The voices in the dark were the only guide to the trapped men when the roof of a Fife pit collapsed on May 10 1973.

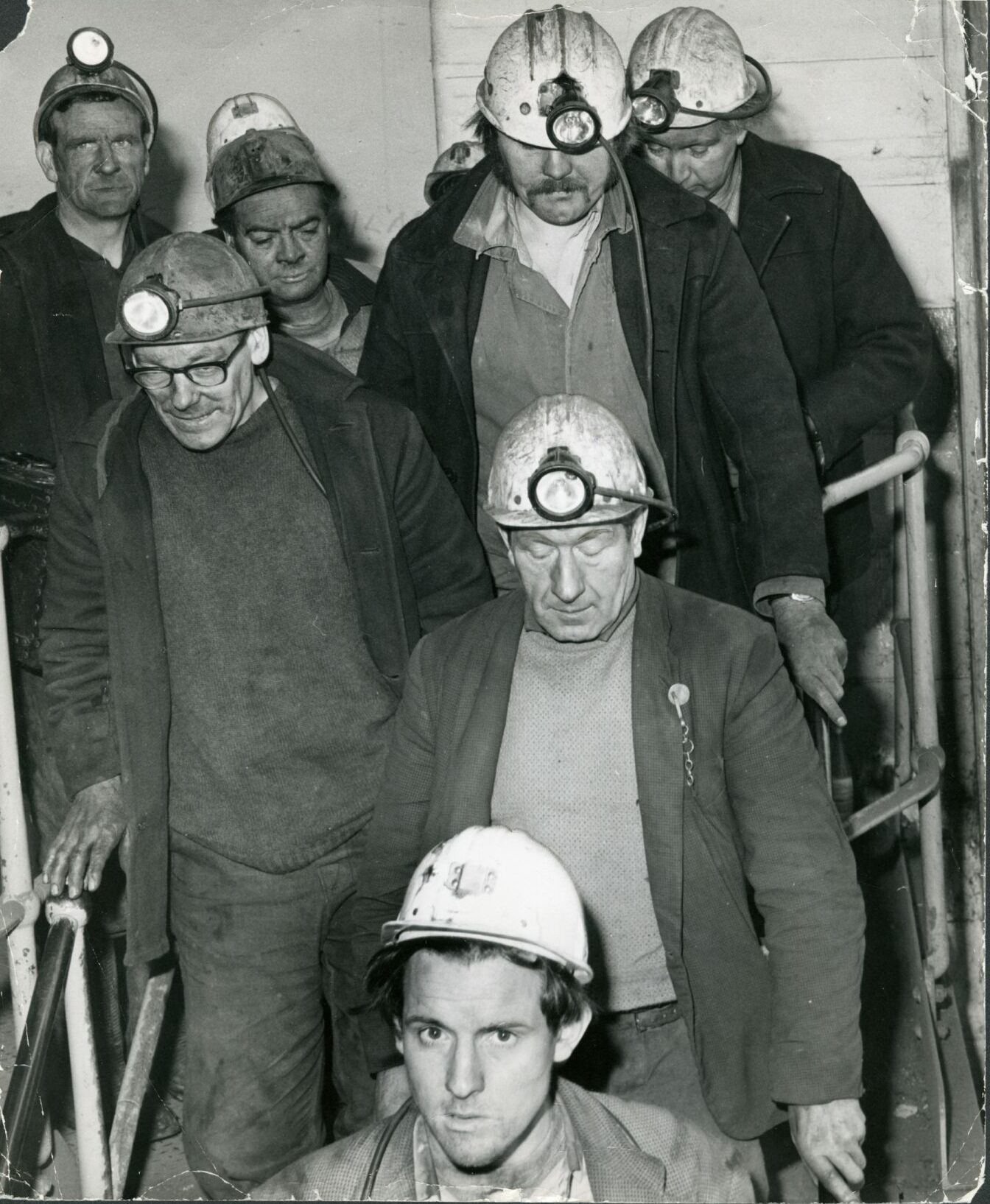

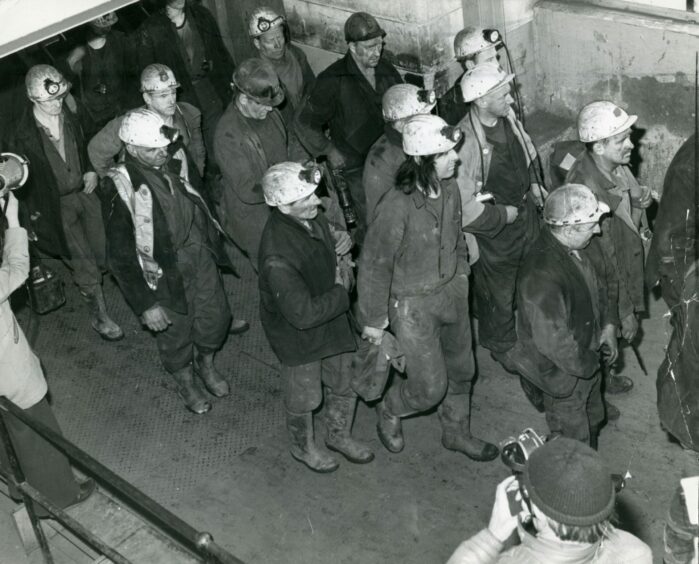

Miners clawed at the debris with bare hands in a frantic effort to free their colleagues when the steel pit props succumbed to the raw power of nature.

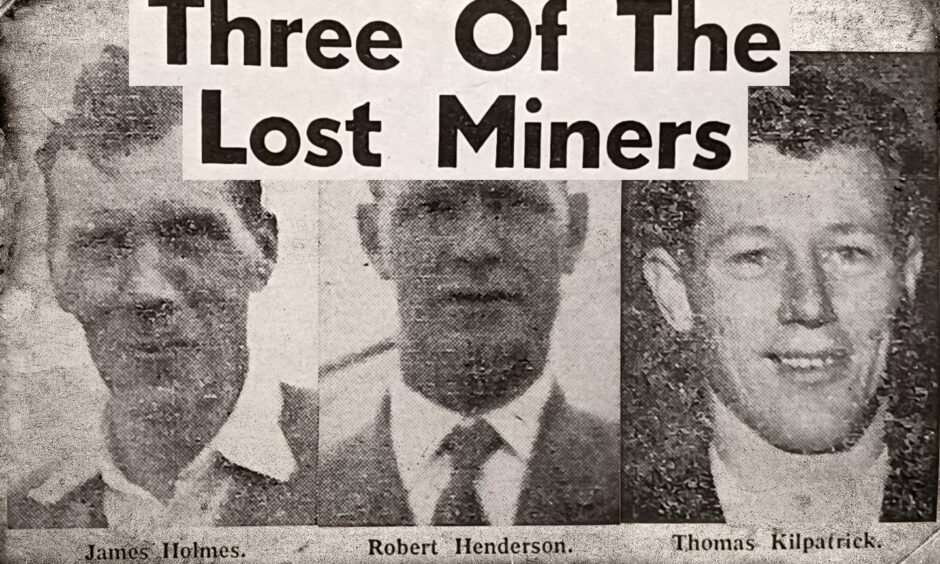

But it was not enough to save James Comrie, Angus Guthrie, Robert Henderson, James Holmes and Thomas Kilpatrick.

