The site of Scotland’s only Roman legionary fortress was situated on a natural platform overlooking the north bank of the River Tay, south-west of Blairgowrie.

But could the Perthshire town have become the capital of Scotland if the Romans had not suddenly abandoned the site around 86AD?

The tantalising question, first raised in a BBC documentary over a decade ago, continues to fascinate a locally-based retired head teacher.

Researching the history

Wilma Philip, who divides her time between Blairgowrie and Kirriemuir, has been researching the history of Inchtuthil.

The volunteer for Our Heritage, a Blairgowrie group whose aim is to have a heritage centre in the town, recently wrote an article for the group’s website.

However, in an interview with The Courier, she also told how a heritage centre would give local school children a much needed focal point to find out more about the Roman history on their doorstep.

“Like many famous Roman sites, today there is little to see at Inchtuthil,” said Wilma.

“The land is privately owned, and it can appear as just another tranquil area of countryside where cattle graze.

“Yet it was here, on the plateau overlooking the River Tay, that around 83 AD(CE) Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the powerful Roman governor of Britain, built the vast legionary fortress.

“Many forts, fortlets, camps and watchtowers were built by the Romans in Scotland.

“But Inchtuthil is Scotland’s only legionary fortress.”

Lynchpin of invasion

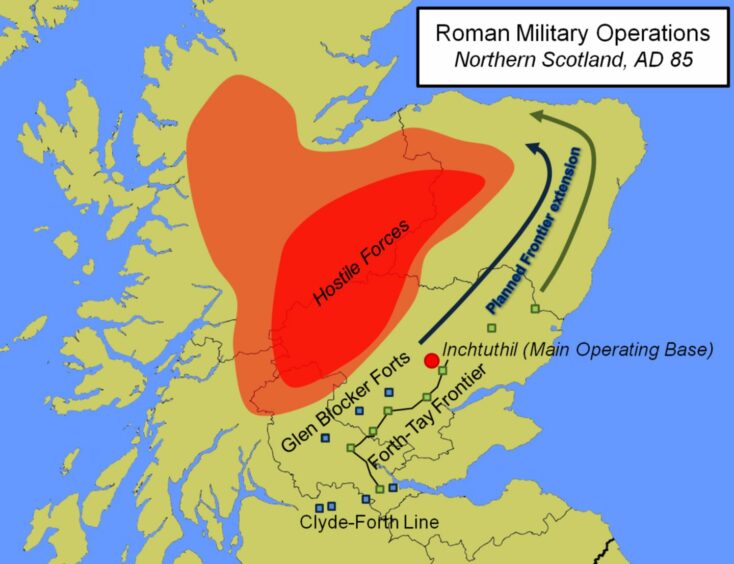

Wilma explained that Inchtuthil is regarded as the lynchpin of Agricola’s campaign to subdue the Iron Age tribes, the Caledonians, and to take control of Caledonia (Scotland).

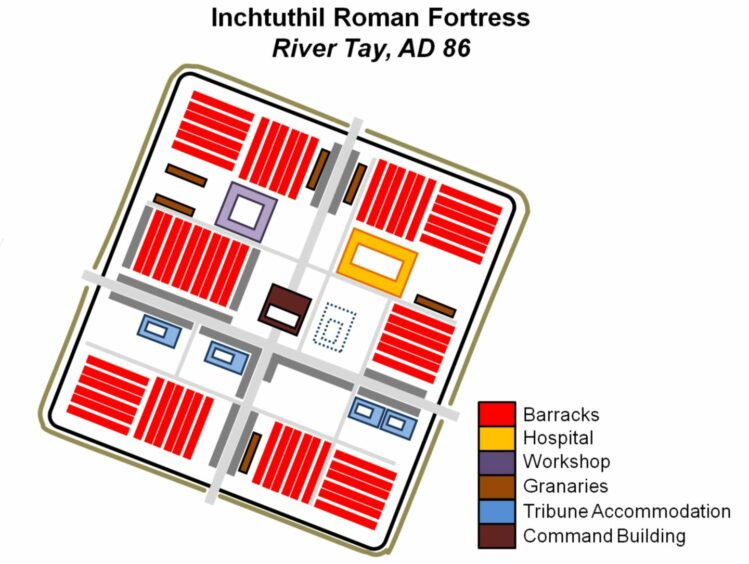

The fortress covered approximately 53 acres (21.5 hectares) which is the size of 25 football pitches.

It was larger than the fortress at York and accommodated around 5500 soldiers of the Legion XX Valeria Victrix, in 64 barrack blocks.

Wilma explained that most of the buildings would have been enclosed and protected by ditches, palisades, ramparts and watchtowers.

Two main streets ran through Inchtuthil and into the countryside beyond: the Via Principalis and the Via Praetorian.

Each of the four gateways into the fortress would have been vast wooden structures guarded 24/7.

At the centre of Inchtuthil was the administrative building or headquarters: the Principia, she said.

Excavations revealed that it had a 160-foot frontage and a large courtyard as well as the administrative offices.

Yet the Principia at Inchtuthil did not fill the space allocated for it.

She states that it may be that it would have been replaced by a much larger, grander building had the Legion XX remained.

