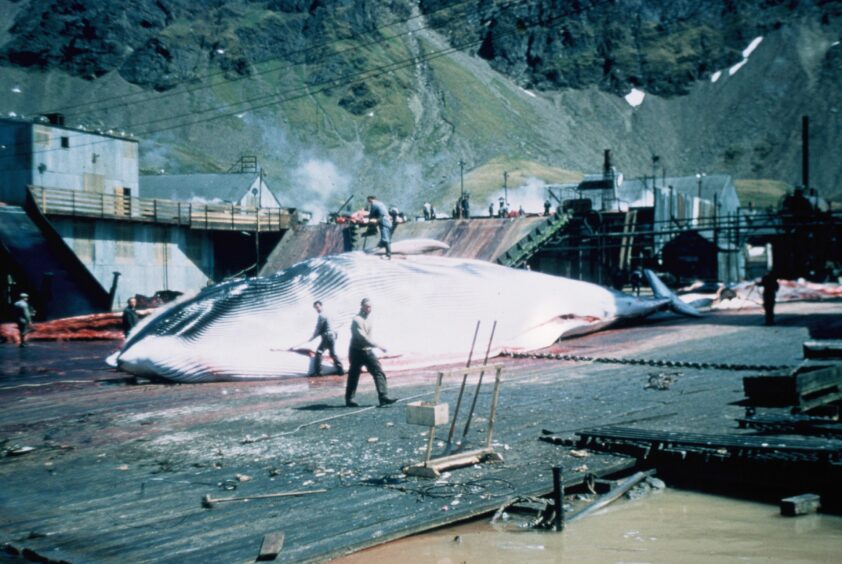

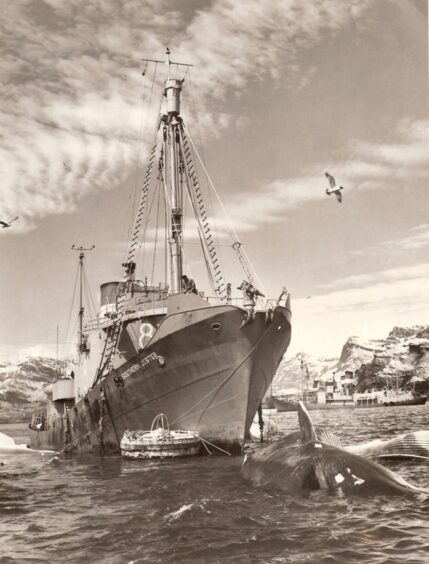

They are the historic images that give an insight into the processing of South Atlantic whales on an industrial scale.

The Flensing Plan at Grytviken Whaling Station on South Georgia, in the South Atlantic Ocean around 800 miles from The Falkland Islands, was at the epicentre of whaling operations for decades.

Records show that 175,250 whales were killed and butchered in factories across the island from 1904-1965.

More information sought about whalers

But while the iconic images are striking, what was life like for the Dundee whalers who worked there?

What did the whalers do in the evenings? Where did they live? How did they contact home? What were their families at home doing?

With many Shetlanders working crofts in the summer and heading to the South Atlantic in the UK winter, how did this constant grafting impact on family life?

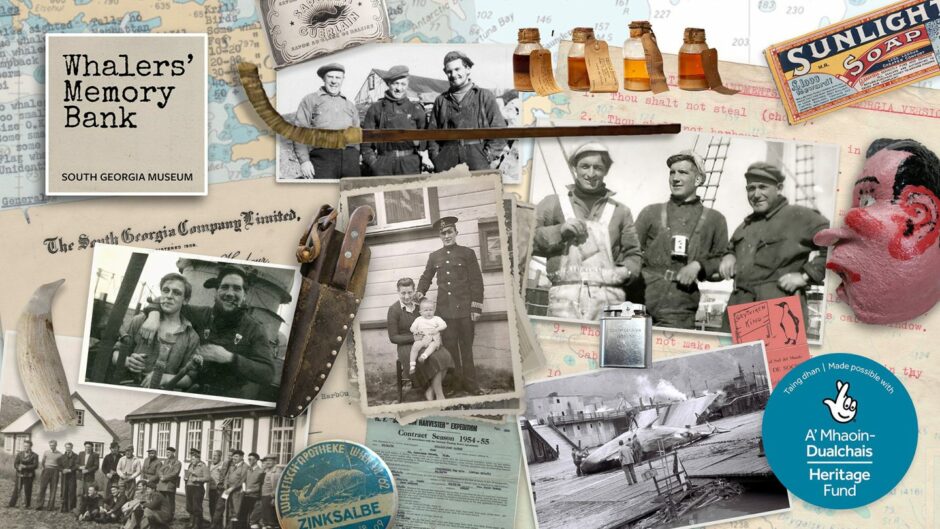

Launch of Whalers’ Memory Bank

Dundee-based charity the South Georgia Heritage Trust is launching a new project to capture the memories of Scottish whaling communities.

Over the next two years the new ‘Whalers’ Memory Bank’ will be created, forming a living digital time capsule which will showcase stories from veterans of the whaling industry, their families and communities – hailing from all parts of Scotland.

