It’s now 80 years since Wing Commander Guy Gibson led the Royal Air Force’s 617 Squadron on a dangerous mission to cripple the Third Reich’s industrial centre.

On the night of May 16-17 they flew their Lancaster bombers to the heart of Germany and dropped Barnes Wallis’s revolutionary “bouncing bombs” to breach the dams that supplied the Ruhr Valley’s factories with water and electricity.

Yet by the end of the mission, codenamed Operation Chastise, 53 of the 133 men who participated in the attack were killed, which prompted Wallis to question whether such losses could ever be justified.

Two of the most experienced crews, led by Flt Lt Bill Astell and Flt Lt Robert Barlow, were lost on the flight into Germany, after crashing into electricity cables which were difficult to see in the moonlight.

The immediate explosion of the mine on board offered no hope of survival.

He joined the RAF in 1939

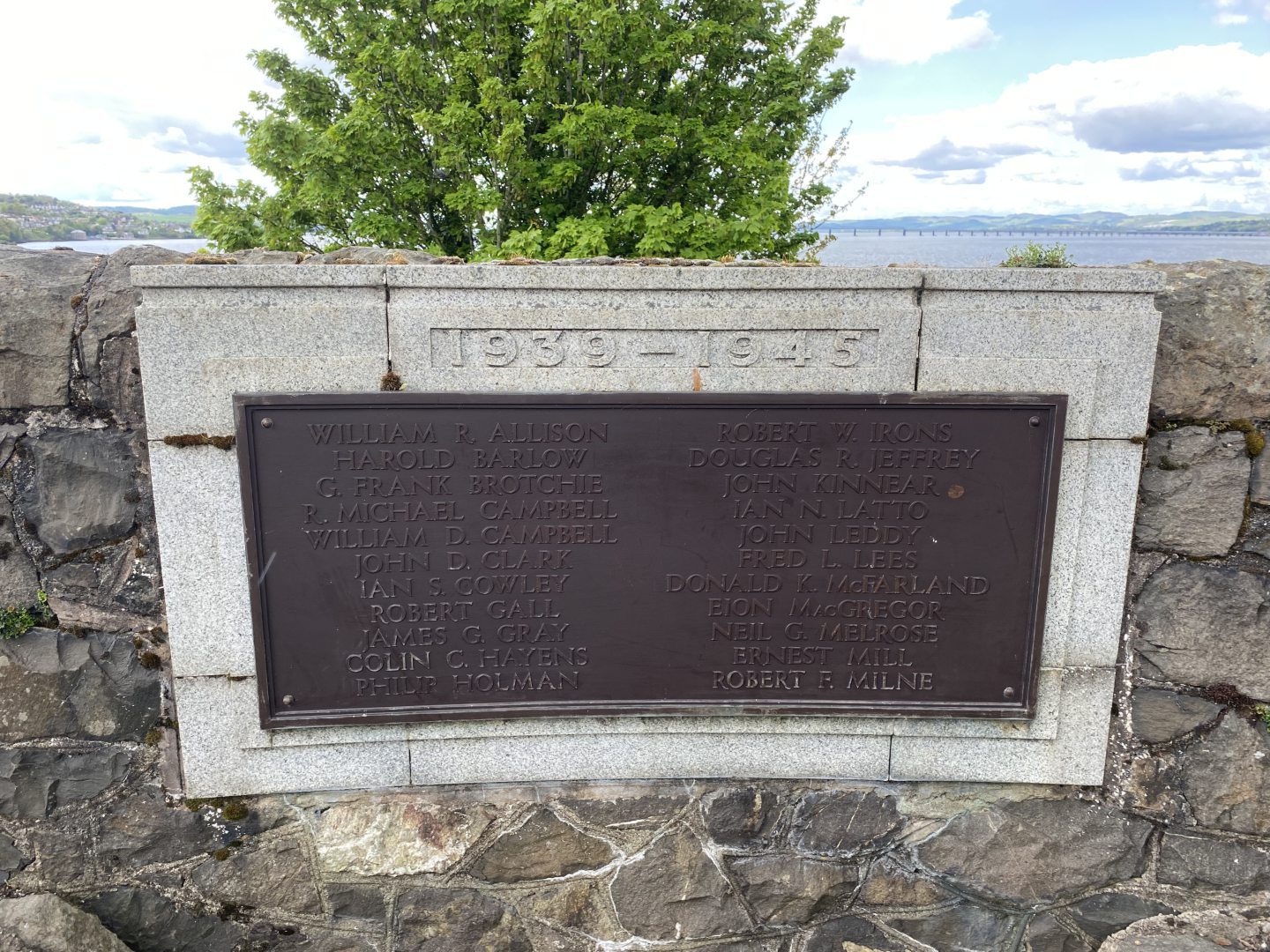

Astell’s Flight Engineer was 21-year old John Kinnear from Newport-on-Tay whose father had been a chauffeur for local MP and publisher Sir John Leng and his family.

Kinnear was born on November 6 1921 in the block called Poplar Place, which is now 21-25 King Street in Newport, before moving to 107 Tay Street in 1930 aged nine.

