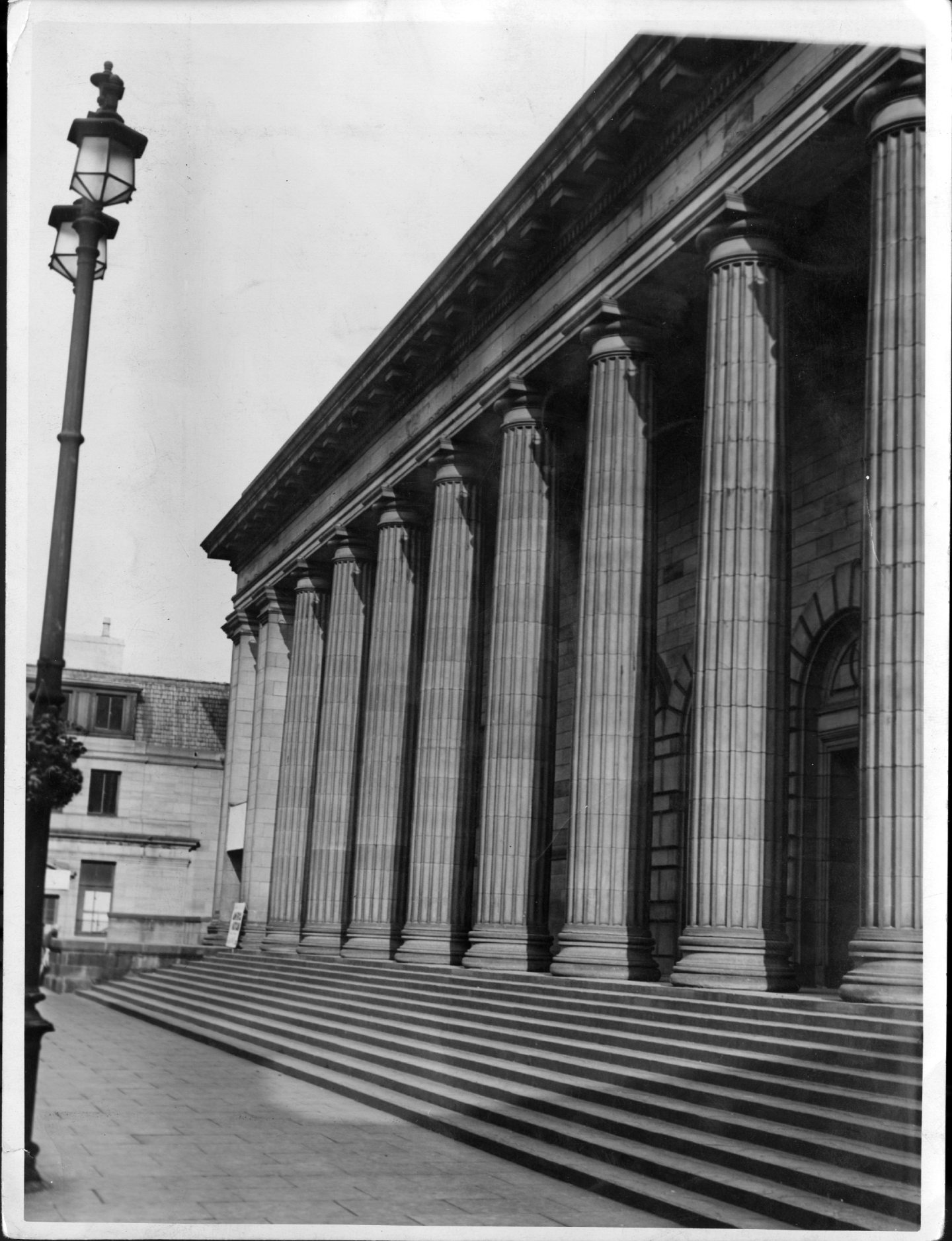

The Caird Hall has been a dominant feature of Dundee’s City Square since it was first opened in 1923.