The stories will be shared and stored in the Whalers’ Memory Bank, uncovering a previously hidden part of Scottish social history.

Controversy surrounds the story of modern whaling in the southern hemisphere with British companies playing a key role in the industry.

These companies had a largely Scottish workforce and attracted many working-class men with the promise of adventure and competitive wages.

Now, with only a dwindling number of men surviving with first-hand memories of this industry, it’s hoped their stories, knowledge and personal collections will be recorded before they are lost forever.

Whalers’ strong connections with Scotland

At the heart of the project will be a series of community events to gather stories.

It will also make the connection between why whaling happened, where it happened – a great deal of it on South Georgia – and where most of the whalers came from in Scotland.

In an interview with The Courier, Jayne Pierce, project director and curator at the South Georgia Museum, said the project came about after she realised it’s hard to find out about the history of whaling and the people who worked in it.

“During Covid-19, I received quite a lot of emails from various people that had been looking through the belongings and old photo albums from people who’d passed away,” she said.

“People were asking me for information about whaling in South Georgia.

“If I knew of their father or their grandfather.

“I realised that we don’t actually have that much information about the people who were working on the station.

“We’ve got lots of information about the process, about the industry.

“We’ve also got lots of information about the government perspective and how the island was managed and how the magistrates worked.

“But actually we didn’t have much information about the people – especially all of those guys from Scotland.

“We realised there was a big gap in the history.”

Difficulty accessing information

Jayne said when she started researching in Scottish museums, she discovered they did have information.

But it was mostly locked away in cupboards and data bases and was hard to penetrate.

Jayne said this led her to have “lots of conversations” with curators.

However, for a “normal” person living in Dundee, Leith or Shetland who wanted to know more about their relatives, it was hard to dig information out.

She also discovered that a lot of the photographs that do exist are very formal.

They tend to be from the government or industry perspective, selling whaling as a product.

That includes the flensing images of blubber being cut from the whales.

However, there were no photographs of the men in their bunkrooms or in their houses or working in the factory.

Taking a new approach

“That’s when we thought about the idea of trying to harvest, to gather that information, and obviously the best way to do that is to chat to the community,” she said.

“We tried to do that on our own.

“But we realised it was actually a bigger project.

“The Lottery Heritage Fund came up with this great fund that we could apply for, because being in South Georgia, although it is a British Overseas Territory, we are not eligible to apply for lots of funding in the UK.

“This was something we could go for. So we went for it.

“I remember it was in April: we got a phone call to say we’d won the money, £170,000, which was super exciting.

“We really really didn’t expect the money at all because it’s notoriously hard to get.

“It means that now we can actually employ other people to help us do this.

“We can reach out to communities.

“We can run some community events.

“And then if we are successful and manage to get stories and photographs and histories, we can then get a creative producer to create a digital memory bank so to speak that I wouldn’t be able to do myself.

“The other exciting thing is we are working with several Scottish museums which also gives us capacity to reach out to museum audiences as well.”

Hoping for more Dundee whaler stories

Since going public, Jayne says they’ve already had a lot of emails.

They include contact from a 92 year-old ex-whaler and a 96-year-old who was in the Royal Navy and visited South Georgia.

They’ve also had lots of early interest from Shetland and Orkney.

What she doesn’t have so far, however, is much information about the Dundee men and their families involved.

“That’s what I’m hoping to tap into,” she said.

“I’ve talked to the curators at the McManus and I also do a lot of work with the Dundee Heritage Trust.

“A lot of their history is probably from the 1800s.

“That’s when whaling was at its peak in the northern hemisphere –especially from Scotland.

“And so a lot of their collections revolve around that period.

“But they don’t have as much information about the modern whaling as we call it from the 1900s.

“The first step for me is to not only start reaching out to the communities, but I’m also going to be looking at the McManus and Dundee Heritage Trust collections to see what they have because actually we don’t know what they have.

“They know they’ve got things in cupboards, but they haven’t got all the detail.

“That’s one of the big questions that we are hoping to solve over the next couple of years.”

How big was the South Georgia industry?

A census taken in 1954/55 suggested there were 1,021 people on South Georgia in peak summer.

