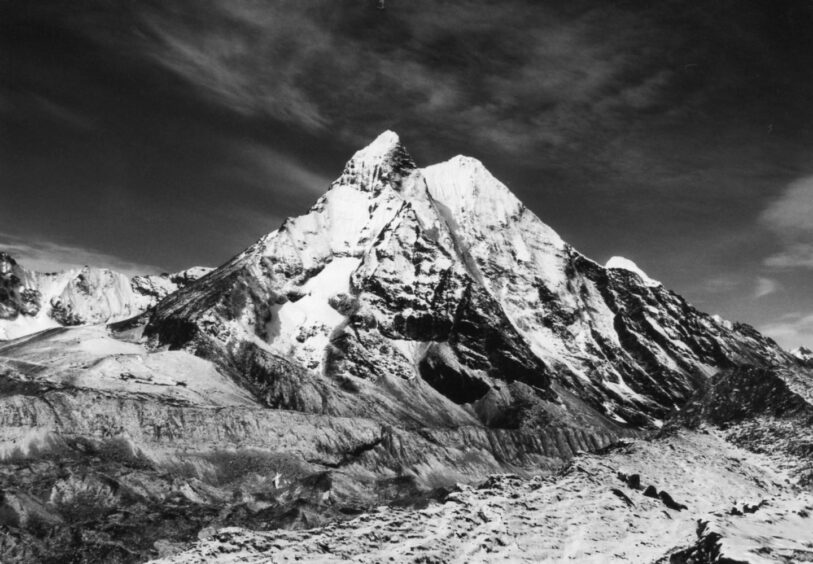

Seventy years ago New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Nepali Sherpa Tenzing Norgay became the first humans to summit the world’s tallest peak, Mount Everest.

Shortly before 11.30am on May 29 1953, the British expedition pair conquered the 8,849 metre (29,032-feet) summit, following years of triumphs and tragedies involving other teams.

The mountaineers spent just 15 minutes at the inhospitable summit – but in the process they became household names.

What is the RSGS doing to celebrate its Mount Everest connections?

On Saturday September 2, the Perth-based Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS) is hosting ticketed tours around its Fair Maid’s House HQ in Perth, inspired by the 70th anniversary.

Visitors will hear stories of adventure from guest speakers and be shown rarely seen pieces from RSGS archives related to some of the greats of Everest and Himalayan exploration.

Speaking to The Courier ahead of the event, RSGS chief executive Mike Robinson, one of the speakers, explained the deep links between Everest exploration and the RSGS.

However, he also put the 1953 achievement into the context of a time when colonial Britain thought it should be leading the world.

“I think the thing about Everest was, Britain with its navy and its empire really felt very strongly that it should be a nation that was setting a geographical first,” he said.

“But it got beat to the first crossing of Greenland by a Norwegian – Nansen.

“It got beat to the North East and the North West Passage, and the North Pole and the South Pole.

“I think that’s why Britain was probably so determined to try and see if Everest was actually conquerable.”

