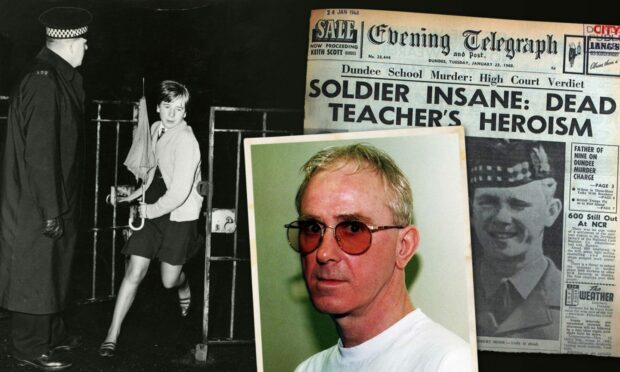

Murderer and rapist Robert Mone made sure he had the last word after being declared insane at the High Court in Dundee on this day in 1968.

The 19-year-old looked down at his shoes and muttered: “Good for you,” as Lord Thomson ordered him to be detained without limit at the State Hospital at Carstairs.

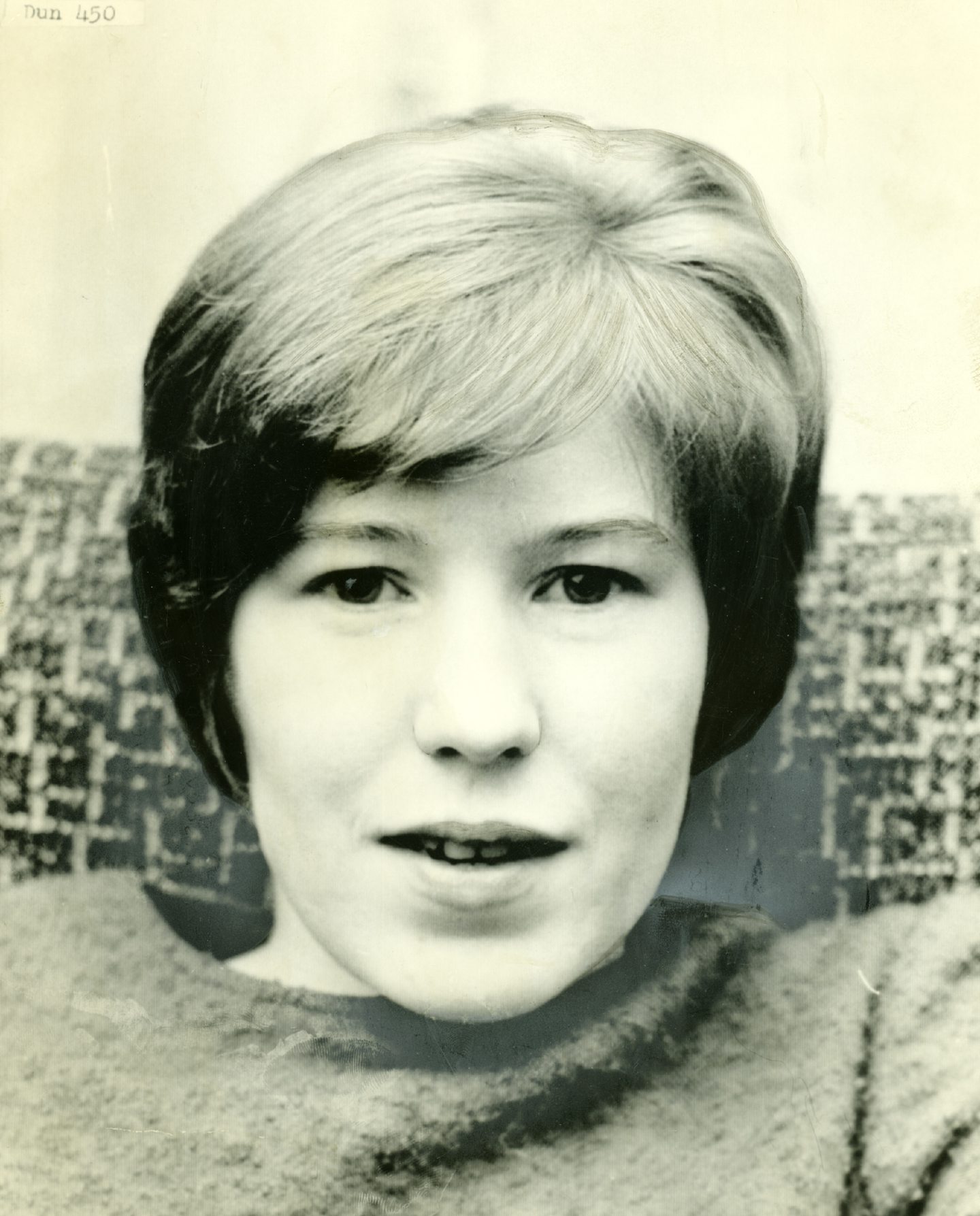

Mone was charged with the murder of pregnant teacher Nanette Hanson at St John’s High School in Dundee on November 1 1967 and the rape and assault of two young girls.

