There’s something reassuring about the sound and smell of old clocks.

While modern timepieces mark time silently and digitally, old wooden clocks mark analogue time with a rhythmic tick and a tock.

The pendulum swing of a grandfather clock can be strangely hypnotic, while the hourly chime and smell of a simple wooden clock case can transport the timekeeper back to a different era.

Unique Cupar clock exhibition

But what’s it like to find 19 historic time pieces from a single collection together in one room?

The answer can be found at Thomas Young in Bonnygate, Cupar, where A Collector’s Dream is the title of an exhibition spanning five centuries of clock making.

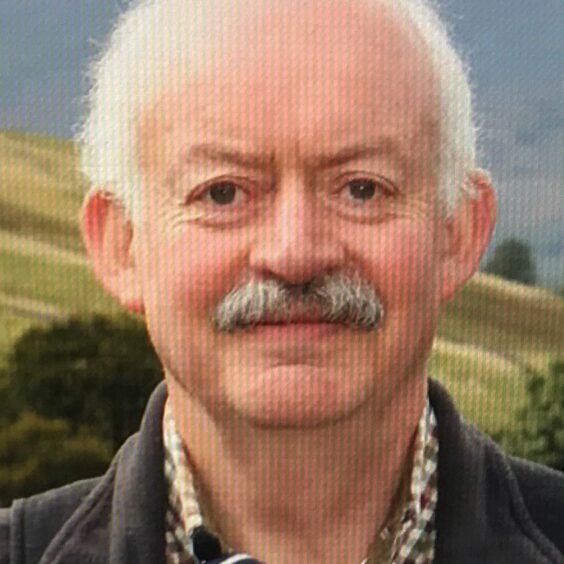

Curated by British Horological Institute member Eric Young, the exhibition features 19 longcase clocks, table clocks, bracket clocks, musical boxes, sundials and barometers.

What are the highlights?

One of the highlights is the Ptolemaic planetarium by Archie McQuater, Edinburgh, c2012.

There are also clocks from Scotland’s father of time, Andrew Broun, Edinburgh, c1695.

There’s a longcase by Joseph Windmills, London, and a musical clock for the Prince of Wales by Russell of Falkirk, c1783.

Also on show are regulators by the Caledonian Railway Company, Reid and Auld, Edinburgh, and Goffe of London, along with two ‘enchanting and important’ longcase clocks by John Smith of Pittenweem.

The exhibition, which opened in April, is due to end on July 31.

Eric, who has compiled a book about the collection, explained that it was “a moment of sadness and fortune” that led to the creation of the exhibition.

Where did the Cupar clock collection come from?

The collection came from the late Dr William Borthwick of St Andrews.

Dr Borthwick was a Thomas Young customer dating back to the early days of Eric’s father setting up the business in 1956.

When Borthwick died in 2020, his widow took ownership of the single household collection and was happy for them to be displayed.

“The title of the exhibition is called The Collector’s Dream,” said Eric.

“On the front page of the book it says Dr William Borthwick’s clocks and other instruments.

“Although within the book I haven’t specifically said where he comes from, it’s common knowledge to a lot of people that that’s William Borthwick from St Andrews.”

Exhibition is a team effort

In creating the book, Eric has collaborated with furniture historian David Jones who lectures at the University of St Andrews; design art director Professor Graeme Pullin from Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design in Dundee and photographer Karen Anne Lamond from Edinburgh.

While the widow has decided she is going to sell all of the clocks – and some have already been sold – they will not be leaving until the exhibition is over.

“This is totally unique because we are standing in a room here of 19 long case clocks,” he said.

“Most people who come here are just blown away.

“There’s two in the room that are not working, but everything else is ticking away nicely.

“Any hour is good. But the 12 o’clock bells are usually special!”

Origins of Thomas Young family business

The Thomas Young story began in 1947 when Eric’s late father Thomas left Bell Baxter High School in Cupar and took up an apprenticeship with his Uncle Robert Kemlo of Pittenweem who had a workshop in Commercial Road, Ladybank.

Thomas finished his apprenticeship with Alex Constable in Kirkcaldy and then served two years National Service in the RAF as a gun armourer.

Thomas started his business in Cupar in September 1956 at 90 Bonnygate.

The outer front shop remains the same to this day.

