Dundee cinema bosses were the tech trailblazers of the early 20th Century whose performance art could match the TikTok videos of today.

As was the practice in those early days, the movies were just one part of the show, which included an array of variety artistes, and every cinema had its orchestra.

Whatever the film conveyed, it would often be accompanied by a sheet from the distributor containing a list of the scenes along with suggested musical compositions

Undoubtedly the best-known cinema orchestra in Dundee in the early days was the 18-piece La Scala, which had the famous Routledge Bell as their conductor.

The Scala orchestra was so famous they would even play concerts in their own right.

There was something magical about the silent movies in those days that transported people into mesmerising worlds of intrigue and romance, adventure and fantasy.

Each cinema had three or four projectionists.

Life in the projection rooms of the early cinemas of Dundee was often fraught with peril because the film stock was made of an extremely flammable plastic.

But, aside from the terrifying possibility of a sudden blaze, life was never dull in the projection rooms, as most of the crews were fond of adding their own ‘special effects’ to the films they were showing.

A favourite trick of the time was to increase the atmosphere by using the lights.

These were not the house lights which came up in the interval but special, more powerful lighting, which was put on to aid the cinema’s cleaning staff.

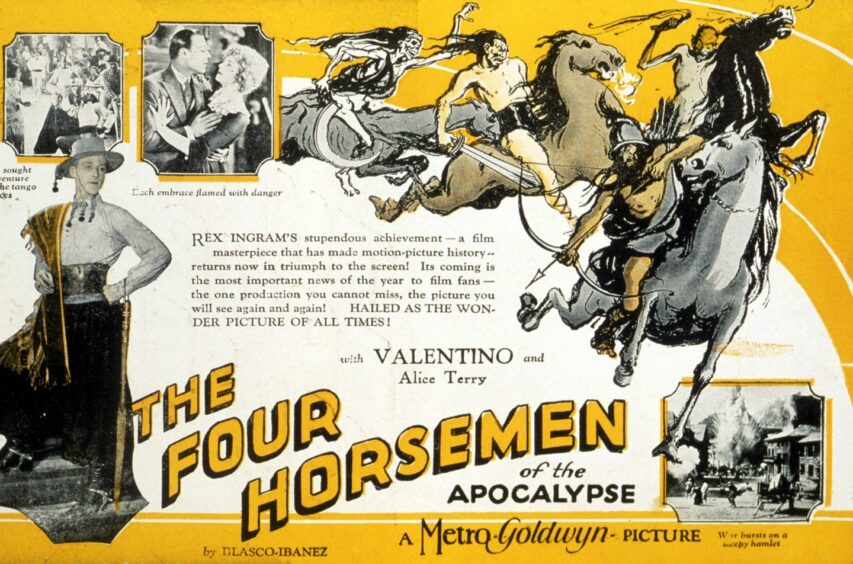

One of the earliest uses of this trick was in Rudolph Valentino’s 1921 breakout hit, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, considered one of the classics of the era.

It was set against the background of war, so projectionists would wait for the dramatic battle scenes before flashing the lights on and off in time with the shell bursts!

It was not unknown for a bulb to burst on cue as staff gleefully watched the scared audience leap from their seats!

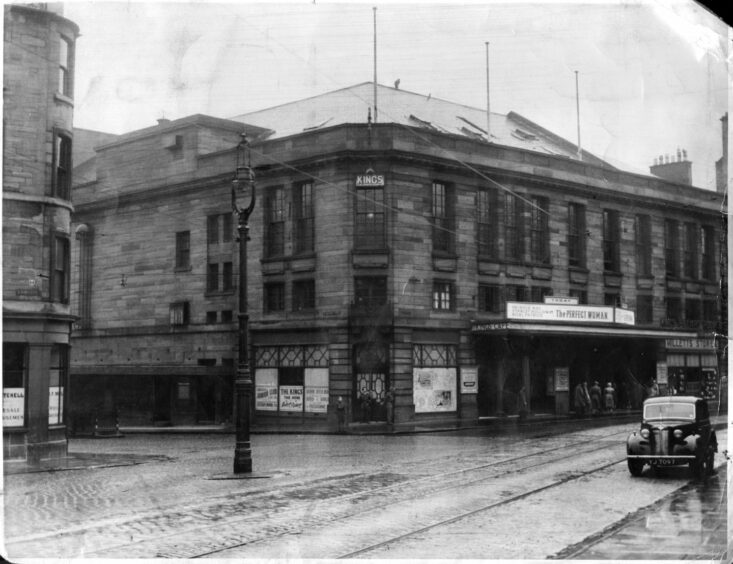

The Kinnaird, too, was always famous for its sound effects, even if it was only men at the back of the hall making the noises of horses’ hooves to confuse the audience as to the direction the steeds were coming from!

