Blizzards buried villages, farm animals died in droves and roads and railways were impassable during the Big Freeze of 1963.

Dubbed ‘the winter to end all winters’, roads and railways were put out of action and phone lines went down when people desperately needed them.

Temperatures in Scotland dipped to near -30C.

Lorries on the motorway had fires lit under their fuel tanks to thaw the diesel.

By the time March arrived and things eased – March 6 was the first morning without frost anywhere in the UK – a quarter of the nation’s sheep had perished.

When did the Big Freeze start?

Fog and ice had already caused chaos when snow began falling on December 24 to give Glasgow its first white Christmas since 1938.

Initially it was welcomed particularly by children who saw it as a bit of holiday fun but soon the mood turned to despair.

On Boxing Day, the 1.30pm Glasgow to London express, continuing on through frozen points and warning signals in heavy snow, ploughed into the back of a stationary train near Crewe.

The rear carriages of the train to Birmingham were crushed and 18 people lost their lives, with another 30 badly injured.

Throughout January, February, and the early days of March, the weather continued to play havoc.

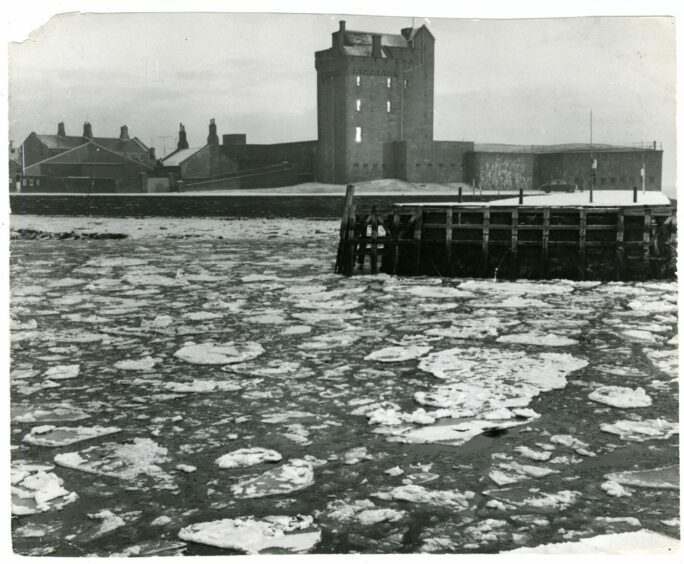

For the first time in many years ice was a navigational risk with Broughty harbour beset by ice and the sea off the Ferry beach looking like a scene from the Antarctic.

Transport was a no-go as trains froze, along with the diesel in buses and lorries.

Residents couldn’t even enjoy a cup of tea as milk bottles froze solid.

The cream erupted and used to rise up frozen out of the bottles like icicles.

Water pipes were frozen solid for weeks at a time which meant that people had to use buckets to collect drinking water.

Entire houses were buried under the snow and every part of the country was hit by the freak conditions.

There was the solace of TV and radio but in some areas communications were cut with phone lines down.

British football was brought to a virtual standstill by the unprecedented cold snap, and between January and March, hardly a ball was kicked in anger.

Dundee did progress to the second round of the Scottish Cup with a 5-1 win on January 12 at Inverness Caley before the football programme was completely wiped out.

But at least the players could enjoy a hot bath after the game – Caley’s right-back Robert Glennie, a plumber by day, de-iced the Telford Street Park pipes with his blowtorch beforehand.

As well as disrupting services, the snow brought mishaps and accidents.

Fife native Patrick Patterson, 45, was killed when his car was struck by a lorry on the main Aberdeen to Stonehaven road near the village of Muchalls in Aberdeenshire.

Mr George Kidd from Dundee was driving the lorry travelling in the opposite direction which was thrown into a broadside skid and collided with Mr Patterson’s vehicle.

The car was completely wrecked but the lorry was only slightly damaged.

Mr Kidd told the P&J: “My mate and I got out and ran over to the car to get the driver out while another motorist phoned for a doctor.

“We eventually got him out but he was already dead.”

Mr Patterson worked for George Mellis & Son wholesale grocers in Aberdeen and was a popular amateur singer and entertained at charity concerts in the Granite City.

Just when it felt like the perishing conditions couldn’t get any worse, the mercury slid even further down the scale on January 18.

It seemed that the freeze would never end.

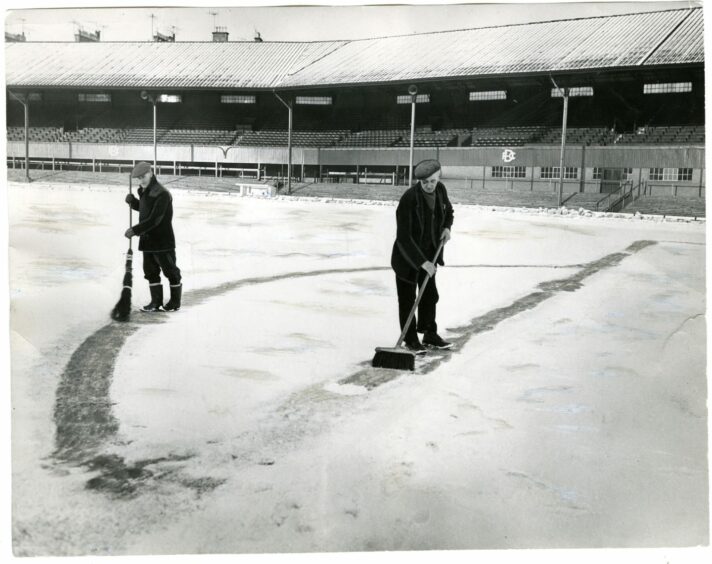

Burning the grass at Tannadice Park

Various ideas were tried to beat the freeze notably at Tannadice Park.

