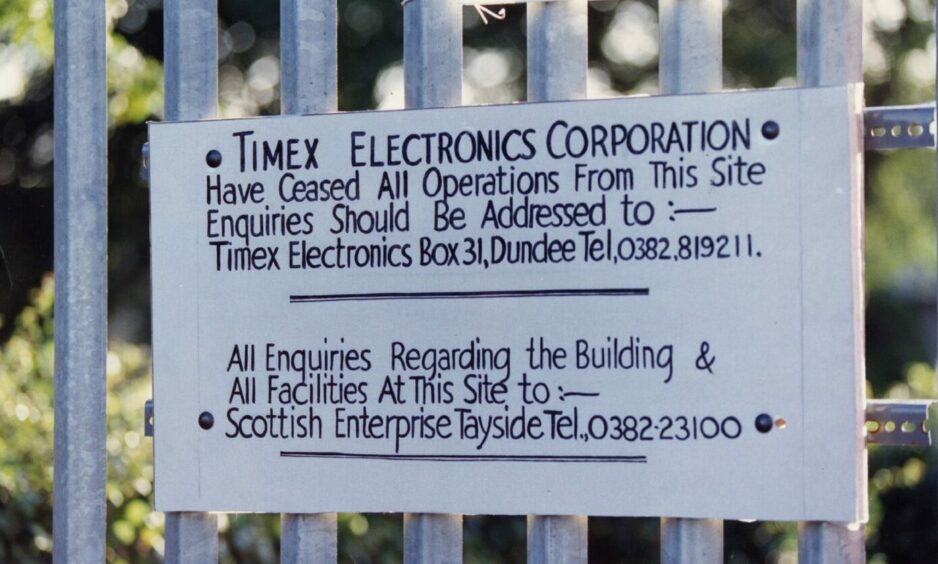

“Timex Electronics Corporation have ceased all operations from this site.”

A hand-written sign on the gates and that was the end of Timex in Dundee.

Timex closed its doors for the last time on August 29 1993, following a six-month industrial dispute marked with a bitterness yet to be equalled in Scotland.

Having stripped the factory of all its contents, the Timex management paid off all its remaining hourly-paid workers before pulling the shutters down at Camperdown.

A brief statement was issued following the closure.

“Weekend shift working ended at 6pm this evening and the plant will not reopen on Monday morning,” read the statement.

“Our orderly rundown of operations in Dundee is now complete.

“The corporation deeply regrets ending its presence in Dundee after 47 years in the city.”

And Timex was gone — almost

The statement concluded by saying that Timex Electronics would maintain an administrative presence in Scotland and could be contacted at PO Box 31 in Dundee.

Telephone and facsimile numbers remained unchanged.

The Courier said: “Timex finally pulled the plug on its manufacturing operations in Dundee yesterday by shutting down its factory in Harrison Road.

“The closure of the Camperdown premises came seven months to the day after the start of a strike over lay offs, pay and conditions which led to the company sacking 343 hourly paid workers in the middle of February.

“The factory – picketed since the start of the strike, and the scene of many bitter exchanges – had been doomed to close since June after 11th hour talks between management and sacked workers’ leaders failed to produce a solution to the bitter and protracted dispute between Timex and the Amalgamated Engineering and Electrical Union.

“Although Timex management indicated at that time the factory was likely to continue in production until towards the end of the year, customers have switched their business to other sub-contractors just as fast as they could, speeding up the eventual closure of the Timex electronics factory.

“The shut-down of the premises at the end of weekend shift-working at 6pm yesterday has meant about 50 more personnel out of the 75 remaining at the end of last week have also now lost their jobs.

“At the company’s peak in Dundee it employed around 7,000 personnel.

“During the course of this year the combination of sackings and now the closure of the Camperdown plant means more than 700 jobs have been lost.”

North East Scotland Labour Euro MP Henry McCubbin reacted angrily to the Timex closure and laid some of the blame at the door of Conservative PM John Major.

“The Timex Corporation, egged on by the British Government, felt they could inflict a humiliating defeat on their UK workforce,” he said.

“What has been shown by this disgraceful episode in UK industrial relations is that there’s a point beyond which working people will not go.

“Mr Major’s government still plans anti-union legislation whilst other European governments realise the future lies in cooperation between management and workforce.”

The Courier featured an article on the history of the plant.

Details of the many successes were printed alongside a timeline of the bitter final days and months of the once-huge Tayside employer.

