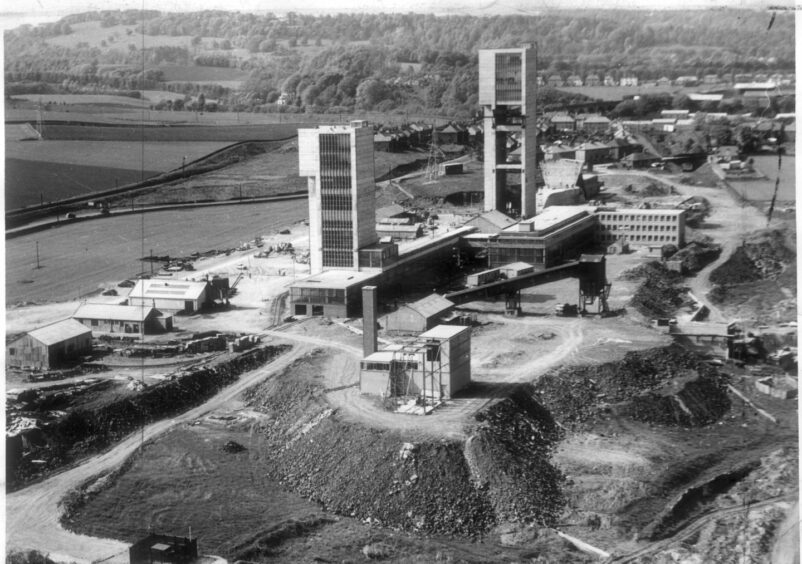

Seafield Colliery in Kirkcaldy closed for good in 1988 after battling through years of uncertainty in the troubled sector.

This was the end of the road.

The former showpiece pit and its 100-acre site were put on the market by British Coal.

These long-lost photographs document the end of a 700-year-old Fife tradition and the subsequent blowing up of Seafield Colliery’s iconic twin towers in September 1989.

When did Seafield Colliery close?

The pit was sunk in 1954 and production began in 1965 under the bed of the Firth of Forth but was bedevilled by geological problems and spontaneous combustion.

The death of five men when the roof collapsed on May 10 1973 stunned the close-knit community and once again highlighted the cost of Scotland’s coal.

Seafield Colliery lost its main coal-producing face through fire during the 1984 miners’ strike and the £3.5m replacement was destroyed by another tremendous blaze in 1987.

The mine’s future hung in the balance until January 1988 when British Coal announced the closure of the once-thriving pit because of low production and £11m losses.

For the 640 men of Seafield there was the bitter irony that buried in its cavernous darkness was a hundred square miles of the finest coal to be found anywhere in Britain.

Kirkcaldy Labour MP Dr Lewis Moonie raised the closure in the House of Commons and questioned why an untouched reserve of coal worth billions was being abandoned.

He said: “Estimates suggest that there are more than 200 million tonnes of coal left in the measures that I am discussing tonight.

“Is it poor quality coal?

“No, it is not. It has the highest calorific value of any coal mine in the United Kingdom.

“It is low in sulphur and chlorine. It is a high-value product when we consider that domestic coal in this country sells at more than £100 a tonne retail.

“That is the quality of the coal that we are talking about.”

Mr Moonie blamed British Coal and, to some extent, Margaret Thatcher’s government and said “there was a failure to invest in the modern equipment that the pit deserves”.

He said: “Can no one see that the quality of the coal that is being abandoned is such that we cannot afford to lose it?

“We have a young workforce — average age, 33 — with no hope of re-employment in an area where male unemployment is well over 20 per cent.

“What does British Coal think it is doing? I do not know.”

Miners remained to seal the pit shafts

What happens when you wind up a pit that helped power the nation?

After the pit’s closure, one of the main jobs for the 640 miners, was salvaging millions of pounds worth of now redundant mining equipment from the labyrinthine tunnels.

The shafts were sealed with concrete.

Some would say that Kirkcaldy has never recovered.

Today, there are very few visible signs of the world that existed beneath the kingdom.

Buyers from throughout the country flocked to the defunct Seafield Colliery on November 24 1988 to snap up some of the disused pit gear.

More than 700 lots of equipment went under the auctioneer’s hammer.

Going, going, gone.

Just like the two winding towers.

Demolition work started in June 1989 on the ground at the site, before the first 144-foot structure came crashing down on September 10 1989 with 60lb of explosives.

The Courier reported: “It took months to build but just seconds to destroy one of Kirkcaldy’s best-known and least-loved landmarks.

“Demolition experts reduced the small winding tower at the former Seafield Colliery to a pile of twisted masonry at precisely 12.45pm yesterday – just as they said they would.

“The 144-foot structure ended its 35-year life in less than five seconds as 60 pounds of strategically placed explosives did its stuff.

“It was a day for believing the end had truly come for Seafield colliery and thousands turned up to witness a sad end to a once promising era.

“In fact, it was all over before most people knew it had even begun – many were still fiddling with expensive zoom lenses or eyeing the 100-acre site through binoculars to see that all the tiny orange jacketed figures had obeyed the five-minute warning siren and retreated to safety.

“A second siren wail went up, many mistakenly thought this was the one-minute warning, then next moment the tower was staggering and a sharp crack told the assembled masses this was it.

“The blast wave was felt even on Seafield hill, a third of a mile away.

“Talk on the hill was of whether the tower would sink slowly then topple sideways, or fall in an S-shape as the experts predicted.

“In the end, it just sort of gave up the ghost and collapsed as cameras whirred and clicked away at a few seconds of history and then there was silence as a huge cloud of dust drifted westwards over an unfortunate nearby smallholding.”

Should Seafield Colliery towers have been saved?

The remaining 203-foot 3,700-ton winding tower was reduced to a mass of tangled steel and concrete by explosive charges seven days later, on September 17 1989.

The towers were gone forever.

Not everyone was glad to see the back of the concrete giants.

Courier letter writer Jim Parker had British Coal and Fife Council in his sights!

He wrote: “After the demolition of the second tower at Seafield Colliery there are certain individuals on whom I would gladly inflict a similar fate.

“The demolition of Seafield is the final stage of a major outrage.

“Closure of the colliery was never justified on technical or economic grounds.

“Nevertheless they were allowed to go ahead with the closure and for that it is hoped that local and national politicians will be held to account.

“The demolition is even worse — the two towers at Seafield are built to exceptionally high standards of strength and durability, and could have so easily been put to alternative use so they could remain an impressive addition to whatever is planned for that area.

“There must be a sad lack of imagination in architects’ and planners’ offices of Fife Council and the Scottish Office.

“Even more outrageous, however, it was not just a case of knocking down the concrete structures at Seafield.

“I went up the towers some weeks ago and was astounded to see that all the magnificent machinery and steelwork was still in place.

“Therefore, we didn’t just see an empty concrete box collapsing; that box contained many engineering “goodies” suitable for use elsewhere.”

Experts once predicted a long and profitable life for Seafield Colliery.

They were wrong.

Two piles of rubble now marked the spot where Scotland’s showpiece pit once stood.

It was the final curtain call in a drama that started back in 1954.

Conversation