Manager Jerry Kerr and the Dundee United board moved heaven and earth to try to make the pitch playable for their Scottish Cup tie against Albion Rovers which was scheduled for January 26.

At first fire braziers were tried before William Briggs & Sons, road makers at the Camperdown Refinery at Dundee docks, brought in a tar-burner to melt the Tannadice ice sheet which also burned off all the grass.

Several lorry-loads of sand were then spread over the pitch and with their pitch increasingly appearing like a desert wasteland, legend has it that this was the time when United supporters became known as the Arabs.

One by-product of the arctic conditions in 1963 was the setting-up of the Pools Panel, which allowed the punters to have a flutter with their coupon, no matter the weather.

In total the panel of four famous ex-footballers determined the results on five Saturdays during the ‘Big Freeze’ and were to become a regular feature in winters to come.

A ‘creeping thaw’ set in towards the end of January, but it was short lived.

Any hopes the weather would improve in February were dashed.

Major roads including the A9 and A90 were blocked during blizzard conditions.

People in parts of Scotland were left stranded in trains with some children forced to remain overnight in snowbound schools.

Meanwhile, the prolonged interruption to the football programme had provided some time for measured debate.

The future of the Scottish game had returned to the agenda as a result of the weather.

All 37 Scottish League clubs received a circular outlining a scheme for summer football which went to a secret vote in Glasgow on February 25.

The proposal was that the season would run from March to the end of November with a break of two or three weeks in July.

Scottish Cup ties would be brought in much earlier than usual at the beginning of May with the final at Hampden on a Saturday in June.

The League Cup would be switched from the beginning of the season to nearer the end with the final in late November.

Scottish League clubs voted 25 to 12 to stick with the status quo.

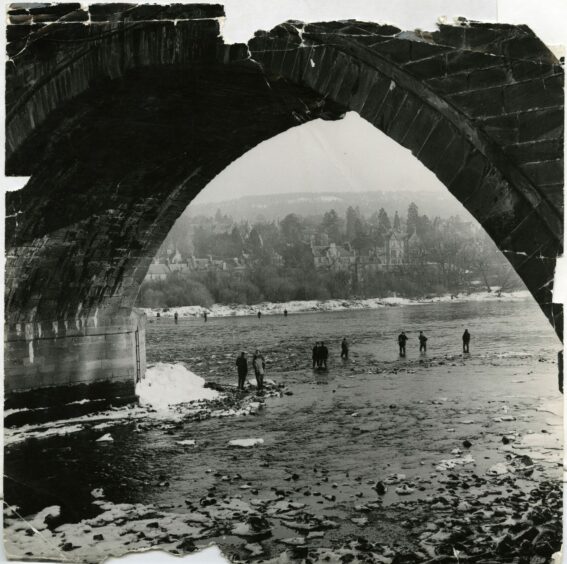

Walking on the River Tay in Perthshire

On February 26 1963 during the Big Freeze, two Stanley men became the first people to walk across the frozen River Tay since 1898.

Alec O’Brien and brother-in-law Ian Smith managed the feat at the picturesque Perthshire village of Burnmouth.

They abandoned an attempt to repeat the crossing on bicycles a few days later.

“It would be too risky,” said Alec.

“We were lucky to catch the right conditions on the first attempt.”

A Siamese cat decided to make a similar attempt but was marooned on a tiny island in Perth.

The cat, Thai-Ming, which was owned by John Harrison, manager of the Cross Keys Hotel in Bridgend, walked daintily over the ice until she reached Stanners Island.

The feline adventurer almost lost one of her nine lives and got stuck there for almost 24 hours when the ice started to break up.

Thai-Ming eventually returned home soaking, wet and hungry but was none the worse for her escapade.

It wasn’t until March 6 when there was finally respite and the thaw began.

But melting ice saw torrents tear through communities.

Rapidly melting snow on fields surrounding Brechin saw water cascade through the town.

Water six inches deep rushed down Cookston Road and burst through manholes near the fire station, marooning it on its own island.

The 10-feet wide flood river eventually hit the gasworks where firefighters spent three hours pumping away four feet of water.

However, tonnes of coke were washed away and people at the foot of Witchden Road were collecting it in buckets – until a gusher of water shot up and burst the street open!

At North Port distillery work was brought to a standstill when dam levels breached the 100% mark and water was two feet deep both inside and outside the building.

Thankfully things began to settle down but the bitterly cold and unsparing winter of 1963 is still remembered to this day by many Scots of a certain vintage.

Conversation