The 1920s and 1930s were the great era of the publicity stunt with everyone in the cinema doing something to attract the audiences.

There was no lack of cinema-going public, but competition to attract them was intense.

Week after week the bemused Dundee public would be treated to the sight of gorilla-suited men or Roman soldiers parading the streets handing out bills for the films!

Publicity stunts to promote movies

Taking advertising to the streets was an idea that had been started by one of the great showmen of Dundee, George Caine of the Kinnaird.

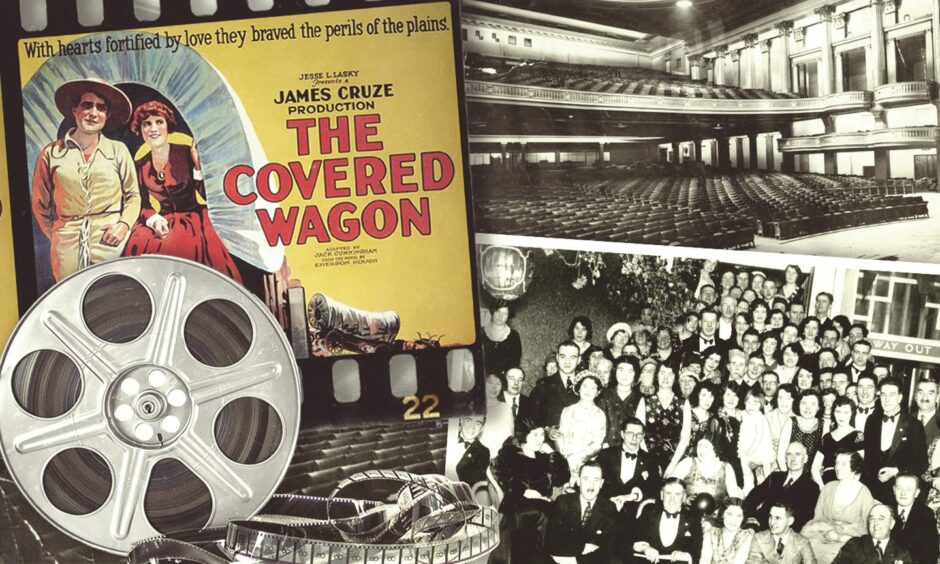

He was the first and really went about it in style with the big-scale pioneer western, The Covered Wagon, from 1923, which was an enormous box-office success.

He kitted out a few people in the cowboy gear and big hats and then drove them round the streets in a mock up of a covered wagon, throwing out bills for the film.

Working in the cinema in those days it helped if you had more than one string to your bow, and projectionists like Billy Illingworth from the Astoria came into that category.

As well as projectionist, Billy was the official poster artist, regularly turning out billboard-sized notices of the coming attractions which were made up of 14 sheets.

A shop near the Astoria lay vacant and was usually used for putting up posters, although Billy and colleague Bill Ramsay used to do their own publicity stunts in the window.

