Kirkcaldy Galleries have been a prominent feature of the town’s landscape since their opening in 1925.

Since then, they have undergone an extensive refurbishment and most recently displayed an exhibition from the town’s own Jack Vettriano.

They are currently displaying The Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist – the oldest artwork in the OnFife Museums’ collection.

We’ve opened our archives for a look at the history of the Galleries that do such a good job of showcasing the history of the town it lives in.

Kirkcaldy Galleries

In the early 1920s, Kirkcaldy-born John Nairn donated a portion of land for the museum to be built on.

The Nairn family were Kirkcaldy’s answer to Andrew Carnegie and his patronage of Dunfermline.

However, the linoleum manufacturers not only provided the town with funds for arts and entertainment, but also with much-needed employment opportunities.

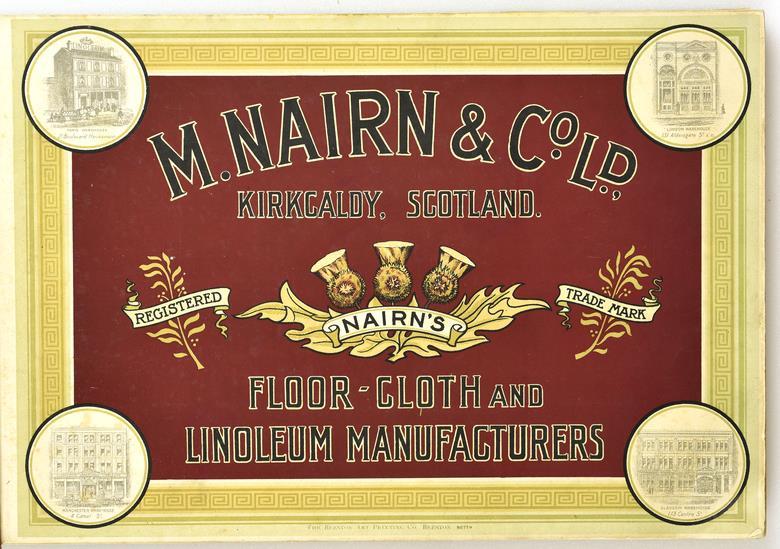

It began with Michael Nairn, who was born into a weaving family in Kirkcaldy in 1804.

Michael joined the family trade and completed his training in Dundee before returning to the seaside town where he was born.

On returning to Kirkcaldy, he set up a small business in Linktown of Abbotshall.

In 1828 he was elected as a burgess of Kirkcaldy. He then moved closer to the centre of town and set up a new business in Coal Wynd, where he made canvas for sails, and backing for the new floorcloth industry.

Michael saw floorcloth as an exciting new venture.

The next closest manufacturing company of the material was in Newcastle, leaving a convenient gap in the Scottish market.

He had a purpose-built factory constructed and was determined it would be a success.

However, it didn’t quite go to plan.

It took months for the raw materials to become the finished cloth.

During those waiting periods, wages and overheads still had to be paid.

Soon it became clear that the business’ financial demands could not be met, and the factory was nicknamed “Nairn’s Folly” by the local population.

Michael died in 1858, aged 54.

What would become of his ventures in the wake of his death?

Michael’s sons Robert and Michael Jr took up the mantle shortly after their father’s death.

They ran the business until the youngest child, John Nairn, joined in the early 1900s.

It was John who carried the business through the First World War, and kept going even after the war brought the death of his only son.

When the fighting ceased, John’s gift to the town was the Kirkcaldy Museum and Art Gallery.

Work on the library began shortly after.

The three new buildings, dubbed Kirkcaldy Galleries, would act as the backdrop to the town’s war memorial.

The cost of the project was estimated at around £80,000.

Opening night

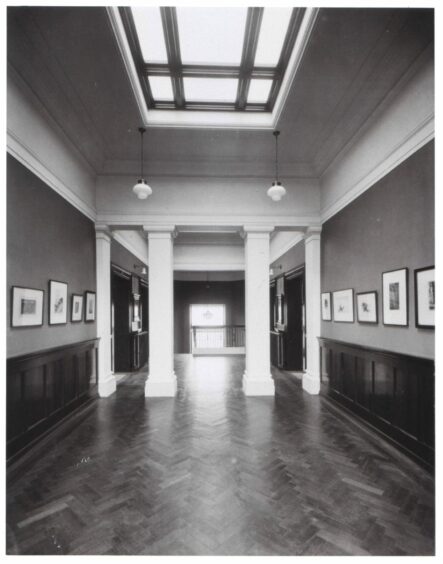

Kirkcaldy Galleries was opened in 1925.

At the time, the Fife gallery promised to “represent the more interesting and distinctive Scottish painters of the past, and of the French and Dutch painters of the 19th century whose work has been most admired in Scotland”.

The National Gallery of Scotland donated works for the opening, alongside the Dundee Galleries.

Among those donated were two detailed paintings completed by Sir David Wilkie.

Wilkie was born in Pitlessie, Fife, in 1785.

After attending school in Cupar, he then went on to study art under Scottish painter John Graham.

The Fife artist eventually became Principal Painter in Ordinary to King William IV and Queen Victoria.

Kirkcaldy Galleries are now home to the second-largest collection of paintings by both William McTaggart and the Scottish Colourist Samuel Peploe.