Mr Guthrie — the youngest of the dead men — was about to turn 21 later that month, while Mr Kilpatrick’s wife had urged him not to work that day because he was hurt.

The tragedy stunned the close-knit community.

Rescue teams toiled all night

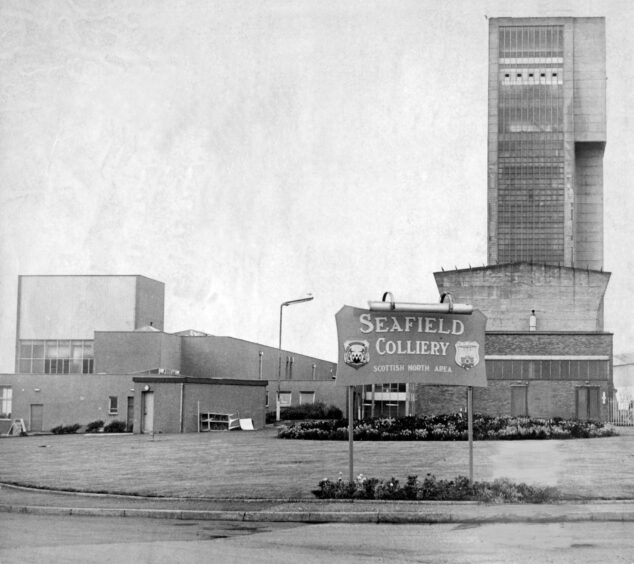

The men had been working on a new seam at Kirkcaldy’s Seafield Colliery — stretched out under the Firth of Forth — when a large section of the roof gave way at 6.45pm.