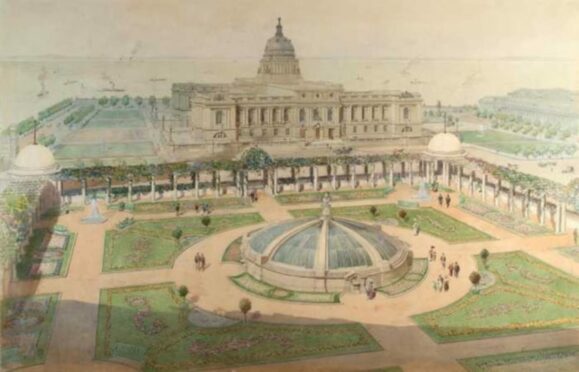

Plans for a new, modern building near Crichton Street were first submitted by the city architect, James Thomson, in 1910.

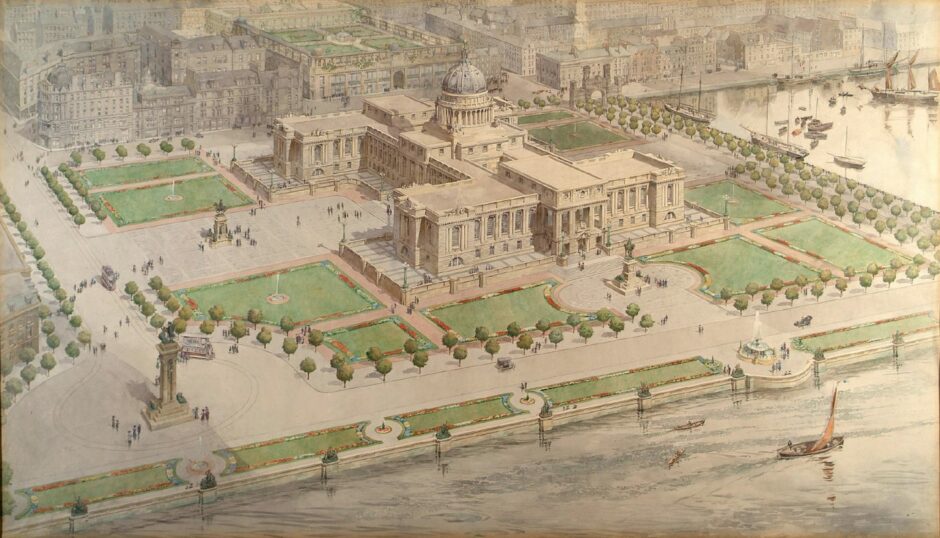

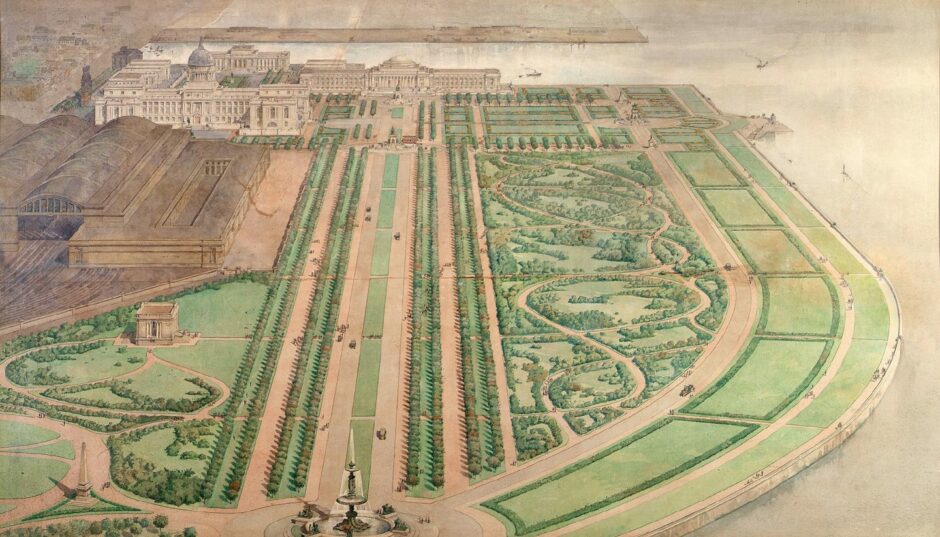

At that time, the plans proposed a Civic Centre to stand at the harbour – where the V&A museum is currently located.

When Sir James Caird offered to fund the project, he made adaptations to the architectural designs and these new plans eventually created the Caird Hall we know today.

However, several features from Thomson’s original designs remain in place.

Dundee University’s Kenneth Baxter tells us what inspired his plans.