Over the years, Thomas established himself and found it necessary to expand his front shop for sales of jewellery.

He also expanded backwards and upwards to accommodate his growing workshop.

Initially Thomas carried out work repairing wristwatches and clocks.

This was the highest proportion of his business turnover.

When technology changed during the 1960s and the age of the throw away watch came into being, this did not mean the mechanical watch industry was dead.

But it did change course to become what is now a largely exclusive market.

When did Eric enter family business?

Eric, 60, a former pupil of Castlehill Primary and Bell Baxter High School, started with his father’s business in 1978.

The business operated as a watchmaker and jewellers right up until Christmas Eve 2022.

Run by Eric and his sister Linda since their late father’s retiral some years earlier, the decision was taken to close down the business so that Linda could get her retirement.

However, Eric wasn’t ready to retire.

He took the decision to re-open the shop as soon as he could after Christmas as an antique clock shop.

“Basically in the background for years we have been doing watchmaking,” said Eric.

“But we also do clock-making and clock restoration.

“All of my career I’ve been a clockmaker and watchmaker. But now I just do clocks.”

‘Coincidence’ of exhibition

After he re-opened the shop, having completely gutted it and re-presented it, it coincided with being offered the opportunity to take the complete collection of antique clocks and put them on display.

Like any machine, clocks need maintaining.

They will incur wear and the oil that lubricates the clock generally gets a little bit hard.

They need to be taken apart, washed and cleaned.

They then need to be re-assembled with fresh oil before being delivered back to the customer.

Clocks tend to become heirlooms

Despite this being an increasingly digital world, Eric says he remains “inundated” with work to fix clocks.

Eric said his work revolves around being a restorer of family heirlooms such as pocket watches and antique clocks belonging to families over the generations.

“It’s a generation thing,” said Eric.

“A good deal of the clocks I’m involved with are family clocks.

“People just pass them down like they pass down other things.”

Concentrating on clocks

Eric says the watchmaking side of the industry hasn’t faded away as such.

It remains “vibrant” in the sector.

However, he feels it’s important to “commit to one thing or another” nowadays.

That’s why after a lifetime of fixing watches, he decided to concentrate on clocks for his new venture.

“I was trained as a watchmaker,” he added.

“But at the end of the day after working with watches for 30 years, my decision was that I would prefer to concentrate on antique clocks and pocket watches moving forward.

“That means I don’t work on wristwatches at all anymore.

“I just do clocks and pocket watches.

“The whole process of taking something that’s not working and being able to understand its mechanism and completely dismantle it for servicing purposes.

“Just re-assembling and seeing the customer happy – knowing that the clock is being preserved and that it’s got a chance of presenting itself as a clock and telling the time.

“That’s just a satisfaction there in itself.

“It’s not the kind of career that’s common place. There’s not many clockmakers left nowadays.

“But of those that are, some will not be members of the British Horological Institute like I am.”

What does the future hold?

Eric doesn’t think his son or daughter will go into the business.

They have “other aspirations”.

However, his nephew Jon Reglinski served an apprenticeship under him many years ago.

He’s now a clockmaker and owns James Ritchie & Son (Clockmakers) of Edinburgh.

Despite the modern world, there’s plenty clock repair work to go round.

But he worries that the loss of traditional skills could afflict the industry.

“It’s looking like a very serious problem going ahead,” he said.

“I hate to say it but you worry that’s going to make people just discard their old clocks and think, ‘well, if nobody’s there to fix it in the future, then why should I keep this’?

“I can only do my very best for a customer who’s got a clock that they are wondering about.

“But none of us can really tell what the future is going to bring.”

What’s Eric’s advice to new businesses?

Eric reckons it’s as “tricky and challenging” to open a business in a place like Cupar today as it was when his father did so in 1956.

His advice to anybody who’s thinking about opening up an independent business anywhere is “to be really committed and be prepared to work twice as hard as you thought you might have to, to make it a success”.

He added: “Once it becomes a success you might be able to ease off a little bit.

“But all independent businesses require an inordinate amount of work just to make it successful.”

Where and when to see the clock exhibition

The exhibition, A Collector’s Dream, can be viewed at Thomas Young, 90 Bonnygate, Cupar, Fife KY15 4LB, until July 31.

Opening hours: Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday & Saturday 10am to 1pm, 2pm to 4pm.