Wallace Craigie Works, known as Halley’s Mill, was a Dundee landmark and employed countless generations of workers through the decades.

At one time the bustling linen mill employed more than 3,000 workers from Tayside and Fife and was instrumental in Dundee’s success in the jute industry.

However, changing times forced the business to close its doors for good in 2004, before the Blackscroft building was controversially razed in 2018.

As work starts at the site ahead of an application to build 130 flats, we’ve opened our archives for a look back at when the curtain came down on what was an iconic building.

The story of Halley’s Mill starts in the 1800s.

In 1822, the linen trade in Dundee employed around 3,000 people.

By 1831, that number had risen to 6,828.

Linen was a steady source of commerce for Dundee businesses compared to its jute, which fluctuated in price over the years.

A guaranteed income, then; Halley’s Linen Mill was built in 1834.

The factory was a partnership between three local flax manufacturers – Robert Brough, James Gilroy and William Halley.

It was Halley’s name that would be painted on the front of the building, in bright yellow paint, which, over time, would become iconic.

The partners rented the land that the works were to be built on from George Constable, who was a friend of the novelist Sir Walter Scott.

The finished mill opened in 1836

The building was eventually built using stone from the adjacent quarry.

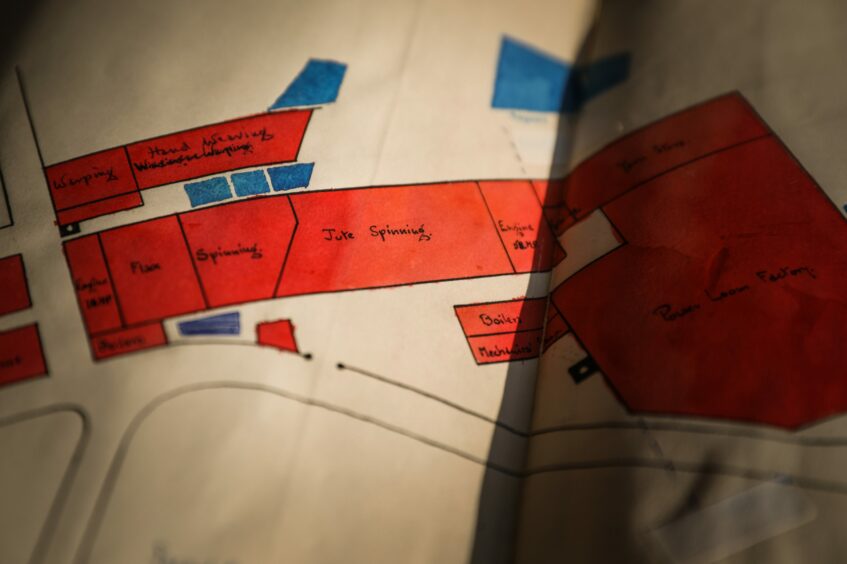

The finished mill opened in 1836 and started out as a flax manufacturer, initially running a handloom factory in the city centre.

It was the first fire-proof mill in the city, although to begin with, only its roof was insured.

At the time Dundee was producing coarse linen.

In the early 1800s it exported sailcloth, bagging and cheaper shirting to frontier settlements in Canada and North America.

As markets changed, the trade moved south to the slave plantations of the New World.

Vast quantities of Dundee’s linen was used to clothe slaves on plantations in the slave capitals of Savannah, New Orleans, Mobile and Charleston.

In a time when messages took three weeks to cross the Atlantic, communications between the Dundee factories and their buyers were sometimes lost or confused.

Eventually, Dundee realised it was over-producing hemp and sending too much cloth to New York.

This was the city’s first challenge in the industry – but it wouldn’t be the last.

