The families of the victims of the Piper Alpha disaster received money donated after the Tay Bridge disaster, as the kindness of strangers over a century ago continued to help those in pain.

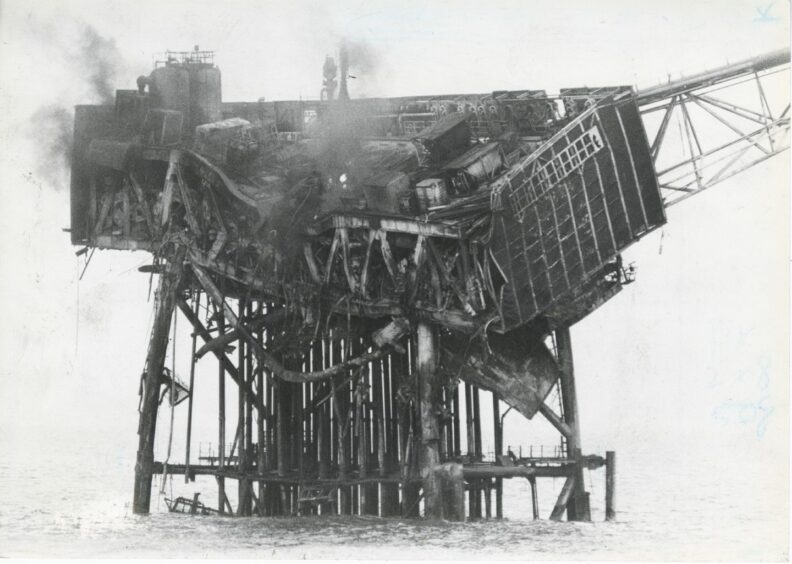

Piper Alpha become known as The Night The Sea Caught Fire.

That was July 6 1988.

It all started with a pump that was missing a safety valve.

After the initial explosion, there were another three massive ones.

At its peak, the heat went up to 700 degrees on the 14,000-ft platform on the remote steel island, which was enough to melt the protective headgear worn by crew.

After the installation was engulfed by flames, 167 men were killed in the ensuing carnage and devastation on a night when everything that could go wrong did go wrong.

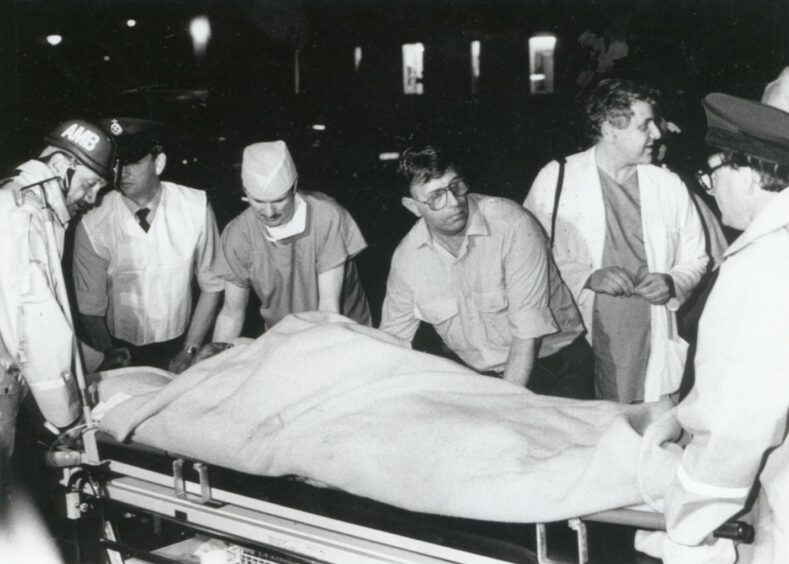

The impact on those 59 who survived was devastating.

They had not only faced an almighty battle to save their own lives, many enduring unspeakable injuries, but had watched as their friends and colleagues lost theirs.

Depression was common, as was guilt and family breakdowns.

Flashbacks where they relived the horrors they had seen and heard, along with smells, were commonplace.

Piper Alpha tragedy scarred communities

Thirty bodies have never been found.

Not a corner of Scotland remained untouched.

The Aberdeen area was hardest hit with most people knowing someone who had been on the platform.

But the disaster also impacted hugely on Tayside and Fife with many workers from the area killed or maimed.

