Ahead of a special RSGS talk in Perth, Michael Alexander speaks exclusively to the leader of the expedition that found Shackleton’s lost ship Endurance beneath the Antarctic.

It was a remarkable discovery that captured the imagination of the world.

Almost 107 years after Sir Ernest Shackleton’s historic ship Endurance was crushed by pack ice and sank during an expedition, the lost wreck was found in the Antarctic.

Where was the wreck found?

On March 5, 2022, a team of adventurers, marine archaeologists and technicians located the wreck 3008 metres down at the bottom of the Weddell Sea, east of the Antarctic Peninsula, using undersea drones.

Battling sea ice and freezing temperatures, the team had been searching for more than two weeks in a 150-square-mile area around where the ship went down in 1915.

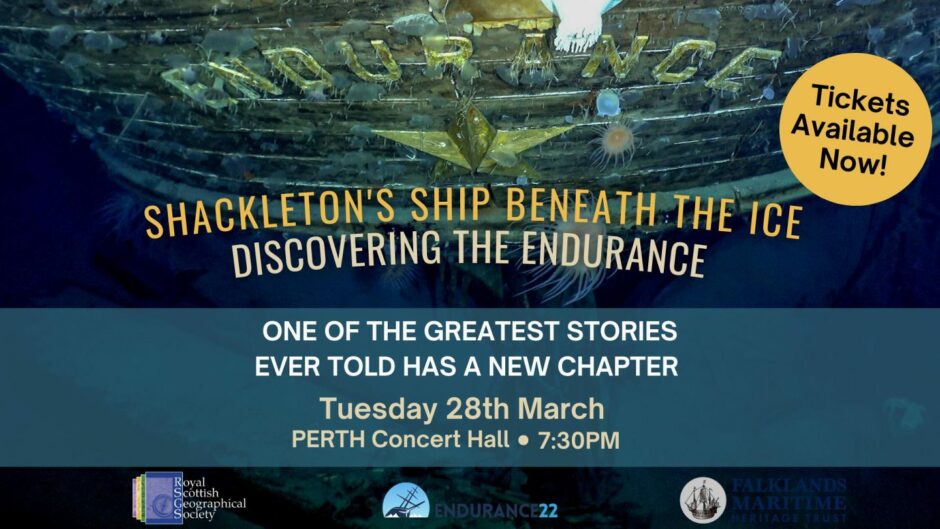

But as the team prepare to speak at a special Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS) event in Perth on March 28, the Endurance22 expedition leader has revealed that when the amazing discovery was made, they were just days away from calling the search off.

“We’d been searching for a long period,” said Dr John Shears in an exclusive interview with The Courier.

“On February 16 last year we got onto the wreck site.

“We’d been working 24 hours a day using these autonomous underwater vehicles.

“We had a very specialised subsea team with us led by brilliant French engineer Nico Vincent, searching the seabed.

“But on the day that we find the wreck I’m actually off the ship.

“Because we were so late in the season – the sea ice was beginning to freeze all around us, the weather was deteriorating, we’re getting much colder temperatures down to minus 18C – I know we can’t stay on the wreck site for very much longer.

“We’re on day 18 of the search and I know that on day 20 I’m going to have to call it all off.

“I go off the ship with our director of exploration Menson Bound to have a chat and think through how we are going to manage the search in these final few days.

“We actually go off to a look at an iceberg that’s locked into the pack ice, to take a few photos.

“But as we came back, I can still remember very vividly turning round and saying ‘today is going to be a really good day – I can just feel it’.

“I even said ‘I think she’s beneath our feet’!”

From fear to elation

Walking on the metre-deep sea ice, John and his colleague had switched their radios to a safety channel.

This meant they were oblivious to any radio chatter on board the ship, a South African icebreaker, Agulhas II.

Arriving back on board, John feared the worst when a tannoy announcement immediately ordered them to the bridge.

Having lost a multi-million dollar autonomous underwater vehicle, which forced the abandonment of their first search in 2019, had their latest drone also disappeared?

Or worse, had there been a bad accident?

Arriving on the bridge, his fears were compounded when he saw their project manager Nico looking glum, alongside documentary film director Natalie Hewit.

Then, changing the mood immediately, Nico held up his iPhone and said: “Gentlemen, I’d like to introduce you to the Endurance!”

Nico showed them a beautifully crisp, high-resolution sonar image of the wreck some 3km below.

It clearly showed the mast, the funnel – and John recalls how everything “just went bonkers”!

“People are jumping up and down, hugging, shaking hands, slapping each other on the back,” he said.

“It was an incredible moment. I was absolutely dumbstruck for several minutes.

“I’d spent five years of my life full time on this project.

“I’d given up lots of other opportunities and possible work.

“To have finally found the wreck against all the odds when many experts had said this was the impossible search, there was huge pride in the team and enormous satisfaction.

“It was a brilliant moment. The pinnacle of my polar career!”

Remarkable preservation of wreck

When news of the discovery was made public, and with thousands of social media users already following the team’s every move, many experts commented that they’d never seen a wooden ship wreck like this in such pristine condition.

John said that when compared with the famous photographs taken by Shackleton’s cameraman Frank Hurley as she was being crushed by the ice in 1915, she looked “just like she did as if she sank yesterday”.

The remarkable state of preservation was down to a number of factors.

At that depth, Antarctic bottom water temperature is minus 1.5C, no light penetrates, there are few ocean currents and, because it’s so cold, there are no ship worms to consume the wreck.

There’s also no sediment because the super clear waters of the Weddell Sea are fringed by ice shelves.

What was also crucial to the success of the operation, however, was the accuracy of the sinking co-ordinates left by Shackleton’s captain, Frank Worsley, in his diary and logbooks.