Why was Inchtuthil abandoned?

Wilma explained that although plans for Inchtuthil included a large area for the commanding officer’s house (praetorium), it had not been built before Inchtuthil was evacuated and abandoned around the summer of 86 AD(CE) or early in 87 AD(CE).

It’s been suggested the reason for the abandonment was probably that Legio II Adiutrix had been called to Moesia from its base in Deva Victrix (Chester) to deal with a Dacian invasion in 86 AD.

Valeria Victrix, at Inchtuthil, was obliged to move back south to take its place.

Archaeology has suggested the site might have been in use longer than previously thought.

Discovery of hand-forged nails

Excavated from 1952, there was a startling discovery in 1960 when nearly one million hand-forged nails were found buried beneath what would have been a workshop.

That they were concealed deliberately and thoroughly by the retreating Romans is explained by the Roman chronicler Tacitus who wrote that the Caledonian tribes valued iron more than silver or gold, as it could be hammered out into weapons.

The nails were new, and were of all sizes up to 16 inches in length, with a total weight of 12 tons.

Following their discovery, the National Museum of Antiquities was given a selection of the nails, and sets were freely gifted to major museums around the world.

In the summer of 1962, around 800,000 nails were offered for sale to collectors at five shillings (25p) each or £1.5s for a selection with a commemorative label.

Others were recycled at the Motherwell steel works.

It is also thought some were used by atomic scientists to estimate the corrosion effects on barrels of nuclear waste.

How did Wilma get interested?

Wilma’s interest in history dates back years.

Originally from Aberdeenshire, she spent her primary school teaching career in Midlothian, with the last 14 years as a head teacher.

Retired now for around 20 years, it had always been her intention to retire to Perthshire as it’s one of her favourite places.

She regards Blairgowrie as an “absolutely lovely town” and enjoys the history and trying to “sell it a bit more”.

Yet when she started reading more about the history of the area, she discovered that, other than a few passing references and a couple of mentions in Perth, Edinburgh and Glasgow museums, there was nothing of substance about the history of Inchtuthil.

Then, in 2012, in the BBC documentary ‘Scotland: Rome’s Final Frontier‘, Dr Fraser Hunter, principal curator of Iron Age and Roman collections at the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh, pointed out that great cities like York and Chester developed from Roman fortresses.

He suggested that, had the Legion XX remained at Inchtuthil, there was the potential for it to have become the location of Scotland’s capital city.

Wilma said this revelation sent “shivers” down her spine.

She contacted Dr Fraser, and Professor Matthew Nicholls of the University of Reading.

Both were “very generous” with information and Professor Nicholls in particular gave permission for her to use digital reconstructions of Inchtuthil in her timeline.

She was also fascinated by the history of the Roman bath house at Inchtuthil.

Not only was the expertise needed to build it “really intriguing”, but the people involved in the building of it seemed to have been involved in constructing a similar bath house in Bearsden and in Bath itself.

The Cleaven Dyke

Another mysterious structure of local interest in the area which she’s written about is the Cleaven Dyke.

Cutting across the A93 between Meikleour and Blairgowrie, she describes it as the finest prehistoric monument of its type in Britain.

It is a vast earthwork measuring some 2.6km long, averaging 9m wide and 1.8m high in place.

Cleaven Dyke was thought to be a Roman defensive structure, possibly linked to the Roman forts at Inchtuthil and Meikleour, she said.

However, excavations carried out in 1993 suggested it to be a Neolithic Cursus.

The purpose of a cursus is open to debate, but it may have been a ritual monument or perhaps a processional route.

Whatever its purpose, Wilma is amazed how few local people are aware of it.

Heritage centre ambitions

Having established Our Heritage in November 2018 with the aim of getting a heritage centre in Blairgowrie, she says it further cements the need for a local focal point, not just of local history, but history of national and European significance.

“Blairgowrie is the largest town in Perthshire and has never had anything like this to display and promote its history, mainly, if I may say so, because Perth keeps the money,” she said, adding that the Covid-19 pandemic inspired Our Heritage’s ongoing online presence.

“Here in Blairgowrie, there’s nothing so far that’s suitable for what we really want. I’m sure we could get somewhere if we wanted a little folksy museum.

“But we want something to be more educational, entertaining, immersive – all of those things.

“It’s difficult to get a building that would accommodate that. There are lots of buildings but they just wouldn’t be fit for purpose really.

“We are still searching. And of course funding is an issue!”

In her primary school teaching days, history was part of the curriculum, as it is today.

But she believes more can be done to promote local history and heritage.

“The Scottish curriculum dictates that children should study an era of history,” she said.

“Roman history is one of the eras that’s quite popular in primary school.

“It’s so easy to involve the children in making things connected with the Romans and learning Roman numerals and dressing up as a Roman soldier – this sort of thing.

“I think it’s very important for young people to learn of that period in history.

“But I would like to see somewhere in Blairgowrie where school children could come and learn more about their Roman history.

“There is currently nowhere they can go to learn about Inchtuthil, which is really sad because in the first century, it was a major site. It housed at least 5000 soldiers. It was huge.”

- To find out more about Our Heritage Blairgowrie, go to ourheritageblairrattray.scot/

Conversation