Hundreds were forced from their homes when the Great Tay Flood of January 1993 brought chaos and destruction to Perth and Perthshire.

But for now retired Perth solicitor Richard Blake, the freak flooding also led to the remarkable discovery of documents which confirmed his ancestors’ inextricable links to the Caribbean slave trade.

Discovering family history

Richard was a partner with Perth law firm Condies (now part of Blackadders) at the time of the record floods.

Descended from the Grants of Kilgraston, he’d already inherited boxes of documents from his grandfather and knew he had an extraordinary family history.

Influential figures included Sir Francis Grant, who was president of the Royal Academy, sculptor Mary Grant, and the Earls of Elgin of Elgin marbles and Summer Palace fame.

Salvaged from floodwaters

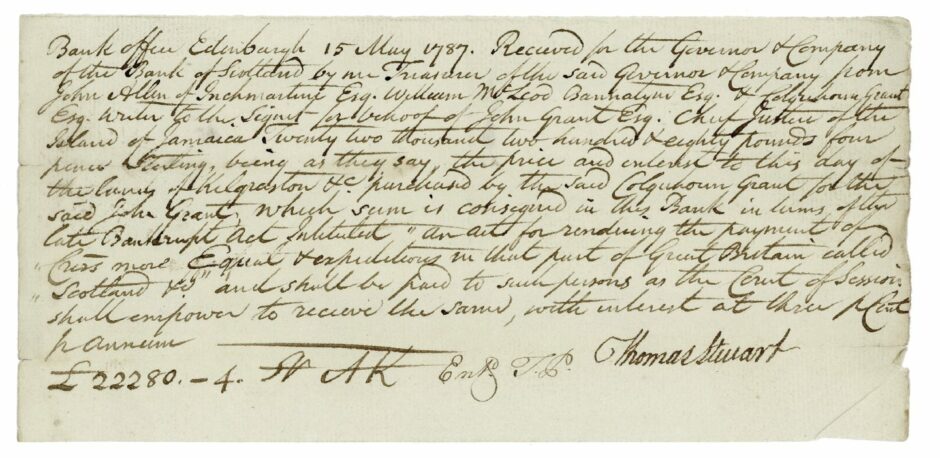

But when floodwaters entered the basement of his offices at the corner of Tay Street and George Street 30 years ago, it led to the discovery of a separate archive marked ‘Kilgraston’ which included a receipt for the purchase of Kilgraston House and estate.

As he pieced together his family history, he was shocked to discover that the Grant family’s fortunes had been built on slavery.

They had deliberately “concealed” this from wider Scottish society while presenting themselves as devout Christians.

“Our office was right at the bridge on the corner,” said Richard, recalling the state of emergency declared in January 1993.

“It was a Saturday night. As the floodwaters rose, the partners were summoned by one of the partners who lived closest to it to come and have a look at the office.

“We had two to three feet of water in the basement of what was the old British Linen Bank building.

“The bank’s huge strong-room which ran under the whole office was the vault for the papers and the title deeds and the wills.

“Condies was established in the late 18th century.

“For whatever reason in the dark corners of the vault there were some papers that had not been looked at for generations.

“A lot of the paper was destroyed – went to the incinerators. A lot of it went to the National Archives.

“But over the next weeks and months, what was left was brought up and had to be sorted out.”

Discovery of ‘lost’ manuscript

As the partners went through the boxes, the office manager, who knew Richard had ‘loose connections’ with Kilgraston, gave him four tin boxes linked to the estate.

A busy life meant it took months for Richard to look at them properly.

But when he did, he came across a manuscript receipt from 1787 from the Bank of Scotland for £27,000 – the purchase price of Kilgraston Estate (between £1m and £2m in today’s money).

It was addressed to Condies, who were the lawyers for John Grant.

Richard was “far too busy as a lawyer and a dad” to look into it further.

It took a further 15 years for him to “knuckle down” and cross-reference with an archive of manuscripts and letters he’d inherited from his grandfather.

But when he did, he pieced together a story that began in Nova Scotia in the 1760s, moving on to the sugar plantations of Jamaica in the 1770s and beyond.

Lifting the lid on history

“The Grants come from Speyside between Tomintoul and Granton-on-Spey,” he said.

“There was a family of reasonably well-to-do Grants with four surviving children.

“In his young teens, John Grant was sent off to London and through links with other members of the clan he got a job with a firm called Robert Grant & Co who were a very young and thrusting firm of merchants.

“You’ve got to think this is the 1750s.

“It’s 40 years after the Union of England and Scotland, and Scotland was just beginning to come in on the back of the colonial expansion.

“Robert Grant & Co set up a trading post in Halifax, Nova Scotia which had been settled only a few years earlier.

“John Grant and one other from Speyside were sent out with a consignment of goods.

“He would have been 15 or 16 at that time. He stayed there for 10 years.

