seizure of the factory.

Back in its mid-1960s heyday, the Timex facilities in Dundee were massive — 240,000 square feet at Milton of Craigie, 190,000 square feet at Dunsinane Avenue and the flagship factory at Harrison Road was the UK’s largest supplier of watches.

By the end of the 1970s, the American business had started to feel the pinch of the world recession and the relentless pressure of cheap imports of digital watches.

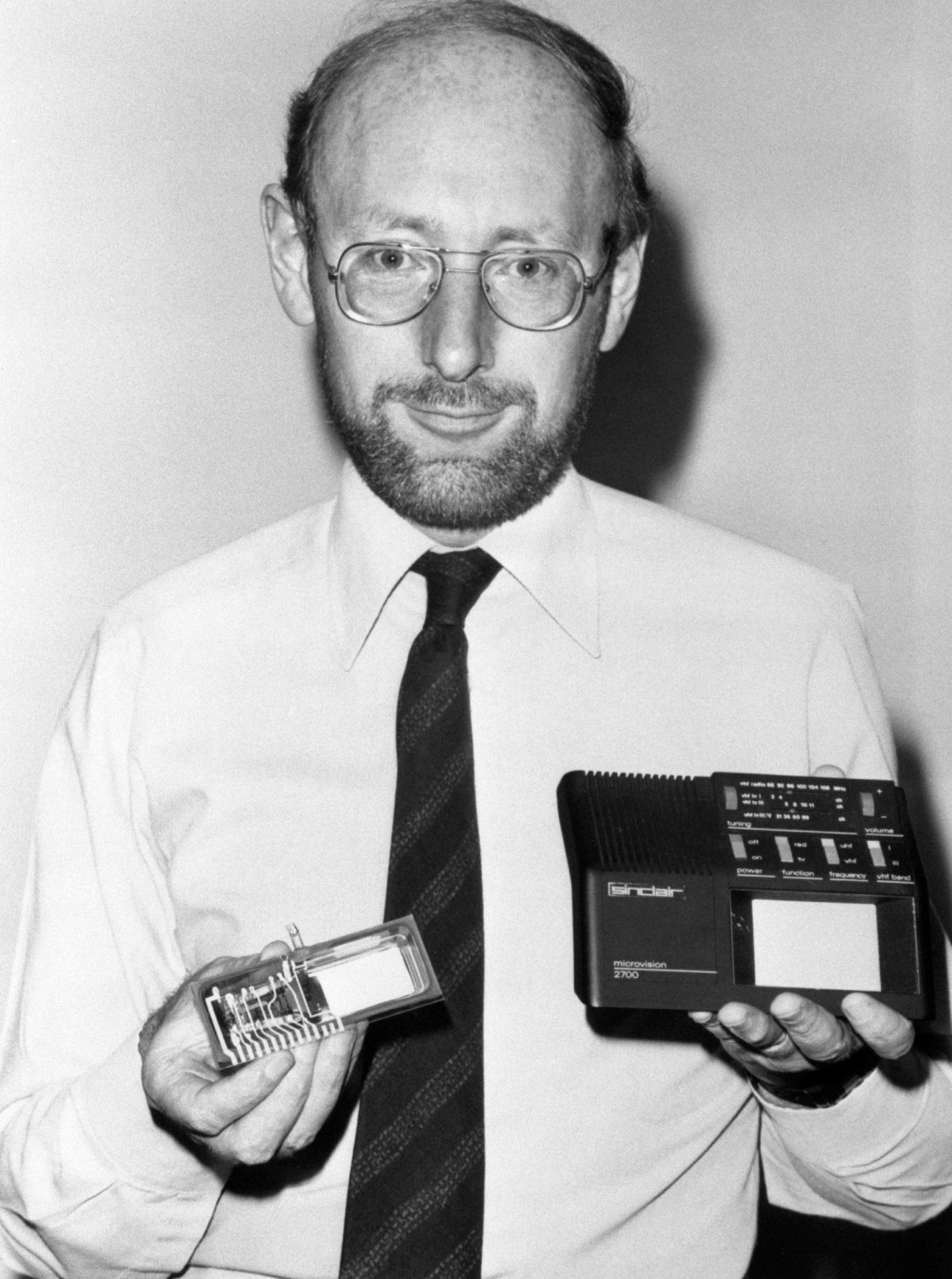

Thanks to the quality of the workforce, however, Timex found sub-contract work in new technologies in the 1980s, such as the Nimslo 3D camera and Sinclair computers.