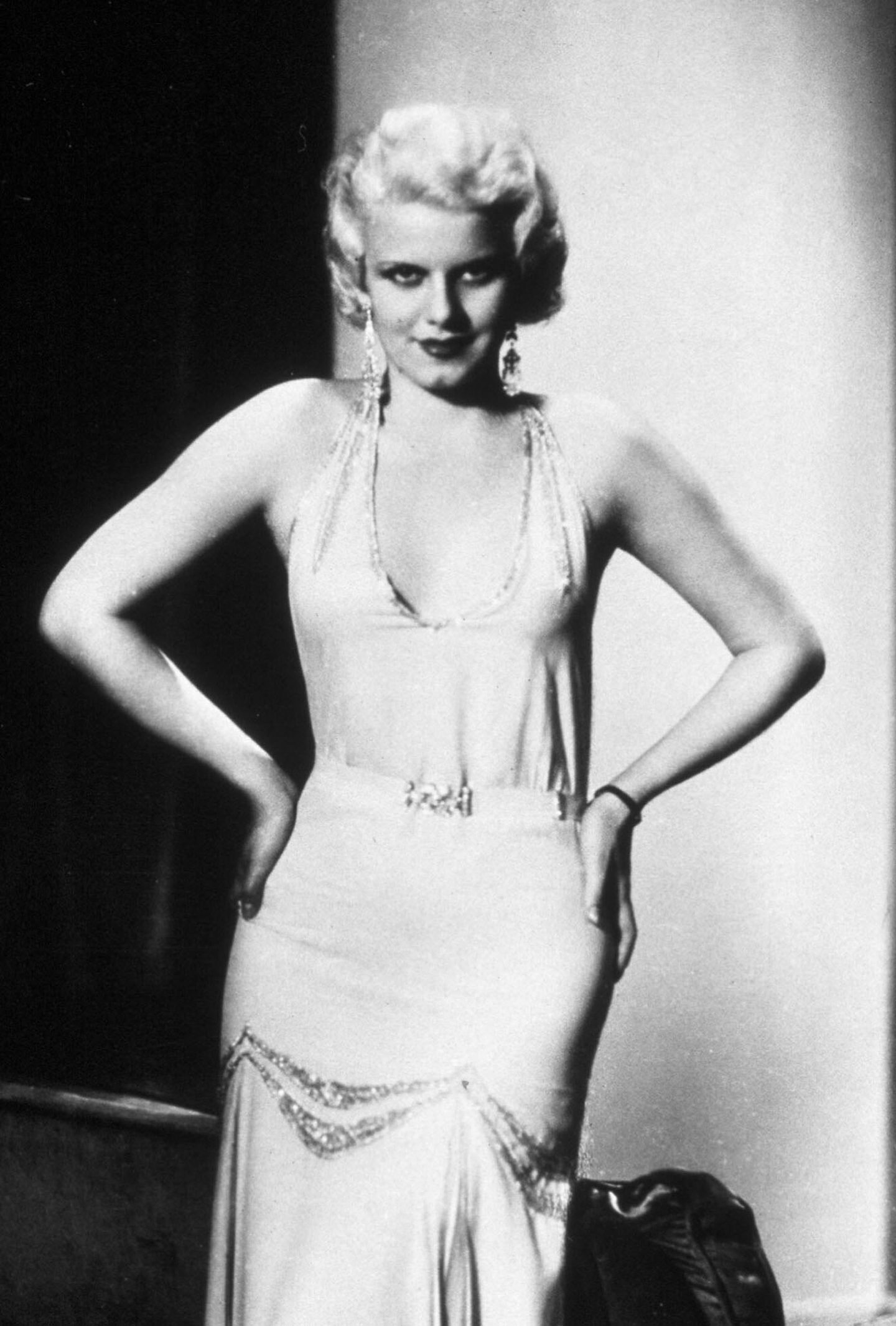

They started with the 1930 war epic Hell’s Angels, which introduced Jean Harlow.

There was one scene where a German Zeppelin made a night raid on London, and they had the shop window rigged up to look like the scene.

Billy made up a little model of the Zeppelin emerging from the clouds as it was picked up with a little spotlight, which attracted a lot of attention to the cinema.

The most successful effort was for a film called Behind The Mask in 1932.

They installed a dummy in the window, complete with mask and dagger in hand.

To add an extra touch of realism, they dipped the dagger in red paint.

No sooner had they put the dummy in the window than they heard terrible screams.

A woman had seen the red paint dripping from the tip of the dagger and thought a murder had actually been committed.

Musicians were put out of work

The arrival of ‘talkies’ like Behind The Mask led the cinema into its greatest period, although it was 1929 before Dundee audiences first heard their heroes speak.