Mone had been expelled from St John’s in 1964.

He decided to join the British Army and was posted to West Germany.

Mone was dressed in his Gordon Highlanders uniform and armed with a shotgun when he entered 26-year-old Mrs Hanson’s class of 11 girls aged between 14 and 15.

Mone then asked to see a former acquaintance called Marion Young, an 18-year-old Dundee student nurse he had met four years previously at a youth club.

She volunteered to go into the classroom and attempt to talk Mone out of murder.

The two women persuaded Mone to let the girls go, but, as Mrs Hanson lined up to leave, he told her: “Not you. You’re not going. I want you here”.

He asked her to turn away and shot her in the back at 4.30pm.

The first witness in support of Mone’s plea of insanity was Doctor Peter Aungle, the consultant psychiatrist and physician superintendent at the Royal Liff Hospital.

Dr Aungle said he had carried out a number of psychiatric examinations on Mone.

The Courier reported: “He had also made inquiries into his background by interviewing relatives and persons who knew him.

“He had had access to reports from schools where he had been and from Army units with which he had served.

“From his observations of the accused’s behaviour, of his grossly incongruous emotional reactions and of his impaired powers of coherent thinking, he had formed the opinion that he was insane and would not be able to instruct his defence or follow the court proceedings.

“Dr Aungle thought the form of insanity was schizophrenia and in assessing his state of mind at the time of the alleged crimes one had to consider the probable duration of this condition.

“Indications were that this condition had developed insidiously over a period of approximately two to three years.

“On the basis of the history available, the bizarre character of the crimes and the accused’s account of his motives, Dr Aungle was of the opinion that Mone was also insane at the time of the crimes with which he was charged.

“He was further of the opinion that his mental disorder required a hospital course of treatment, and in view of the dangerous, violent and criminal propensities, such treatment should be in a state hospital.”

Dr James Fleming McHarg, consultant psychiatrist and lecturer in clinical psychiatry at Dundee University, said Mone’s thought processes were “seriously disturbed by reasons of schizophrenic psychosis” and he was not able to instruct his defence in respect of any of the charges or to follow the proceedings in court.

Dr McHarg said Mone was insane and unfit to plead to any of the charges, and, at the time of the alleged crimes, he was already suffering from schizophrenic psychosis “and could not appreciate his acts were wrong”.

‘I tried to find a pulse…’

Advocate depute Donald Macaulay paid tribute to the courage and heroism of Mrs Hanson and Marion Young after Mone had been led below from the dock.

Marion spoke afterwards about Mrs Hanson’s final moments after both women had been praised by Mr Macaulay for “their extraordinary calmness, courage and heroism”.

She said: “Mone had closed most of the curtains so that people outside couldn’t see in.

“But a curtain at the end was still open.

“He told Mrs Hanson: ‘Go and close that curtain’.

“She turned round and walked towards the window. The next second there was a bang.

“Mrs Hanson moaned and stood for a few seconds before falling to the floor.

“I suppose I was stunned for a moment or two then I ran to Mrs Hanson.

“I tried to find a pulse – it was very weak. I went down on my knees and pleaded with him: ‘You’ve got to help me’. He was laughing then he said: ‘Do what you like’.

“But by now I didn’t care. I pulled away the barriers at the door and shouted for a stretcher. I ran back and shouted to him but he just sat there and laughed – not normal laughter, but crazy, almost hysterical laughter.”

The siege which had lasted nearly two hours ended when police with dogs moved in through the open door and arrested Mone.

Mone, together with fellow patient Thomas McCulloch, slaughtered their way out of Carstairs on November 30 1976, leaving a hideous trail of murderous destruction.

Nurse Neil McLellan, 46, and patient Iain Simpson, 40, died under ferocious axe blows.

Simpson even had his ears cut off.

They went on to kill a young policeman, George Taylor, 27, maimed two workmen and held a family hostage in their home before fleeing to England, where they were arrested.

After they were recaptured, both were sent to mainstream prisons for security reasons by a judge who ruled they should remain in custody “for the rest of their natural lives”.

His partner in crime, McCulloch, was released on licence in 2013 and set up home with a divorced mother-of-three in Dundee.