He was a mechanically-minded young man who worked with Don’s Garage in King Street before joining the RAF aged 16 in 1939 a few months before war broke out.

Dr Iain Murray, a local expert and writer on The Dam Busters, from the University of Dundee, said the entire flight would have been done at just under 100 feet in the dark.

He said: “Sgt Kinnear, who was known as Jack in the family – and inevitably as Jock in the RAF – joined up on the outbreak of war and mustered as groundcrew.

“When four-engined bombers were introduced in 1942, the RAF created the new aircrew role of Flight Engineer to monitor the complex systems in the aircraft – many were recruited from groundcrew, and Kinnear was one of those to volunteer.

“After training in Cornwall, he joined Astell’s crew in 57 Squadron at RAF Scampton and they flew eight missions before their whole crew was transferred to the new 617 Squadron to train for the dams operation.”

How did the bouncing bomb work?

The Ruhr, and particularly its dams, had actually been identified by the British Air Ministry as important strategic targets even before the outbreak of the war.

As well as supplying power to the region and pure water for the Ruhr’s steel mills, the dams also supplied drinking water and water for the canal transport system that allowed Germany to move vital war material from the factories to the front lines.

Dr Murray said: “Experiments showed that a four-ton bomb could break a dam – but only if it was in contact with the wall, and it was to solve this problem that led Wallis to the ‘bouncing bomb’ idea.

“Released at a specific height and speed, the bomb would skip over the water and come to rest against the dam wall before exploding.

“The piloting skills required to drop the bombs, codenamed Upkeep, led to a special squadron being formed, and this was led by Wing Commander Guy Gibson, who had just completed his third tour with Bomber Command.

“The story of the development of the weapon and the formation of the squadron is well told in the 1955 movie The Dam Busters despite Upkeep still being secret at the time, and the movie remains a perennial favourite on TV.”

The targets selected were the Mohne and Sorpe dams, with the Eder dam being a secondary target.

Intensive training began with the problem of releasing the bombs at the correct height solved by mounting a spotlight in the nose and tail of the Lancasters – when they converged on the water’s surface the bomber was flying at the optimum 60 feet.

Dr Murray said: “On the evening of May 16 1943, 19 Lancaster bombers, which had been modified to carry the ‘bouncing bombs’, took off from RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire to head for Nazi Germany.

“Flying at tree-top height to avoid enemy fighters and anti-aircraft fire, only 12 of the aircraft managed to reach the target area, and a further three were lost during the attacks or on the flight home.

“Fifty-three of the aircrew were killed, and a further three baled out and became prisoners of war.”

So what happened to Sgt John Kinnear during Dambusters raid?

“On the outward flight, it is likely that Astell’s aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire and then hit an electricity pylon, causing the aircraft to crash to the ground,” he said.

“The Upkeep was fitted with a self-destruct device to prevent it falling into enemy hands and, shortly after the crash, the bomb exploded, destroying the aircraft.

“The bodies of the crew were taken to nearby Borken and buried in the city’s cemetery.

“After the war, they were all re-interred at Reichswald Forest War Cemetery.”

More aircraft were shot down when the formation reached the Mohne dam but the third successful hit saw the dam breached and Gibson led his remaining bombers to the Eder.

The surrounding hills made for a very difficult bomb run but two more direct hits saw the second dam breached.

The Sorpe dam was also attacked by two aircraft, including one whose Bomb Aimer was George “Johnny” Johnson who was the last survivor of the raid, celebrating his 100th birthday in 1921, but who sadly passed away in December 2022.

Johnson is featured in the movie Attack on the Sorpe Dam, which is released in cinemas later this month.

Just an hour after the last Lancaster touched down at Scampton, a photo-reconnaissance Spitfire took off and brought back images of huge torrents raging through the Ruhr, only the tops of trees and church steeples showing above the floodwater.

Factories, houses, roads, railways and bridges were swept away, and mines flooded as the waters spread 50 miles across the valley.

How successful was the raid?

It is estimated 1,600 people were killed on the ground, 1,000 of them forced labourers from the Soviet Union, half of whom were women.

The cost was heavy for 617 Squadron, too – a casualty rate of almost 40%.

But overall the raid was a strategic success.

It was part of an effort to keep German forces, including Luftwaffe fighters, in Germany and away from the front lines and the vast manpower needed for repair work was unavailable to help construct the Atlantic Wall which would have hindered D-Day.

Also, the images of the broken dams were an enormous boost to British morale, and a savage blow to Germany’s at the same time.

Dr Murray said: “Although the raid has been criticised for the high loss of life, this was not due to the nature of the weapon and was not unusual for bombing missions at this time.

“However, the level of destruction wrought by the small force of Lancasters was truly unprecedented, with many factories, bridges and railways destroyed or rendered unusable by the waters released from the broken dams.

“The Germans went to extraordinary lengths to rebuild the two dams before winter, which shows how important they were.

“With a weapon which seems to defy physics by skipping over water, and requiring exceptional teamwork and flying skills for its delivery, the Dambusters story remains one of the best-remembered exploits of the Second World War.”

Including Newport — where Sgt Kinnear’s name is inscribed on the town’s war memorial.

Conversation