Lost, frightened and alone, Stanislaw Kulik was doing all he could to survive.

Arriving in the city of Tashkent, in Uzbekistan, and finding it swollen with refugees, he was starving and on the verge of dying from hunger.

In desperation, the teenager had no option but to kill and eat a dog.

It was a low point for Stanislaw, known as Stan – and he had endured many low points in his young life.

He was just 15 when his family was forced to leave their home in the village of Obrentchuvka in Eastern Poland and was put on a train to a Russian Gulag in Siberia.

Manual labour

He was forced to do manual labour, such as felling trees, 12 hours a day, six days a week.

Devastatingly, Stan’s mother and younger brother, Mietek, weakened from lack of food, fell ill and died in Siberia. His mother was buried in an unmarked grave.

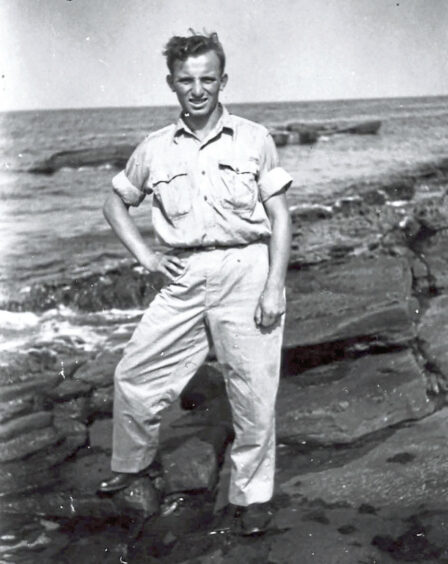

Stan survived the horror of the camp and, at 17, went to join a Polish Army that was being formed in the Soviet Union and embarked on a solo journey through Siberia, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. It would be years before he saw his father and sister Rozia again.

Stan’s story winds across Eastern Europe and Asia, to a refugee camp in Iraq, then to India for a ship bound for the UK, where he eventually landed in Scotland.

He trained as a paratrooper as part of a Polish Brigade in Fife and was later dropped behind enemy lines at the Battle of Arnhem, narrowly evading capture with help from the Dutch resistance.

Memoir

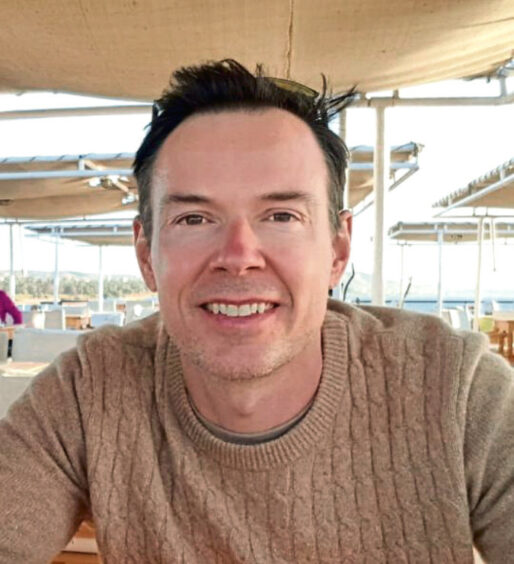

Now, more than 80 years on, Stan’s grandson, Nicholas Kinloch, has helped to recount an early life that plays out like the plot of an epic wartime movie in a riveting new memoir.

“People had come to him before, asking to tell his story but he always turned them down. He wanted it to be shared by someone in the family,” reveals Nicholas, a former St Andrews University student.

“I suppose in a way I’ve always had a goal of writing this book. I remember my grandad telling me some of his stories when I was very young, and I found out more as I got older.”

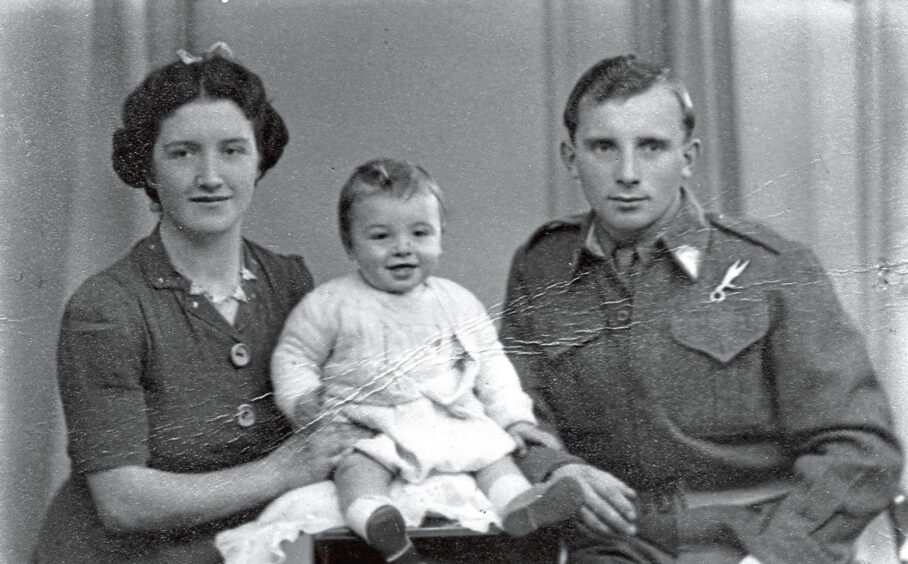

In his book – From The Soviet Gulag To Arnhem: A Polish Paratrooper’s Epic Wartime Journey – Stan recounts six years that took him halfway across the world before he finally settled with his Scottish wife, Isa, in Boarhills near St Andrews, where they lived happily for 70 years.

War stories

Some of Nicholas’ earliest memories of his grandfather were listening to snippets of his war stories.