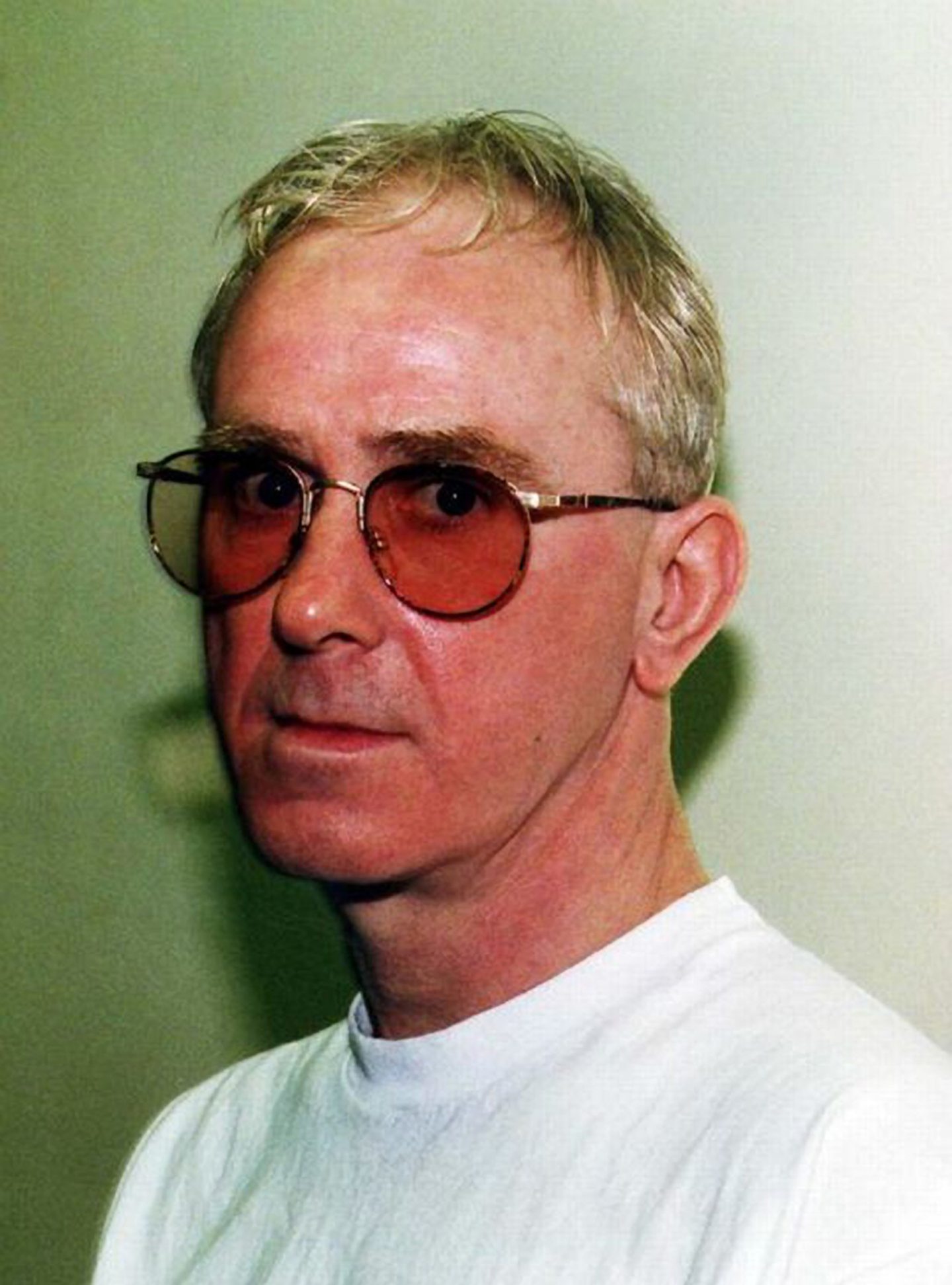

Now aged 74, Mone remains in Glenochil prison.

Mone knew exactly what he was doing

Mone broke his 30-year silence over the St John’s High School siege in 1997 and cockily admitted that he pulled the wool over everyone’s eyes.

He said: “I knew what I was doing.

“But I didn’t want to plead guilty. After it happened I just wanted everything to stop.

“It was all over for me now and I knew that I didn’t want to go to court.

“I just wanted everything to stop.”

So why did Mone decide to go to St John’s with a gun?

He said he couldn’t really explain why but had decided “that this was it”.

Mone bleated: “I got my gun and covered it in brown wrapping paper and went towards the school. I can still remember distinctly going into the school.

“I hadn’t chosen any class or anything. I just started to walk up the stairs.

“Every step I took I remember wishing that the steps would go on forever because it was getting close to the time that I would have to do something.

“I knew that when the steps came to an end I would have to go into a class and I went into the class that faced the top of the stairs.

“It was Nanette Hanson’s class.

“I barricaded the door with some tables. I remember the feeling of power I had because everyone was scared of me.”

Mone described how he felt immediately after the murder.

“There was a terrible tightness in my head, then there was this overwhelming tiredness, real lethargy. I’ve never felt so tired.

“I put the gun down then sat down.”

It was his last day of freedom.

Life in prison, however, has been a more humane sentence than the one Mone handed down to Mrs Hanson, who died a heroine’s death to save her pupils.

Conversation