“I’m pretty well convinced he learned his trade as a lawyer in Halifax.

“It was a British naval garrison town.

“Then he moved to Jamaica about 10/12 years later and set himself up as a lawyer.

“He was followed by his brother Francis who had been elsewhere in Canada.”

John Grant made a lot of money rising through the legal ranks and became chief justice of Jamaica.

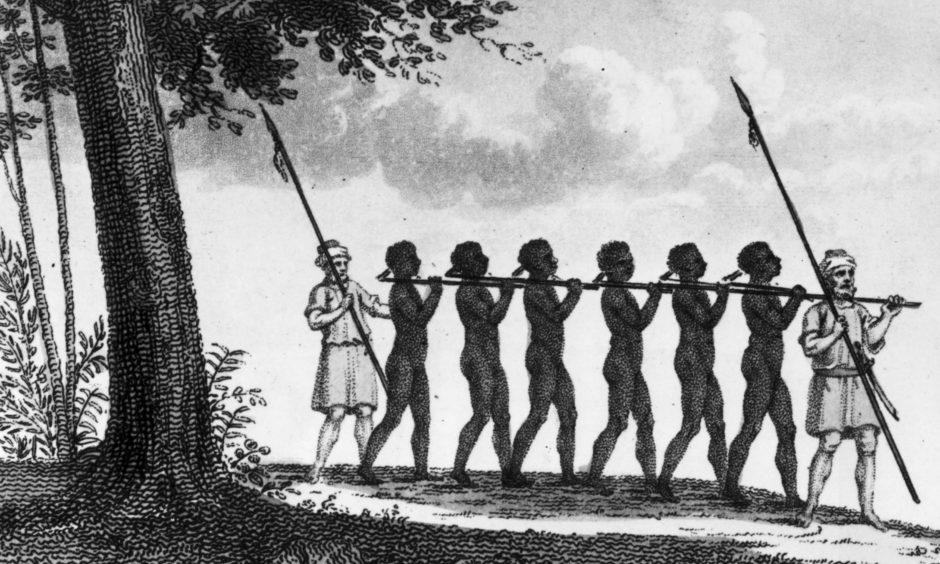

He did a lot of work for ex-patriot landowners from Scotland and England who owned Jamaican sugar plantations.

Making money from slave trade

His brother came in on the back of it and himself became very successful as an agent for ex-patriot landowners.

Francis bought a Jamaican sugar plantation in his own name called Blackness Estate.

It was purchased from Wedderburn of Ballindean (near Dundee).

Francis was directly involved in the slave trade too.

John Grant, meanwhile, had married a widow Margaret McLeod.

When his health began to fail in the 1780s, he wanted to move back to Scotland.

Purchase of Kilgraston Estate

He instructed lawyers in Edinburgh to look for an estate.

They found Kilgraston, which they bought for him on credit, without having even seen it.

John Grant came back to Scotland with failing health in 1790. He died in 1793.

It’s not known if he lived at Kilgraston.

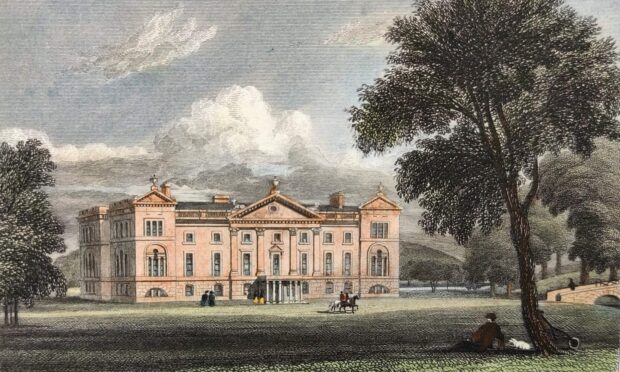

It is known, however, that when his brother returned in 1796, the house was rebuilt to look much as it does today.

It was rebuilt again after being ravaged by fire in the 1870s.

Today, following the break up of the estate and after changing hands, it houses Kilgraston independent school.

In shock news at the start of June, the historic Perthshire boarding school announced it will be closing, amid a subsequent campaign to save it.

‘Awful and tragic’ history

Reflecting on the history, Richard says the slavery links to his family are “really awful and tragic”.

The fact is, he says, that so much of Scotland’s wealth was built on exploitation through the sugar and jute industries.

What’s come out strongly in his research is that the Grant brothers saw it “purely as business”.

What they were doing was legal at the time. It was a “way to wealth”.