The Caird Hall

Despite Dundee city centre undergoing radical architectural changes in the 1870s, this wasn’t enough for its people, who wanted to see further modernisations.

Calls were made to upgrade the harbour, which was falling into disrepair, alongside the Overgate and Crichton Street.

The area linking Crichton Street to the market included some of Dundee’s oldest buildings and, by the 20th Century, had become slum housing.

This was the major entry point for visitors to the city and its citizens did not want it to be a visitor’s first impression of the city.

It was time for redevelopment.

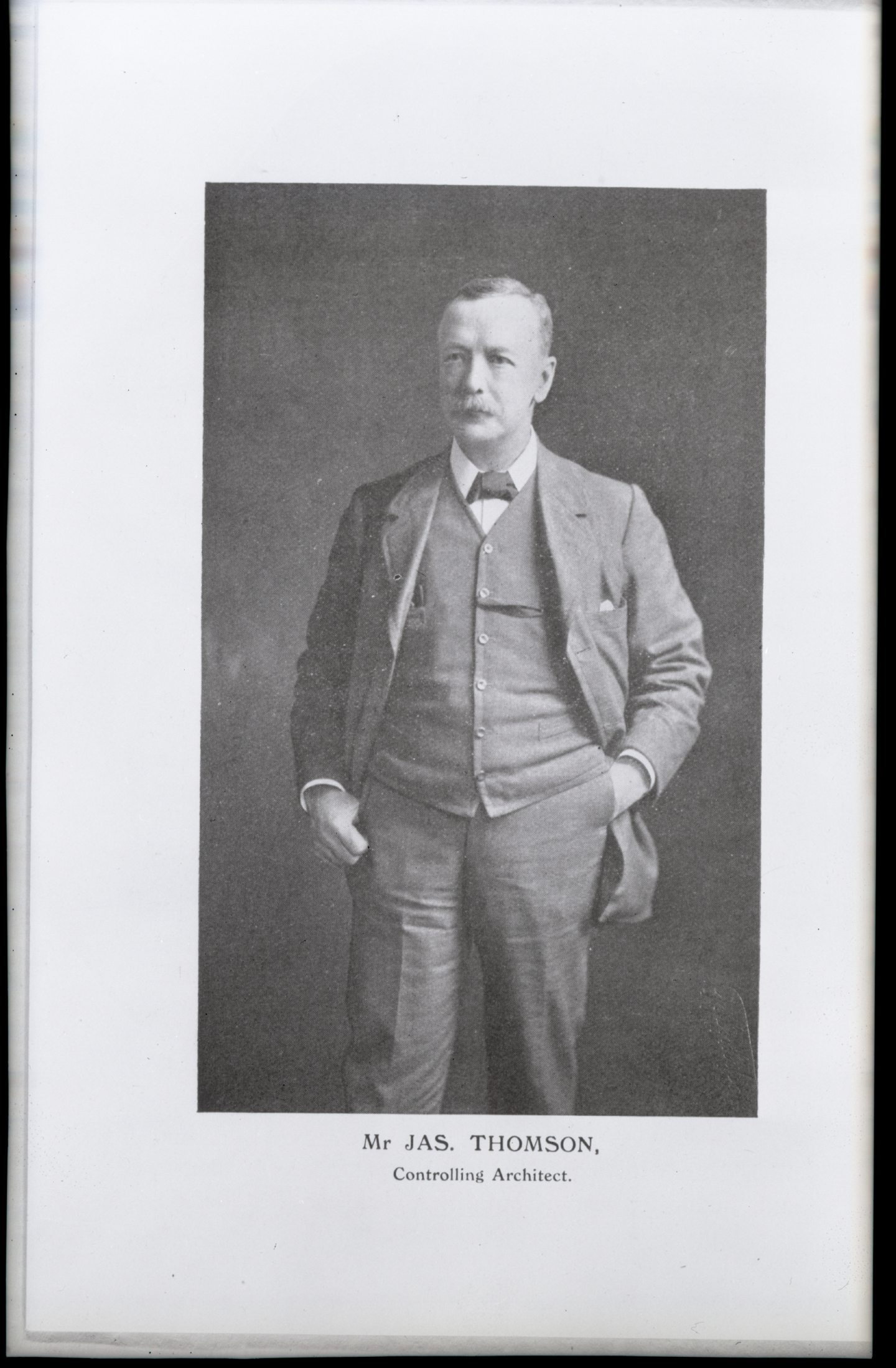

James Thomson submitted a report to the council in 1910.