In the days after the tragedy, Grampian Police issued the names of 15 people from Tayside and five from Fife who remained unaccounted for.

Those husbands, brothers and sons never came home and losses were felt in Arbroath, Brechin, Carnoustie, Crieff, Dundee, Glenrothes, Kirkcaldy, Monifieth and Rosyth.

The youngest victim locally was just 24 years old, while the eldest was 51.

The money remaining in the Tay Bridge disaster fund, which was set up after the first rail bridge across the estuary collapsed in 1879, was used to assist the dependants of the men.

The decision to release the £4,000 was made by Lord Provost Tom Mitchell, Dundee District finance convener Peter Court, and finance director Alexander Stephen under the council’s emergency procedure while it was in recess.

The remnant of the Tay Bridge fund was described by Mr Stephen as “interest from interest from the original fund”.

The Courier reported: “The fund was set up by public subscription to help the families of those who lost their lives in the 1879 disaster.

“In 1938, when the fund stood at £600, The Courier reported that its constitution had stated that after there was no further call for the original purpose of the fund ‘the balance could be used to help sufferers through any disaster at land or sea’.

“It seems that by then the last beneficiaries of the fund has already died.

“In 1947 an application to the city council for the money to be handed to the Orphan Institution was kept back by the council in case of a local calamity.”

Mr Stephen said: “It was decided that it was fitting that the money should go towards this disaster, especially because there were so many Dundee people involved.”

The council also decided to add a further £6,000 taken from grant allocation money to boost the city’s donation towards the trust fund recently set up by the Lord Provost of Aberdeen to £10,000.

Mr Mitchell asked council officials to organise a local collection point.

In the days and weeks after the catastrophe, Aberdeen entertained more VIP visitors than would normally be seen over a period of years.

Just two days after the explosion the Prince and Princess of Wales met survivors and rescue services personnel and, later the same day, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her husband, Denis, arrived to see for themselves how the emergency had been dealt with.

Red Adair’s plan to tame the fires

Legendary oilfield firefighter Red Adair also flew in from the United States, but he and his team brought more than words of sympathy.

Despite weather problems and blistering heat, the experience and expertise of the 73-year-old Texan trouble-shooter eventually led to the capping of the blazing remains of Piper Alpha – a job he admitted was probably the toughest and most challenging of his long and illustrious career.