The darkness was all-enveloping.

John McCartney from Kirkcaldy escaped immediately and gave the approximate location of the trapped men and confirmed that they were still alive.

Mr McCartney had four fractured vertebrae in his back and a collapsed lung.

A rescue mission was launched in an attempt to save them.

Robert Henderson was brought to the surface at 12.30am and placed on a stretcher.

The 59-year-old from Buckhaven died almost immediately.

He had worked in the pits all his life and the last time his wife, Henrietta, saw him alive was when he went to catch the colliery bus at 1pm that Thursday.

Mr Henderson had one son and three daughters.

James Holmes, 53, from Methil, James Todd, 29, from Kirkcaldy, David Dickson, 48, from Buckhaven, and Edward Downs, 57, from Leven, were released around 1.30am.

Mr Todd suffered a head injury and a broken jaw.

Mr Holmes died soon after being brought to the surface.

He had worked in the pits for 21 years and left Wellesley for Seafield in 1967.

Mr Holmes and his wife, Mary, had three sons.

Mr Dickson and Mr Downs prayed and tried to keep cheerful with their other trapped workmates while rescuers worked towards them.

“We were on the way back up from the coalface when the roof literally opened and we were buried all over,” Mr Downs told The Courier afterwards.

“I knew it was a bad fall because other men near me were moaning and groaning.

“I couldn’t do a thing to help them as only my head protruded from the rubble and I could not move my body, at all.

“As we lay there we could hear the occasional small falls from the roof, and all the time we were terrified there would be another major disaster.”

“But that didn’t stop the men rescuing us from superhuman efforts to get us free.

“No tribute is high enough to their bravery.”

Mr Downs was, in fact, no stranger to tragedy in Fife’s pits.

He was among 2,000 people put out of a job when a fire at the Michael Colliery in East Wemyss in September 1968 claimed the lives of nine men and closed the mine for good.

Three men were assumed dead

At about 4.30am a National Coal Board spokesman said there was hardly a glimmer of hope for the remaining three men — James Comrie, Angus Guthrie and Thomas Kilpatrick.

“Every effort has been made to reach the last three men, but it must now be assumed that these men are dead,” he said.

“Recovery work will go on, but in view of the difficulties and dangers involved it will have to be done with due regard to the safety of the recovery teams.”

James Comrie’s body was recovered at midday on May 11 1973.

Mr Comrie, 49, from Buckhaven left behind a wife and two sons aged 19 and 26.

After the disaster, the pit reopened.

The retrieval of bodies continued.

Mr Guthrie’s body was taken to the surface on May 19, although no trace could be found of Mr Kilpatrick, whose body was not recovered from the pit until 3.30pm on June 6.

Mr Guthrie, of Cardenden, would have celebrated his 21st birthday on May 26.

The family had already begun buying his gifts.

When he left school he worked for a short time in a factory and later went to the National Coal Board training centre before entering the pits as a teenager in 1970.

One of his interests was first-aid.

At 8am on the morning after the tragedy he should have been on a bus taking a party of miners from Seafield to compete in the NCB first-aid competition at Harrogate.

A sliding doors moment in Seafield colliery tragedy…

Mr Kilpatrick, 38, of Methil, meanwhile, might never have gone down the pit.

It emerged that he bruised his ribs and head after falling from a roof just three days before the tragedy at Seafield.

His wife, Christina, pleaded with him to stay off work.

He refused.

It was a sliding doors moment but with a far sadder ending.