What happened 40 years ago?

The saddest day in Dundee’s industrial history unfolded when Nimslo decided to cease production of their 3D camera at the Timex plant at Milton of Craigie.

A spokesman for Nimslo said: “There is considerable regret on the part of Nimslo, I can assure you, but it is a question of market demand.

“The camera has to be sourced in a reliable way.”

Timex management also decided to bring to an end their traditional watchmaking operations, which made the company world famous.

Timex started a formal consultation on 1,900 redundancies.

The job cuts were virtually half its workforce and would leave 2,300 employees.

In a plea to the workforce to accept the job losses, Barrie Lawson, the company’s director of UK manufacturing, said: “If conditions are not achieved without work disruptions then total closure could well result.”

To complete Dundee’s worst-ever day on the employment front, Bett Brothers Ltd announced that they were seeking 105 redundancies over the next 13 weeks.

The affected factories at Timex were at Dunsinane Avenue and Milton of Craigie.

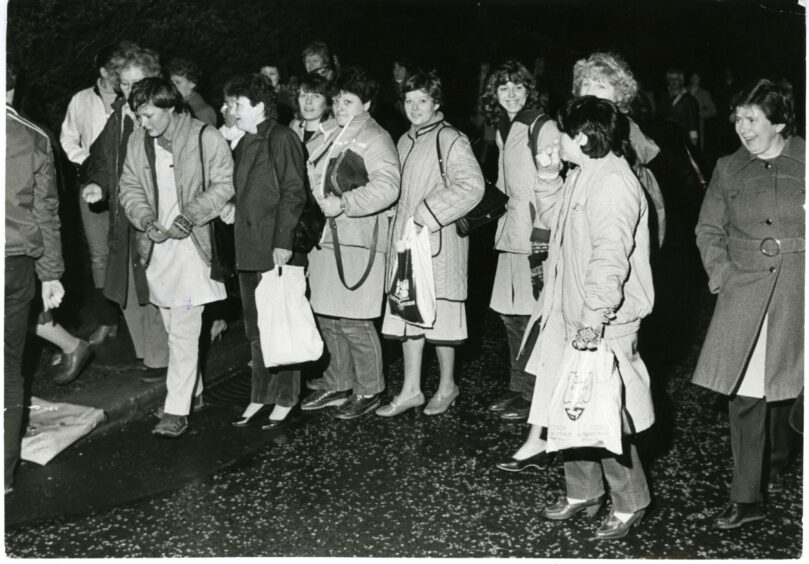

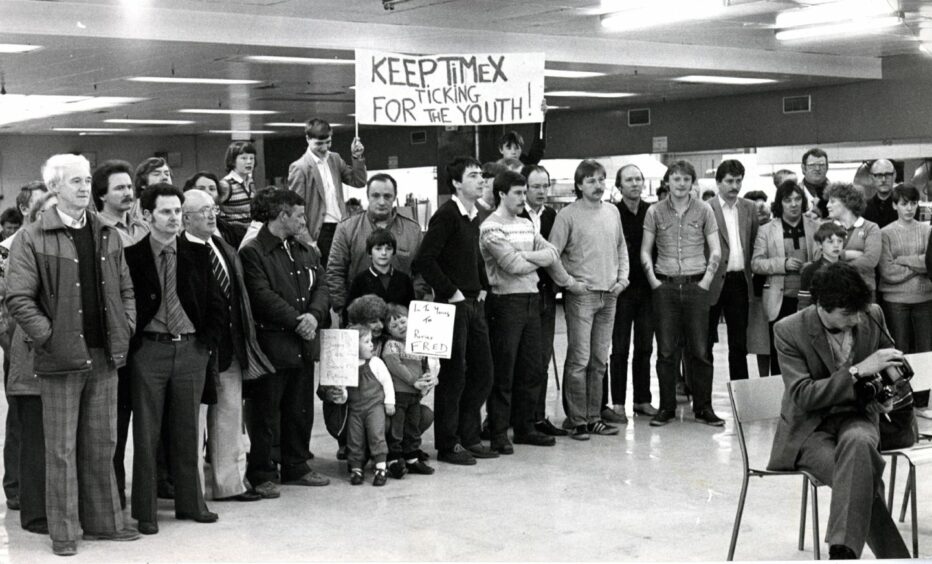

A mass meeting of 4,000 Timex workers was then held at the Caird Hall on January 12 and they voted overwhelmingly to strike if compulsory redundancies were imposed.

Timex was assembling Clive Sinclair’s pocket TVs and his ZX Spectrum.

He said: “If the threat of strike action is not removed in the discussions between the management and unions, and a full strike appears inevitable and affects our production, we will move our business elsewhere, probably permanently.

“The withdrawal would also affect the future products which we also had planned to manufacture at Dundee and which would have provided considerable additional employment.

“We would take this decision with great regret in view of the excellent relationship developed with Timex over the past two years and the high quality and high levels of production achieved by its employees.

“However, in a rapid-growth business such as ours, we cannot afford any disruption to our production which would affect our position in highly competitive world markets.

“Accordingly, we have identified alternative sources of supply which will ensure complete continuity of production levels to all our customers.”

Trade union leader Harry McLevy was someone who did not suffer fools gladly.

“So far as industrial relations are concerned he is better keeping his mouth shut,” he said of Mr Sinclair.