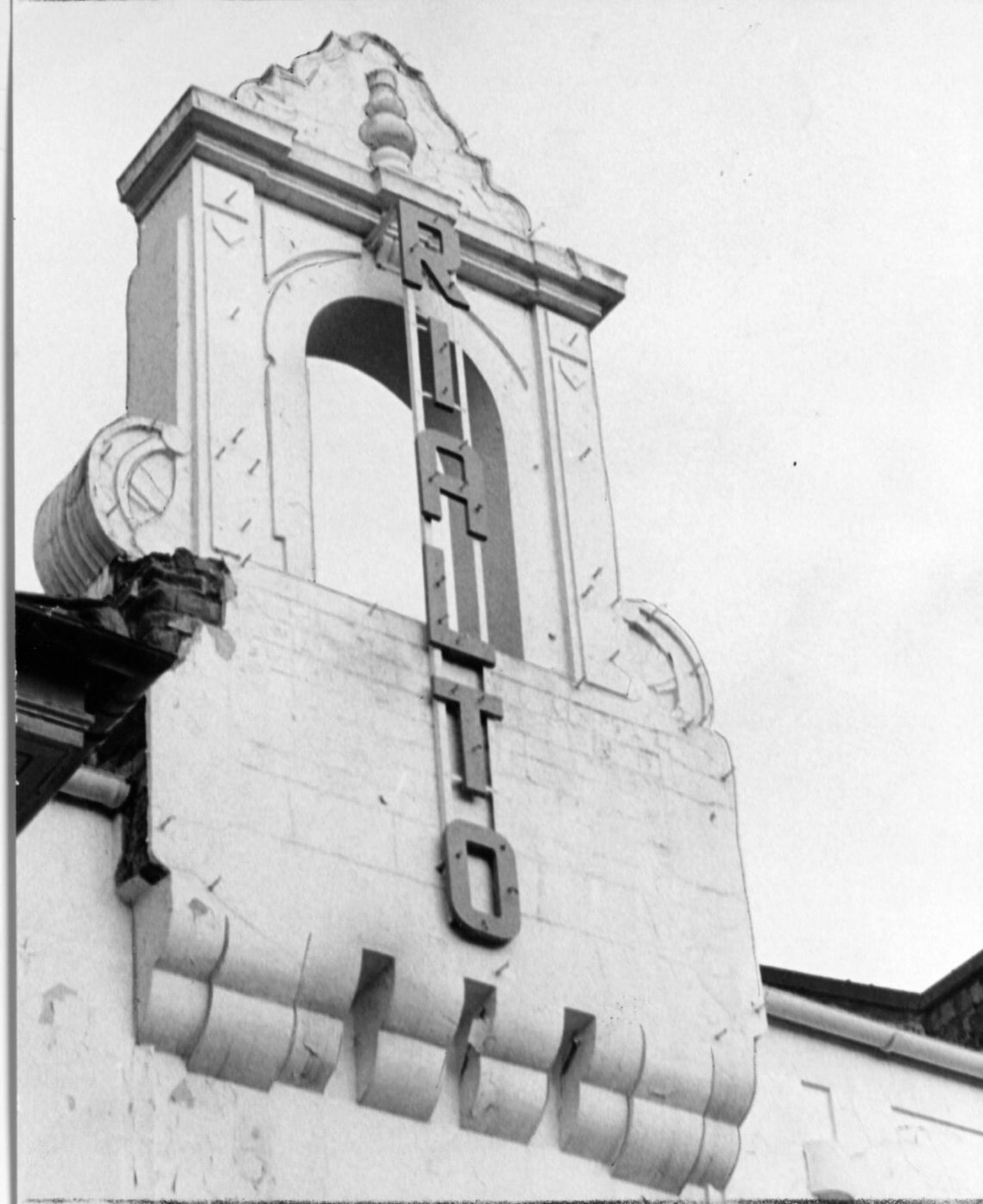

A programme of eight short ‘talkies’ was introduced by John Pennycook in his three cinemas – The Cinerama, The Rialto and The Royalty Kinema – on March 28 1929.

Some months later, in the week beginning July 1 1929, the first feature talking film, Lucky Boy, starring George Jessell, was shown in the same three cinemas.

The price of seat ranged from four-pence to a top-priced seat which cost a shilling.

Some cinema managers thought it was just a fad and were reluctant to pay for the heavy equipment needed for the first talking pictures.

The La Scala was the last to install the equipment, in 1931.

Now the public could hear their stars talk and sing there was no longer a place for the orchestra in the cinemas, with 100 people thrown out of work.

Three musicians used to play in the street every afternoon and would have the hat out at their regular pitch outside D.M. Brown’s department store in the Murraygate.

The hat bore the message: “Out of work due to the talking pictures”.

In those days the sound quality was not exactly uniform, so cinemas showing talkies had a control in the hall that could turn the volume up or down.

The problems the new films caused were usually to be found in the projection box.

Already cramped by the massive projectors, space was made even more limited when the sound equipment was installed, which was provided by a huge record player.

The records themselves were enormous affairs.

They were almost two feet across and played at 33+1⁄3 rpm.

The slightest nudge on the record player would make it jump a groove and you would end up with a man on screen with a woman’s voice and vice versa.

The brief boom stopped in the 1950s

So popular were the movies and the demand to see them, fostered by all the publicity stunts, that people in the 1930s started booking seats.

Several customers used to insist on having their own particular seat and were not afraid to tell anyone in it to move it.

Some nights there were great arguments about this, and the staff would have to be called to sort it out.

At the peak of film-going there were 25 cinemas in Dundee.

Nonetheless, tastes were changing by the late 1950s.

The brief boom was brought to a shuddering halt by the rise of television and the silver screens suffered widespread closures.

Few buildings remain, with many having burned down.

Those still standing are the charming survivors of the golden age of cinema.

Conversation