It started so well.

Triumph and tragedy at Timex

Timex were part of the post-war prosperity boom, the big-shot US company that promised great things and did, in fact, deliver.

Back in its mid-1960s heyday, the Timex facilities in Dundee were massive – 240,000 square feet at Milton of Craigie, 190,000 square feet at Dunsinane Avenue and the flagship factory at Harrison Road was the UK’s largest supplier of watches.

The boom continued through the 1970s with total staff reaching 6,000, though by the end of the decade the US company was being impacted by a global recession and undercut by cheap imported digital watches.

Things started to falter as the 1980s progressed and economic times got tougher and the Milton of Craigie plant was bulldozed in 1988 and Dunsinane followed in 1991.

The Camperdown plant functioned as an electronics manufacturing sub-contractor and cutbacks to a 1992 IBM order saw management seek 110 lay-offs on Christmas Eve.

It was left to line supervisors to select staff for lay-off.

It was the unfairness of the draconian lay-off procedure that caused the dispute.

A mass meeting in the canteen at Camperdown voted in favour of industrial action in January 1993, which was officially sanctioned by the executive council of the AEEU.

Weeks later, Timex management, led by Peter Hall, responded by sacking all strikers – some 343 people – and hiring new workers at lower wages.

Things turned ugly when Timex began bussing in replacement workers.

On Monday March 22 1993, the picket line outside the factory descended into chaos as the protesting Timex workers attempted to block the buses.

The Evening Telegraph printed photographs showing the chaos, with police dragging people from the road, allowing the buses to inch slowly into the factory compound.

Many would be back for what became a regular ritual.

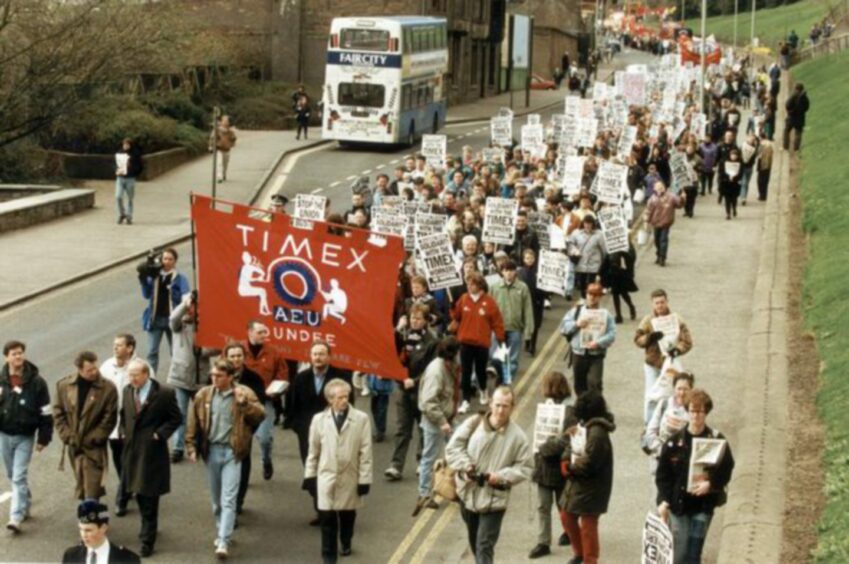

They spilled from coaches and cars which brought them from Aberdeen, Yorkshire, Manchester, Sheffield, Newcastle, and even as far as London.

Scenes from Harrison Road, reminiscent of the Wapping dispute or the miners’ strike, were broadcast round the world, bringing notoriety to the city and sadness to those who had for many years been part of the company’s Dundee success story.

By mid-June, the number of protesters had risen to around 2,500 when Timex executives took the decision to close the Camperdown factory by Christmas.

End of Timex in Dundee ‘sorry and squalid affair’

When Timex finally closed the Evening Telegraph dubbed it the “end of an era”.

It was.

John Monks, general secretary of the TUC, said he regretted the closure of Timex following the David-versus-Goliath battle that left a deep scar on Dundee.

He said: “It is typical of Timex that they, in this very sorry and squalid affair, should have pulled out and done a moonlight flit over the weekend,” he said.

“Timex did not have to proceed down the road they did and there are suspicions in the trade union world that they set out with this particular intention all the way through to pull out of the factory, which has been well supported by public funds and by recognised unions over the years.”

Mr Monks conceded: “We have lost.”

The truth was nobody won.

In fact, everybody lost.