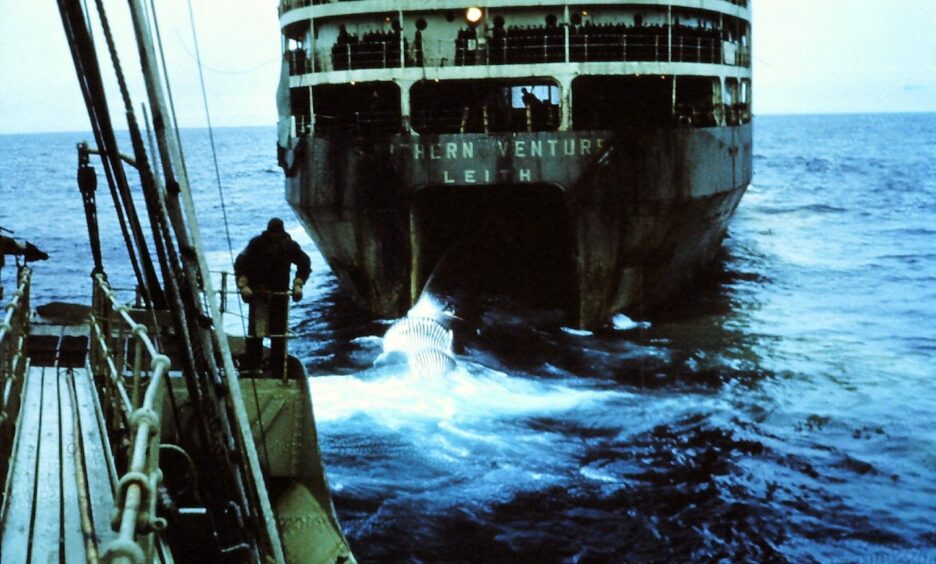

Around that time, Jayne said, 60-70% of the people who worked there arrived on ships from either Norway or Dundee.

Peak arrival time for the whalers was September/October.

This coincided with the whales migrating to feed in South Georgia.

Then at the end of the season in March/April, that whole community would be shipped back north again to Europe.

A very small percentage of men would stay over the South Atlantic winter to do repairs on the factory and some of the ships.

“I think at the peak of whaling there was six working whaling stations and some of them were Norwegian,” she said.

“They would have been mostly Norwegians on the boats.

“For example, Grytviken where the museum sits, was a Norwegian-owned company whereas round the corner there was a place called Leith harbour.

“Leith Harbour was Scottish owned by Christian Salveson which was based in Edinburgh.

“They recruited a lot of their men from mostly Shetland, Orkney and a few smatterings of the other islands such as Lewis.

“There would have been people from Dundee and Edinburgh.

“But there are no facts and figures which is interesting about what percentage that was.

“A lot of them were returning whalers and they would have all set off from Dundee or Edinburgh all at the same time.

“All the ships would go down and back together.

“In Grytviken to give a sense of the scale, in the summer season you were looking at about 400 men working on the factory and out on the whalers.

“That would drop to 60 or 70 in winter.”

How did Jayne get involved?

It’s been a journey of personal discovery for Jayne too.

Trained as a geologist, she has been working in museums for 20 years.

When she first graduated, she wanted to go and work for the British Antarctic Survey.

However, at that time, 1992, they wouldn’t allow women to travel south.

She ended up falling into a career in museums instead.

When she applied for the job with the South Georgia Museum, her experience of working with natural history and geology collections came into its own.

She also feels very lucky to have spent a whole season on the island during her first season and since Covid-19, she’s been back twice.

While she loves travel and adventure and is grateful to her “understanding husband”, it’s a long way to go, complicated to get to and the weather can often be extreme.

“I hadn’t really done much work on whaling,” she said.

“So it was super interesting to learn about whaling and how significant it was across the globe.

“I didn’t really get that feeling about it being a global commodity.

“That was new to me when I first started.

“I didn’t realise the extent of use of whale oil.

“I find it quite amazing that even today the history is still very hidden.

“Not many people know about the extent that whale oil was used and the devastation it caused to the whale population.

“That’s part of the story that I want to bring in as well,” she added.

“When we talk about whaling, lots of people go straight to the barbarity of it.

“The death of the whales.

“I want to balance out that story with that of the men working down there.

“How important their role was in bringing money into their local communities in the UK.

“In a similar way to coalmining or shipbuilding, these guys worked really hard to bring in money to feed their families and keep their local communities going.

“It’s not just about killing the whales.

“I think the idea is to try and create a website that’s easy to navigate, it helps with that serendipity of just browsing and it’s friendly and welcoming.

“But we can still touch on all of those subjects – the positives and the negatives.”

Partnership with Fife and Tayside museums

The project is also a great opportunity to work with a small network of partner museums including the Scottish Fisheries Museum in Anstruther, the Scottish Maritime Museum in Irvine, and Dundee Heritage Trust’s Verdant Works, all of which hold hidden whaling archives and collections that are enlightening, inspiring, and engaging.

As well as supporting with access to collections and stories, some of these organisations will also be involved in the community events the project will be developing for spring 2024.

The Shetland Maritime Heritage Society, Salvesen Ex-Whalers Club and the Shetland ex-Whalers Association will also be collaborating on the project.

Anyone interested in finding out more or getting involved with the project should email memorybank@sght.org

The trust’s Dundee connections

The links between South Georgia and Dundee hook into the whaling and the jute industry, the RRS Discovery, Sir Ernest Shackleton, and in more modern times to Dundee University through their Centre for Remote Environments.

The head office of the South Georgia Heritage Trust (SGHT) is now sited within Dundee’s Verdant Works.

Today, SGHT staff are at the forefront of efforts to preserve the natural and the human heritage of the island, which is a British Overseas Territory.

A feature on the origins of the trust and its role will feature in a future edition of The Courier’s Weekend magazine.