“Every time he opens his mouth and threatens us that the future he is offering us is only if we accept 1,900 redundancies means that we are looking down the barrel of a shotgun and we are not prepared to live like that.”

Margaret Thatcher intervened

From the beginning the unions alleged that the company were transferring watch production to the Timex factory at Besançon in France because of massive subsidies offered by the French government which amounted to £12 million in grants and £33 million in loans.

Timex stated that job losses at Dundee did not result from the transfer of work to France and that, on the watch side, the redundancies had been caused by major rationalisation in the face of the dramatic decline in demand for the product.

Dundee District Council’s Labour administration voted through a proposal to give £10,000 to the trade unions to fight the 1,900 redundancies at Timex.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher wrote to Timex owner Fred Olsen on February 16.

“I am writing to you personally about the future of the Timex operation at Dundee because I believe that this is a case of great importance to the UK economy,” she stated.

“Until a few months ago we regularly pointed to Timex in Dundee as a model example of a company which, faced with the common problem of a declining market for its products, embarked upon a radical programme of diversification into new, high technology products.

“We were proud that the government had been able to help your company put this programme into operation.

“You can imagine therefore the concern when, in addition to the 1,200 redundancies announced as a result of phasing out the manufacture of traditional mechanical watches in Dundee, the 3D camera contract was terminated mutually by Timex and Nimslo, with the loss of 700 jobs.

“While the scale of redundancies on the watch side was clearly very severe, the loss of Nimslo was a serious blow to Dundee’s reputation.”

Mrs Thatcher said a “good deal of this damage” was repaired by the satisfaction with Timex performance expressed publicly by major customers such as Sinclair and IBM.

She highlighted assurances given by the firm that it was willing to consider locating not just new products at the Dundee factory but also research and development work.

“I understand that the company’s decisions on the watch making side result from the decline in the world market for mechanical watches,” the Prime Minister went on.