In the end, the wreck was found just 7km or four nautical miles from Worsley’s original sinking position.

“That’s quite incredible really given that in 1915 there was no GPS,” said John.

“All navigation was carried out manually using a sextent while camping on the shifting ice and having just lost their ship.”

For most shipwreck hunts, when ships have been sunk in an emergency or as an act of war, there tends not to be an exact location recorded.

But when John’s team took on the challenge of finding the Endurance, they had the advantage of being able to go into the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge and look at their archive material, including the diaries and logbooks.

Greatest survival story ever?

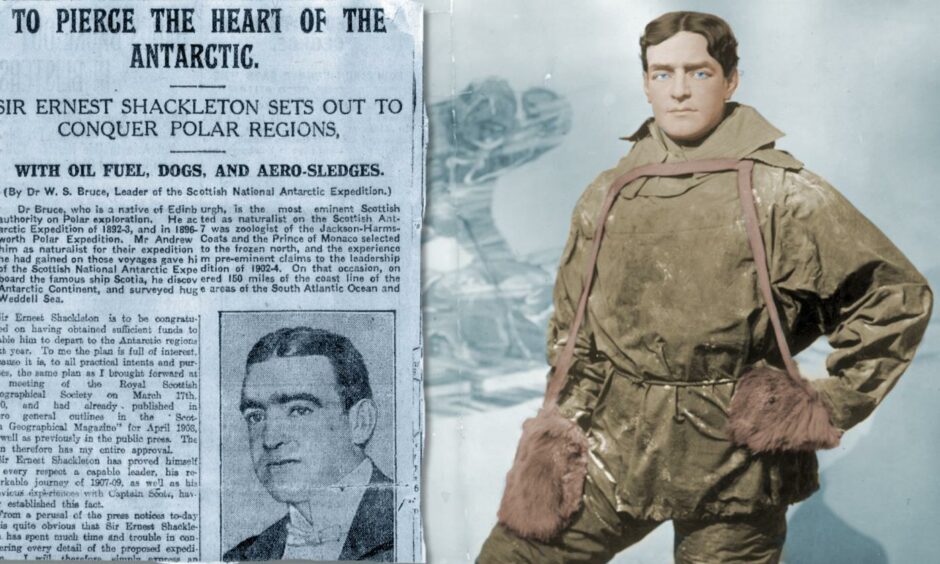

Embarking upon the Imperial Trans-Atlantic Expedition, it was Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ambition to achieve the first land crossing of Antarctica from the Weddell Sea via the South Pole to the Ross Sea.

In the Weddell Sea, Endurance never reached land and became trapped in the dense pack ice.

The 28 men on board eventually had no choice but to abandon ship.

After months spent in makeshift camps on the ice floes drifting northwards, the party took to the lifeboats to reach the inhospitable, uninhabited, Elephant Island.

Shackleton and five others then made an extraordinary 800-mile (1,300 km) open-boat journey in the lifeboat, James Caird, named after the wealthy Dundee jute baron, to reach South Georgia.

Shackleton and two others then crossed the mountainous island to the whaling station at Stromness.

From there, Shackleton was eventually able to mount a rescue of the men waiting on Elephant Island.

It was Worsley’s expertise as a navigator and sailor alongside the expertise of Shackleton and other key crew members that helped save the lives of all 28 men against all the odds.

“Captain Frank Worsley was probably the world’s best navigator in the early 1900s,” said John.

“He was expert at using a sextent, but also used theodolite to take star sightings as well.

“Worsley always knew exactly where the ship was and when they lost the ship and were camping on the ice, he also used navigation then.

“They were on the ice for months as it drifted north and melted.

“His expertise was also crucial to the success of the remarkable rescue mission abroad the James Caird.”

Dr John Shears: Polar career

Growing up in Exeter, and going on to become a geographer before 25 years working at the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge, John was always fascinated by this amazing story of survival.

During his career, he’s visited Shackleton’s grave on South Georgia several times and also surveyed Shackleton’s huts while seconded to a New Zealand team in 2005.

He’d not long set up his own exploration company Shears Polar Ltd when Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust chairman, Donald Lamont, asked if he’d be interested in leading the expedition to search for Endurance.

But just as teamwork helped Shackleton overcame what seemed impossible in 1915, the discovery of the wreck in 2022 also overcame the doubters, which is something that John and his own team are immensely proud of.

Given that Sir Ernest Shackleton was secretary of the then Edinburgh-based RSGS from 1904-05, John is very much looking forward to giving the team’s first Scottish expedition talk where the society is now based in Perth.

In the Perth Concert Hall event talk hosted by the RSGS, a first-hand account will be given by members of the team.

They’ll recount their amazing discovery and their journey beneath the ice to photograph and film the legendary ship.

Power of communication

Just as Shackleton understood the power of photography and media in the early 1900s, the Endurance wreck team want to communicate their story – and that of Shackleton’s – to a whole new generation.

“I’m delighted to be speaking to the RSGS,” said John, who is now helping to work on a conservation plan for the Endurance wreck.

“I’m looking forward to seeing records and finding out more about what Shackleton did when he was secretary.”

Last week, National Geographic Documentary Films announced that Academy Award-winning directors Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin along with BAFTA-nominated director Natalie Hewit are set to direct ENDURANCE (working title), a documentary film based on the epic search to find the lost ship of Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton.

The announcement comes on the heels of the one-year anniversary of the ship’s discovery.

Ticket information

*Shackleton’s Ship Beneath the Ice: A Spirit of Endurance, Tuesday March 28, Perth Concert Hall, 7.30pm, tickets: www.perththeatreandconcerthall.com

Conversation