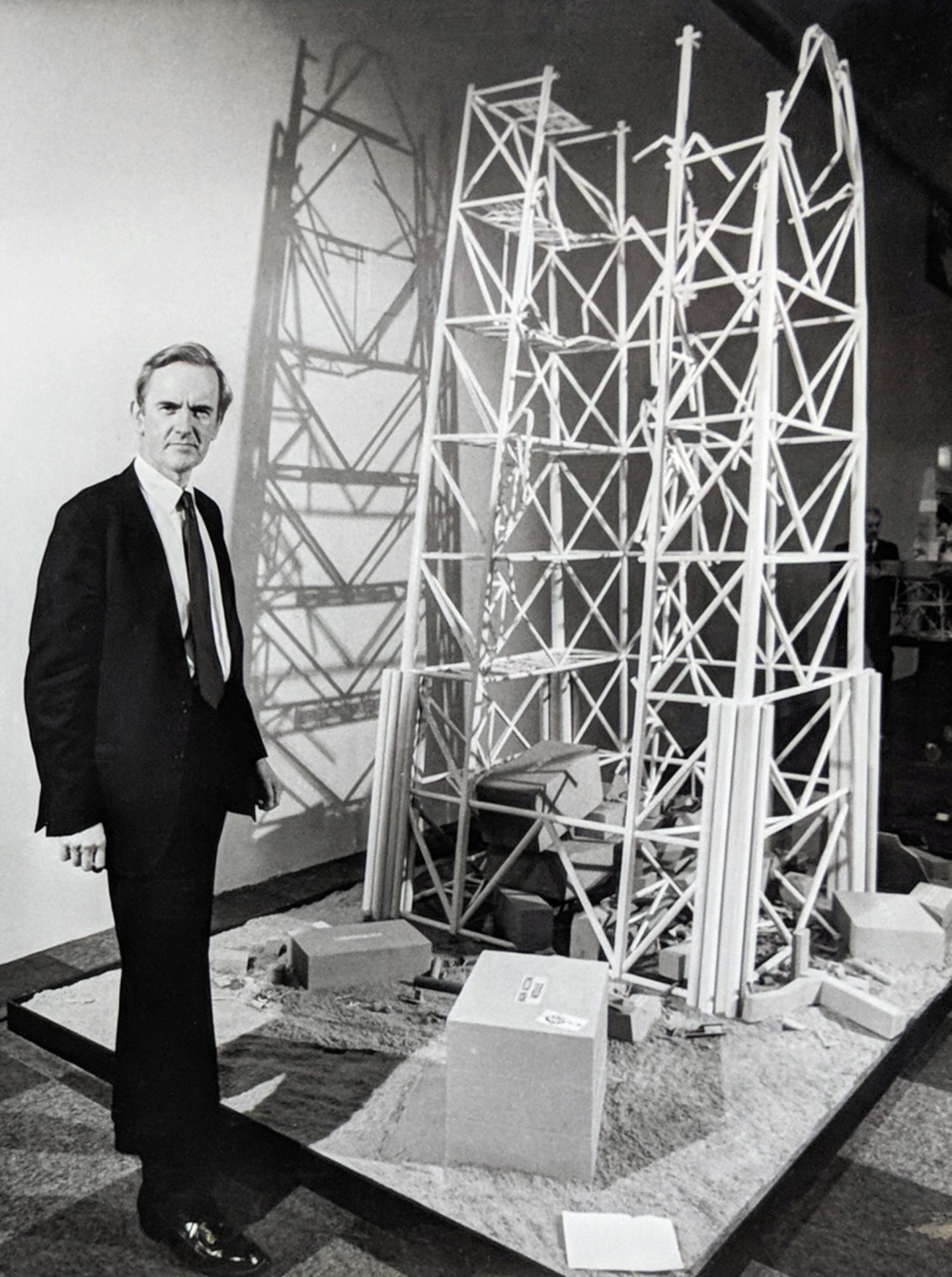

Getting to the truth of the disaster was the mammoth task facing top Scottish legal figure Lord Cullen and his three expert assessors at the Aberdeen Exhibition and Conference Centre – the only venue in the area capable of handling such a massive undertaking.

One Dundee man who lost his life became a very significant name as the inquest began in November 1988 into what had caused the blasts on that unforgettable summer’s night.

Linda Anderson, the girlfriend of 24-year-old Craig Barclay, who was a welder on the platform, claimed he had flagged up fears of a gas leak on the platform up to 48 hours before the explosions occurred.

She said he had phoned her from the platform and told her about his refusal to do welding work because he smelled gas in the area.

Survivor Harry Calder told how at least 100 men died screaming for help in their living quarters after surviving the first explosion.

The helicopter landing officer, who was 35 at the time and lived with his wife and sons in Kennoway, said the men were in the smoke-filled galley where windows cracked under the intense heat.

Mr Calder had been asleep when the first explosion ripped through the rig.

He and a colleague then climbed on to the roof of the helicopter deck before the second blast hit.

They made their way to the pipe deck and lay under a steel table for protection.

But when the floor collapsed beneath them they were left with a choice – stay where they were and risk certain death or jump 100 feet into the flaming water beneath them.

They chose the latter – what they saw as their only option – and floated using life jackets they found in the water.

A supply boat came back for them and they were scooped out of the water.

Mr Calder suffered terrible bruising and burns to his hands.

But he felt grateful to be alive.

‘We all went into Dante’s Inferno’

Lord Cullen’s 180-day inquiry into the disaster found that a pressure safety valve had been removed from a gas pump, through which gas condensate was fed.

In the winter of 1990, following the publication of the extensive Cullen Report, Fifer Charles Haffey was one of seven men awarded George Medals for their bravery.

He and his fellow crew members jumped aboard their fast rescue craft and went to the platform several times to pick up survivors.

On their final trip, they found men clinging desperately to life rafts and debris, many of them grievously burned.

He said: “Nobody was any more or less brave than the others.

“We all went into Dante’s Inferno.

“Some of us came back; others didn’t.”

Occidental, the operators of the platform, paid out £110 million to survivors and families of victims.

A total of £1bn was spent in improving safety in the aftermath of Piper Alpha and the industry continues to spend that much each year on safety improvements.