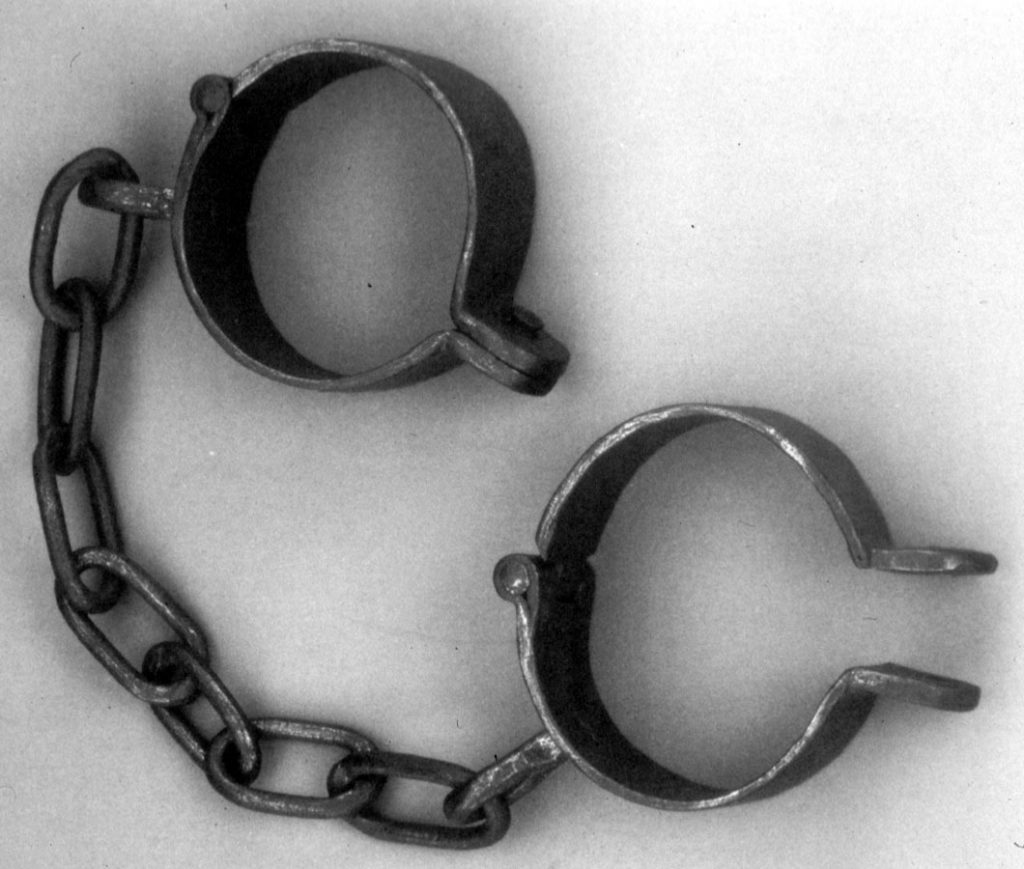

But what he struggles to deal with is that they were also devout Christians.

“Basically they were prepared to conceal in Scotland what was happening in Jamaica,” he said.

“If they had any pricks to their conscience there is absolutely no evidence of that at all. In fact, the opposite.

“There’s evidence that Francis Grant made a point of people knowing that he was supporting various churches in their efforts with the poor in Scotland.

“There’s even newspaper reports that Francis Grant has contributed ‘X pounds’ to whatever.

“But that was the equivalent value of one slave in Jamaica.

“I’m sure that his social rank in Scotland would know perfectly well where his money was coming from.

“I have absolutely no doubt about that at all.

“But I think the expression that comes out is ‘concealed in plain sight’.

“Basically all the trappings of wealth are on show in the house.”

Learning from the past

Richard says there’s no mention of concerns about the morality of slavery until later on when Lady Elgin pressed for the release of a number of slaves in Constantinople.

He finds it “abhorrent” that when slavery was abolished in the 1830s, anyone who owned slaves was entitled to a capital sum for the value of their “property” being lost.

Edinburgh-born Richard, who lives in the Borders and is a writer to His Majesty’s Signet, has now written about the family history in a new book, Sugar, Slaves and High Society.

But he feels there’s “no point” in feeling guilty about it because there’s nothing he can do to change the past.

What’s important, he says, is for him, and for future generations of his family, to understand and learn from the story.

Changed perspective of achievements

“I think what has changed for me is how I now view the generations who went on to great things in the Victorian times,” he said.

“One became the first Scottish president of the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

“He was a famous artist.

“The other was one of the most famous generals in the British Army in the mid-19th century.

“John Grant (3rd Laird) was Master of the Perth Hunt and Captain of two golf clubs: the R and A and the Royal Perth Golfing Society.

“I think what it’s done for me is it’s made me see their achievements through a different prism or lens.

“I have to put everything in the context of where their privileged upbringing came from.

“I think you could call it loosely socially climbing very quickly into the top ranks of the social classes in Scotland and the UK.

“Only through the connections that they had could they have achieved the connections that they did.”

Publication of the book

Sugar, Slaves and High Society: The Grants of Kilgraston 1750-1860 by Richard Blake, will be published on July 4.

Conversation