“But I want to assure you that the steps which you are currently taking to secure the electronics business, together with any further moves which you might be considering to establish a platform for future growth in Dundee, will have our full support.”

Timex management said there had been a reasonably significant response from employees to the offers of voluntary redundancy and early retirement.

Of the 1,900 redundancies originally announced 1,700 were secured voluntarily.

The remaining 200 would be compulsory redundancies.

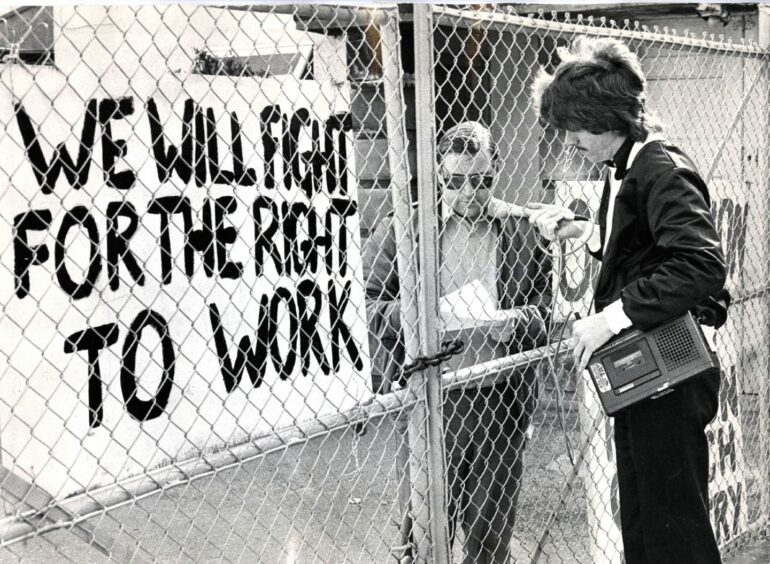

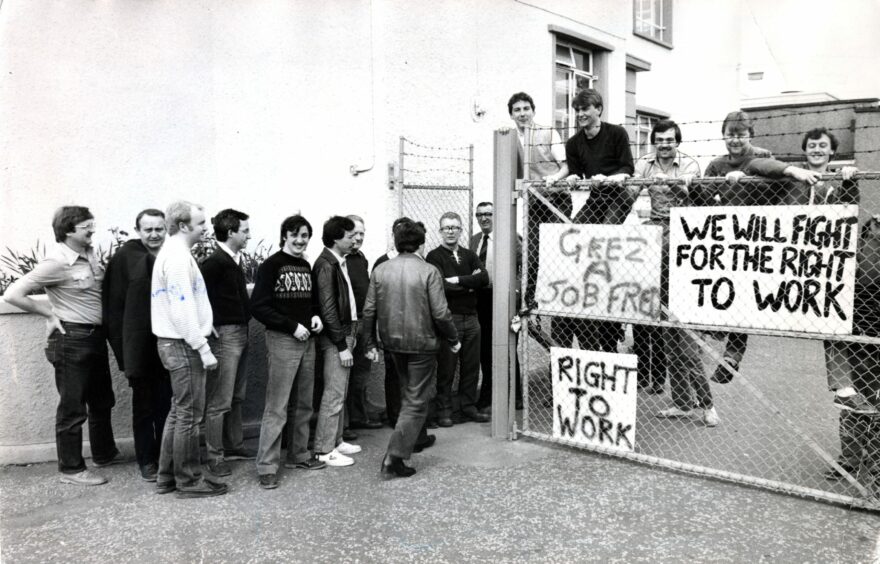

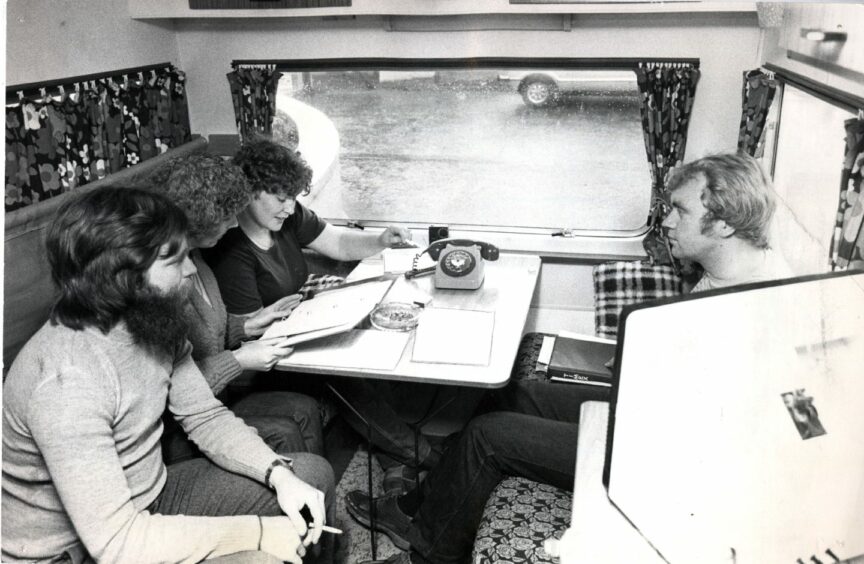

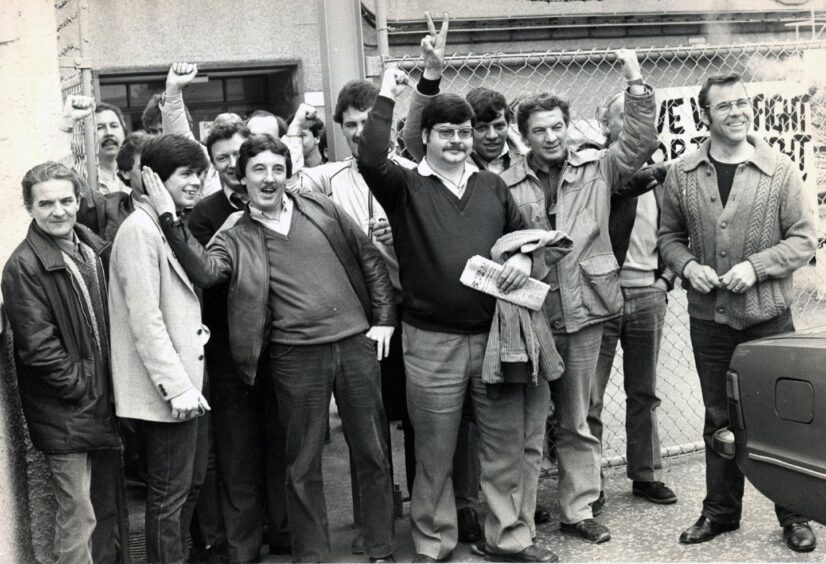

On April 8 the Milton workers resisted compulsory redundancy by occupying the plant.

Willie Leslie, a shop steward, said: “Over the past 90 days we have exhausted all possibilities available to us.

“Our backs are to the wall and we now have no option other than to take the present industrial action.”

In the course of the six-week occupation it became clear that watch-making could not be preserved and 300 further redundancies were announced on May 6.

The further 300 posts were as a result of lost business from the sit-in.

Those involved shifted their goal to securing improved exit terms and on May 18 the workers agreed to accept an agreement and go back to work.

Timex lifted its court action to repossess the Milton of Craigie building.

The agreement accepted both the initial 1,900 redundancies announced on January 10 and the further 300 announced on May 6 as a result of lost business.

But the sun was setting on Timex.

The Milton of Craigie plant was slowly wound down, closed, sold-off and bulldozed in 1988 and Dunsinane was closed and torn down in 1991.

Timex closed its doors for the last time on August 29 1993, following six months of bitter industrial unrest and battles on the picket lines.

Conversation