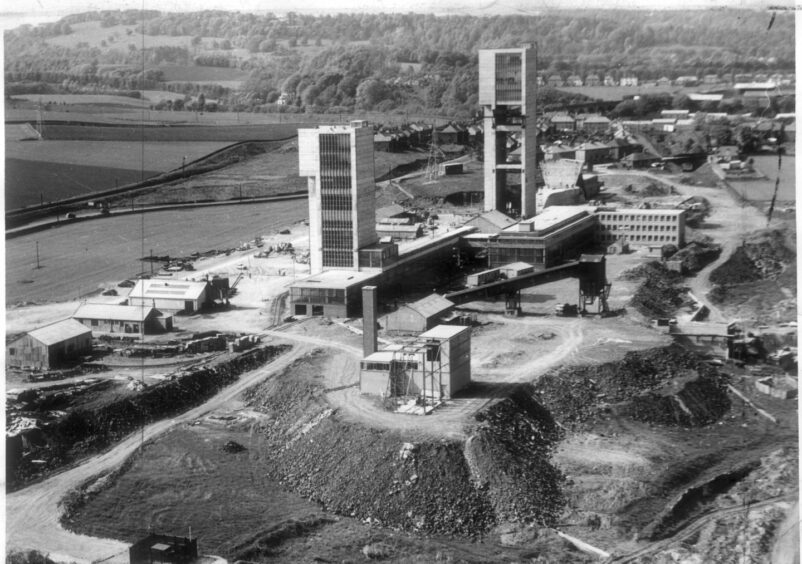

Seafield Colliery was one of Scotland’s successful superpits after production began in 1965 and the weekly output was an average of 26,000 tons at the time of the tragedy.

The tragedy once again highlighted the cost of Scotland’s coal.

Kirkcaldy provost John Kay, himself a former miner, was “shocked and disturbed”.

“It is one of the things that we in mining areas have to live with,” he said.

“And, while it is seven years since the disaster in the Michael, this tragedy is even more reinforced by the fact that some of the men involved actually come from that area.”

At the time of the accident the weekly output was an average of 26,000 tons with 2,100 men employed below ground and 300 on the surface.

The survivors spent weeks in hospital recovering from their injuries.

A public inquiry at Kirkcaldy in August 1973 concluded that the supports were not stable enough to have been placed on the steep incline on which they were used.

King Coal’s glorious reign ended

At its peak the Scottish coal mining industry employed 150,000 in 500 pits; by 1914 in Fife alone 30,000 men worked in the mines, an astonishing one tenth of the region’s population.

By the late ’50s, it still gave work to 85,000 miners in more than 150 Scottish pits but it stuttered in the ’60s and ’70s and the once-proud industry was reduced to a rump by the time of the bitter 1984 miners’ strike.

Seafield Colliery closed four years later.

The final nail in the coffin of the once-thriving pit came when what turned out to be impossibly tough production targets were set.

Its twin towers were demolished in 1989 and today there is little to remind locals and visitors of the industry which was once Kirkcaldy’s biggest employer.

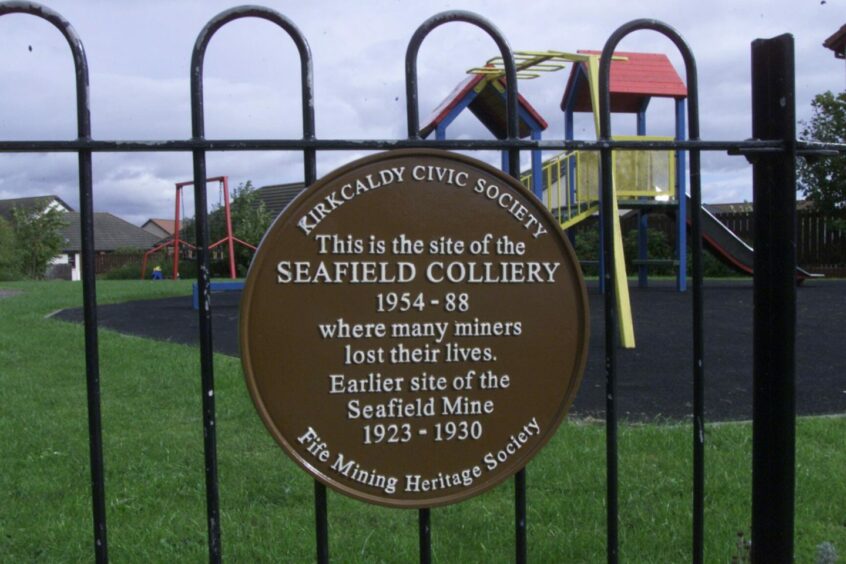

The Seafield site is now a sprawling residential area.

All that remains of the pit is a small plaque on the side of a playpark that was unveiled by Kirkcaldy Civic Society and Fife Mining Heritage Society in 2004.

Those who died will never be forgotten.

The 50th anniversary of the tragedy will be marked by a wreath-laying ceremony and two-minute silence at Seafield beach at 6.45pm, organised by the 80th Linktown Scouts.