Triumph and tragedy for Halley’s

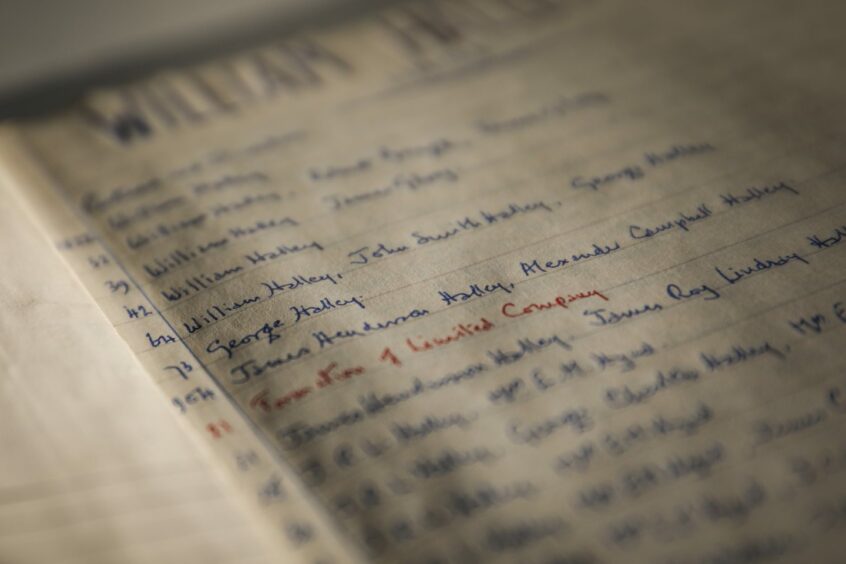

Halley’s sons, James Henderson and Alexander Campbell, took over the business just before the First World War.

When the war broke out, the factory had a period of success as it worked at full capacity to make jute sandbags.

However, after the war, the Depression caused a drastic downturn in fortunes.

Two devastating fires in the ’40s and the ’50s also hampered trade.

The works were rebuilt in the 1960s and operated as a factory producing backing cloth for the tufted carpet industry.

On account of its success, the Halley family decided to set up another mill in Perth.

However, fortunes were turning once again when the ’70s rolled around.

That year saw W G Grant & Co Ltd close their factories in Dundee and Carnoustie.

T L Miller & Co Ltd in Dundee also closed, as well as Douglas Fraser Sons Ltd in Arbroath.

The Halley family were determined to persevere and decided to modernise in 1974 with the purchase of 12 new “Gripmack” looms.

These would weave either jute or polypropylene, which is similar to plastic.

However, with jute requirements still declining, that year saw 105 workers in the factory made redundant.

Halley’s Mill stripped back its polypropylene operation in 1982, which resulted in the loss of a further 200 jobs.

The factory finally closed for good in 2004 and the mill fell into a state of disrepair.

After its closure, there were several unsuccessful efforts to redevelop the building into flats and the former mill was eventually placed on the Buildings at Risk register.

On May 11 2018 demolition works by Craigie Estates commenced at the Halley’s Mill site, which were brought to the attention of Dundee City Council.

A spokesman for Craigie Estates defended its actions at the time, saying the building was brought down “on the grounds of public safety”, adding they had applied successfully for a council building warrant.

He said: “We recently had to attend court after someone was caught stealing lead from the building roof.

“This is just one example of the hundreds of incidents which happened on a near-daily basis with people entering the site.

“At the end of the day, we would rather err on the side of caution.

“The building was in a perilous state and children were running all over it.”

Mike Galloway, executive director of city development, said there was frequent

correspondence between council officers and the owners’ representatives late in 2017.

He said: “The information that was provided by the owners’ representatives in the opinion of DCC Engineers clearly confirmed that, whilst defects were present, demolition was not the only option to preserve safety or indeed the building.

“No notification under any of the statutory procedures justifying in detail the carrying out of the works was submitted to the council.”

The council reported the demolition to the Procurator Fiscal, although no charges were brought against Craigie Estates following a police investigation.

The following year a group of fans of the city’s architectural history gathered by the rubble for a memorial event organised through the power of social media.

They arrived at the site of the former mill to lay a large hand-made wreath, which had been constructed from cardboard and hand-sewn burlap jute flowers.

The wreath was also covered with spray paint and read: rest in paint.

It was written in a Georgia font, the same typeface that once featured on the iconic sign adorning the front of the building.

Fast-forward four years and social housing developer First Endeavour is now expected to submit a planning application to build 130 flats on the site in March.

If their plans are approved, building work will begin this year.

Conversation