“There are many remarkable stories from that time but I do think my grandad’s story is unique in terms of travelling solo through Siberia and Central Asia and eventually becoming a paratrooper at such a young age,” says Nicholas.

“He showed incredible courage and resilience.”

He was starving and, in desperation, he had no option but to kill and eat a dog.”

Nicholas, an educational psychologist based in London, began recording his grandad’s incredible war story in 2007. Over six months, he travelled from his then home in Edinburgh to his grandparents near St Andrews.

Nicholas and his grandmother would listen for hours as Stan, then 83, recounted his wartime years with incredible clarity and detail.

“Obviously parts of it were very emotional, especially what happened to his family in Siberia. But, overall, he was happy to talk about it and I think it was cathartic for him.

He really appreciated the opportunity to tell his story,” reflects Nicholas.

Stan passed away in 2016 aged 92, following seven decades of happy family life in Scotland.

Inside the Soviet gulag – if you didn’t work, you didn’t eat

Nicholas’ notes lay untouched for almost 13 years, until 2020, when he found time to record his grandad’s story.

“In the gulag, my grandfather was put to work, aged 15,” he says.

“If you didn’t work, you didn’t eat; and there was never enough to eat. People started to get weaker, and to get ill. His younger brother, and then his mother, fell ill and then tragically died.

“Things were looking hopeless when, one day, news came through that the Nazis had invaded the Soviet Union.

“A rumour started that the Poles could leave the gulags and join a Polish army that was being formed somewhere in the Soviet Union – but nobody knew exactly where it was.

“My grandfather and his older brother left the gulag and started searching for the Polish army.

“They travelled by train through central Asia, down into Kazakhstan. They were very hungry, and had to gather food when the trains stopped; but these trains stopped and started their journeys unpredictably, and at one stop my grandfather wasn’t able to get back on the train in time.

Trying to survive

“By this point, he was lost, frightened and alone. He was on his own for months, looking for the Polish army and trying to survive.

“He arrived in Tashkent, in Uzbekistan, which was swollen with refugees. He was starving and, in desperation, he had no option but to kill and eat a dog. Then, close to giving up, he heard that the Polish army was nearby.”

By faking his age, as he was too young, Stan was accepted into the army. He was taken across the Caspian Sea to Iran, and then to Iraq, where he worked in a camp which helped Polish refugees.

He was there for almost a year, but after Stalin closed the border to refugees, the camp closed down and he was taken by ship to India, and then to Scotland, where he joined up with the Polish Parachute Brigade.

He trained as a paratrooper with the 10th Company, 3rd Battalion, based in Elie and Earlsferry in Fife. He met Isa at a dance in nearby Colinsburgh.

“The Poles settled into the local community and built relationships with the local people,” says Nicholas.

“Many of the paratroopers would later come to build families and settle in Fife, as would my grandfather, and the story of the Polish paratroopers is a significant part of the history of Fife.

Battle of Arnhem

Stan later joined the British 1st Airborne Division and was dropped at the Battle of Arnhem in September 1944.

Around 1,600 British soldiers died during the nine-day assault in the Dutch city, and Stan was, temporarily, one of 6,500 captured British troops.

“My grandfather’s friend was shot in front of him,” laments Nicholas.

“I think grandad was one of the few Polish paratroopers to make it across the River Rhine to support the British paratroopers and ended up in the line of fire.

“When the British forces were pulled back, he was trapped on the German side of the river.”

Evading German capture

The extraordinary tale of how Stan evaded German capture continues to astound Nicholas.

“Grandad was initially captured by the Germans and taken to a makeshift hospital.

“Each day, they’d take some soldiers away, so grandad would hide in the toilet. One of the nurses was actually part of the Dutch Underground and helped him escape.

“She got him a bicycle and Dutch clothes and they cycled right past the guards. Later, they were cycling past another group of German soldiers when the chain on his bike broke.

“He couldn’t tell anyone because he couldn’t speak Dutch, so he had this nerve-racking moment where he had to stop to fix the chain, hoping the Nazis wouldn’t notice him.”

Safe house

After a quick bike repair, Stan and his rescuers eventually made it to a safe house.

“Members of the Dutch Underground hid him in various safe houses before he could eventually get out.

“At one point, Nazis entered the house and he had to hide behind a pram with a coat over him. They were in the room for hours before they finally left,” says Nicholas.

He was later hidden in a hole in the middle of a forest for a few weeks until the Dutch smuggled him and a small group of British paratroopers across German lines in a vehicle disguised as a Red Cross truck to a boat on the River Rhine.

Allied territory

“Grandad said he was so nervous and paddling so fast that the boat was nearly going in circles, but they eventually made it across to the allied territory.

“Helping to retell his story has given me a greater appreciation of the man he was and shown me another fascinating side of him. He was one tough cookie but always happy and kind despite those terrible experiences.”

Years later, Stan would return to the Netherlands to commemorate the Battle of Arnhem and received honorary medals from the Dutch government.

Settled near St Andrews

Following the war, Stan returned to Scotland, married Isa and settled in Boarhills, five miles from St Andrews.

He worked on a farm for many years and later in road maintenance and as a gardener. Stan and Isa were married for 70 years and had two children and three grandchildren.

Stan’s bother, Billy, settled on the Isle of Wight but it was many years before Stan was able to reunite with his father and sister Rozia, in Poland.

He drove from Scotland to Poland in the 1960s to see his family and visited them once more in 2008.

“He knew he couldn’t go back to Poland because of the Cold War and that he’d never see his family again, so he focused everything into building this new, happy life in Scotland,” adds Nicholas.

Nicholas is still trying to trace relatives of the members of the Dutch Underground, to whom his grandfather owes his life.

- From The Soviet Gulag To Arnhem by Nicholas Kinloch, published by Pen and Sword, is out now.