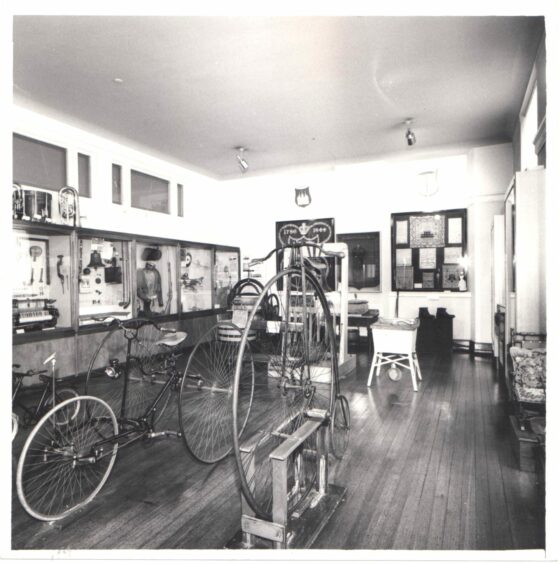

The museum’s award-winning permanent exhibition covering the town’s industrial heritage takes pride of place on the ground floor, harking back to its heritage and the linoleum trade that the Nairn’s were such a significant part of.

Kirkcaldy was once the world’s largest producer of linoleum floor coverings, and the Galleries’ collection includes samples dating back to the 1840s.

In the late Victorian period, Kirkcaldy was a major centre for pottery production.

As a result, the museum now holds over 1,000 pottery objects, including a large quantity of hand-painted Wemyss Ware.

Another major collection covers the long history of coal mining in Fife.

There are also a number of works by the Glasgow Boys.

In 2012 Fife Council undertook a £2.5m refurbishment of the building, which reopened in June 2013.

It now contains an additional children’s library, PC suite, cafe, gift shop, meeting room, and a local family and history room, as well as the original museum and gallery spaces, and library.

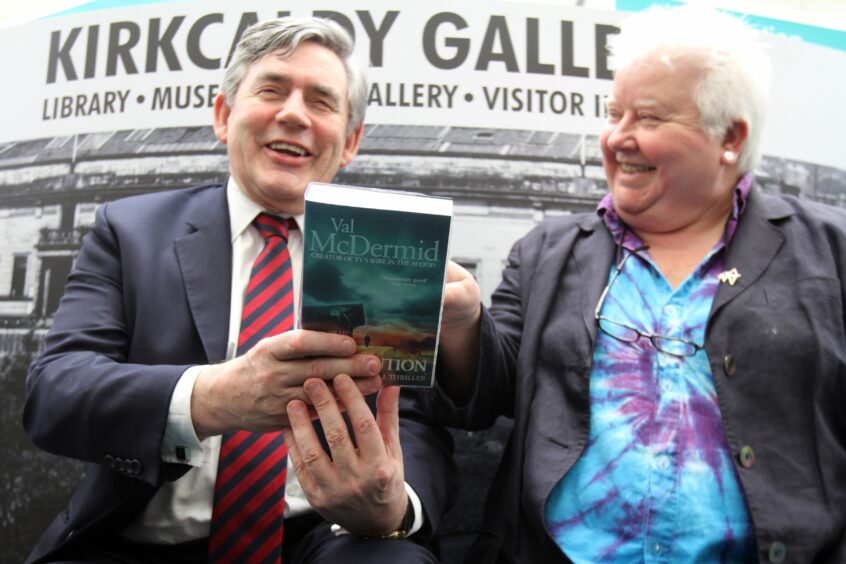

The re-opening was attended by local author Val McDermid, MP and former Prime Minister Gordon Brown, and local artist Jack Vettriano.

The venue then became the first institution in Fife to display work by American photographer Diane Arbus in 2015.

That same year the Great Tapestry of Scotland was on display at the Galleries – and one of its 160 panels was stolen.

The Great Tapestry took more than 50,000 hours to complete and is the world’s longest embroidered tapestry, measuring over 140 metres long.

It was stitched together by over 1,000 volunteers.

The design tells the “story of Scotland” across its intricate panels, and each one covers a different period of Scottish history.

From the Battle of Bannockburn to the reconvening of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, each significant event in Scotland’s history was added to the tapestry.

The stolen Rosslyn Chapel panel was designed by artist Andrew Crummy.

It was never found.

A replacement panel was completed in 2017.

Until the end of 2022, the Galleries were exhibiting a selection of paintings created by Jack Vettriano at the start of his career.

The works were sketches, drawings, and paintings dated from when he first started in his early 20’s.

Several paintings were signed with the artist’s birth name, Jack Hoggan.

Many had never been on public display before.

Currently the Galleries are displaying The Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John the Baptist.

Following an extensive restoration, the painting is now on display at the Galleries – and it’s the first time it’s ever been displayed.

Painted in Florence in the 1520s, it is unknown which artist is responsible for the work.

However, experts from the University of Glasgow – who helped restore the painting – credit the studio of acclaimed Florentine artist Domenico Puligo with the work.

Paint samples taken by scientists at the university helped confirm the date of the work.

The exhibition helps to continue the Galleries’ legacy as a space which can best showcase some of the world’s most notable artworks.

Conversation