Thomson had been the city’s architect since 1906 and drew up several plans on how to redevelop these areas of Dundee.

A man who was years ahead of his time, Thomson was determined to make Dundee beautiful.

Kenneth said: “Thomson’s report is one of the most interesting documents in the city of Dundee.

“He proposed really radical change for the city.

So this is what Dundee could’ve looked like – it would’ve been radically different.”

“He wanted to completely clear the area behind the town house and a new public market would be built in its place.

“It would stretch right down to Shore Terrace, and the old green market would’ve been eradicated.

“However, the biggest change of all would be down at the shore.

Thomson’s plans

“Docks would be filled in, and a new great building – which, at the time, he called the Civic Centre – would be erected.”

Thomson’s plans for a civic centre had come from his travels around Britain.

He had seen St Paul’s Cathedral in London and it could well have inspired him to construct plans for the domed roof.

Kenneth added: “It seems probable that St Peter’s Basilica, in the Vatican City, could’ve also inspired his drawings.

“Where Thomson planned to have the Civic Centre is now near to the location of the existing V&A museum.

“So in some ways, Thomson wanted an iconic building down there, he’s now got it – even though it was more than 100 years after his plans were first introduced, and in a very different format.

“Thomson ultimately recognised the importance of Dundee’s shoreline, and is why he thought it was a good idea for the city to have a new, modern building like this down there.

“The buildings at the end of the Overgate between the Overgate and the High Street, and the Nethergate, were also going to be taken down.

“The city churches would then face on to the western end of the High Street.

“Isolating them in this way would give them a grandeur that they’ve never really had in Dundee.

“In front of this there would be a park, with fountains and statues.

“The Overgate itself would be widened, buildings would be removed, and tram lines would be added.

“Thomson was a strong advocate for trams as a form of public transport and was keen that the network in Dundee would expand.

“So this is what Dundee could’ve looked like – it would’ve been radically different.”

But there was a problem.

How would these new plans be funded?

Finding the funds

Kenneth added: “Thomson’s plans were so grand that the City Council were never going to be able to fund it on their own.

“They were also under pressure to do something with the city’s housing conditions – and that was a political priority over the grandiose building projects.

“They did eventually get a new civic building – but it wasn’t quite the building Thomson planned.”

Sir James Caird approached the City Council and offered to donate money for a new City Hall.

Caird was one of Dundee’s most successful entrepreneurs and invested many of his profits back into the city.

However, his funds meant that he was given some input into the designs for the building.

As the City Architect, Thomson remained as a consultant on the project; however, several of his original designs were heavily modified.

Work begins

Work on the Caird Hall officially started in 1914.

The foundation stones were laid on July 10 by King George V and Queen Mary and can still be seen at the Caird Hall today.

However, Britain became involved in the Great War shortly after the work began.

After several of the workers were enlisted, construction work came to a halt on Dundee’s newest building.

During this period, Thomson inspired the creation of the Kingsway bypass.

He was determined that the new designs would cut down on congestion and make the city a greener place.

He also designed Logie and Craigiebank housing estates in 1917 and 1918.

Logie later became the first district heated housing scheme.

Construction began on the Caird Hall again after the end of the war.

The new building was opened to the public in 1923.

Kenneth added: “Caird had died by this point – he never got to see it finished and opened.

“However, he did predict that the building would eventually become part of the new City Square – which it did.

“As for Thomson, while some of his designs were changed in the process, the pillars at the front of the building were likely inspired by his original sketches.”

Thomson saw the new City Square and the Caird Hall completed and felt that the project was one of his proudest achievements.

He was walking through the finished Caird Hall on November 10 1927 when he collapsed in one of the hallways.

Simon Fraser, a long-serving councillor, and the Lord Provost Sir William High were in the Lord Provost’s office when they heard what had happened.

Both went to attend to Thomson, and Fraser was holding him when he died.

Thomson was 76.

At the time of his death, Thomson was engaged in some of the plans to erect an East Wing to the hall.

His funeral took place in Balgay Cemetery on November 14 1927.

Conversation