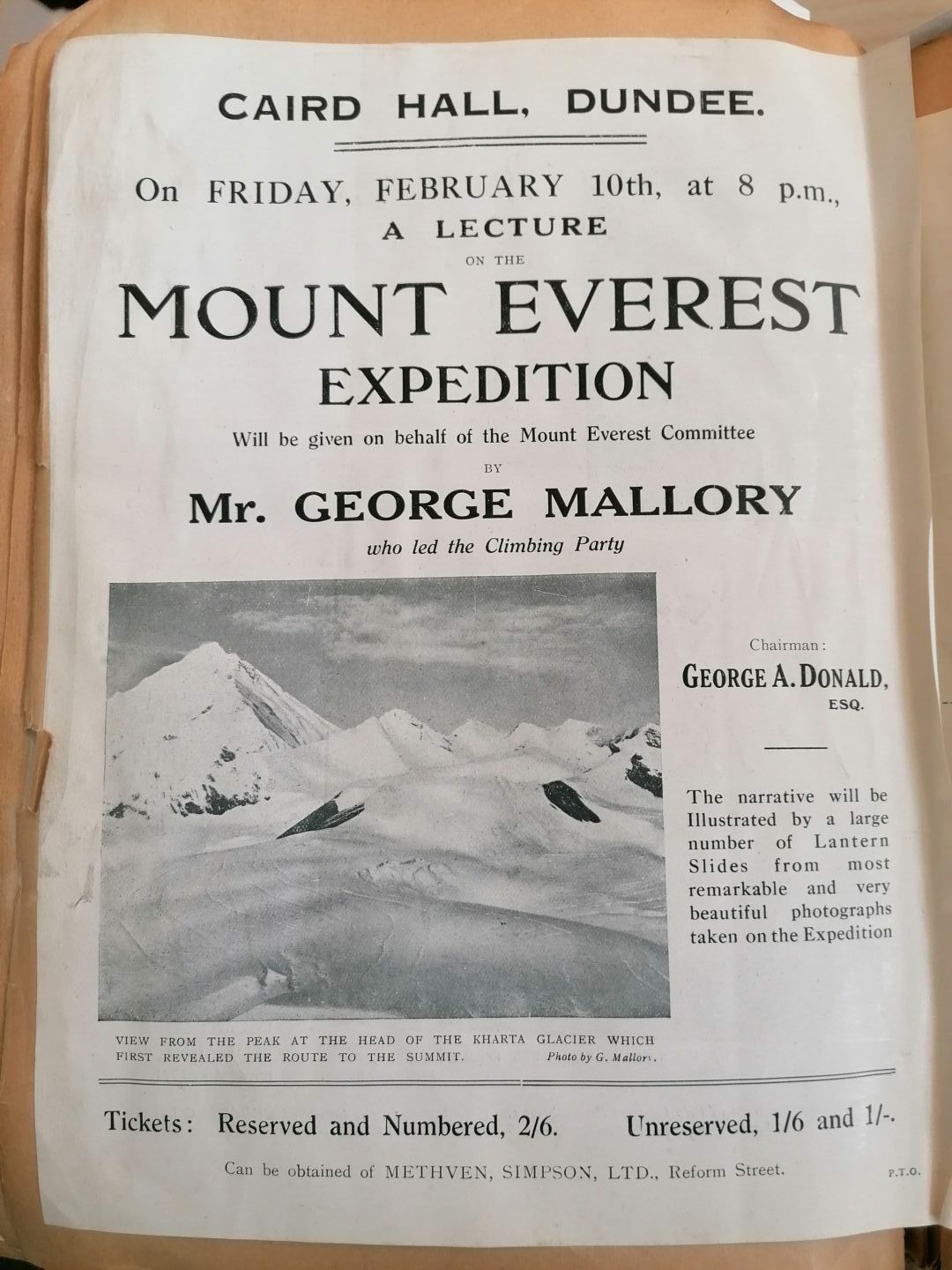

Mount Everest climber Mallory spoke to RSGS in Dundee before he ‘disappeared’

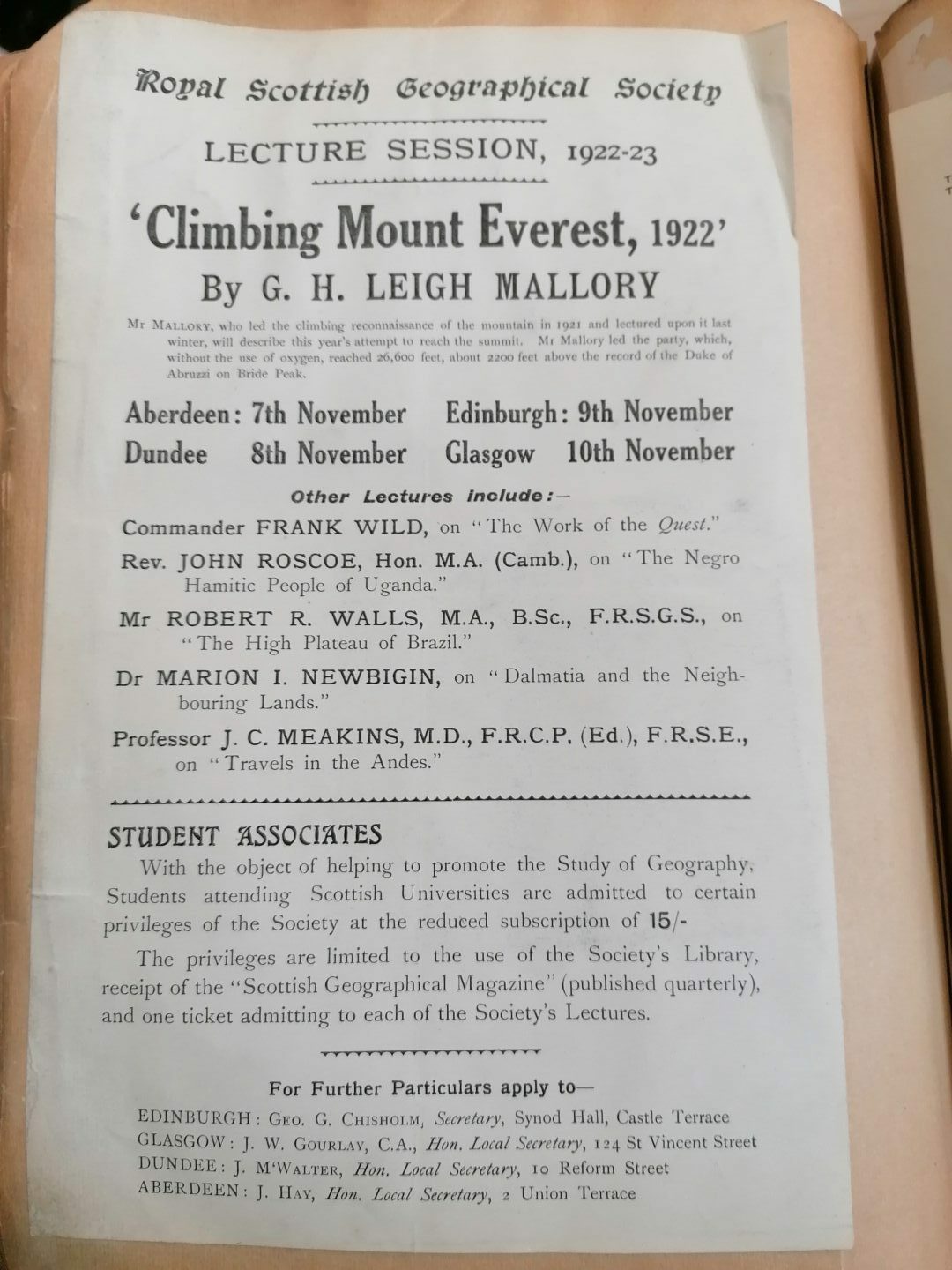

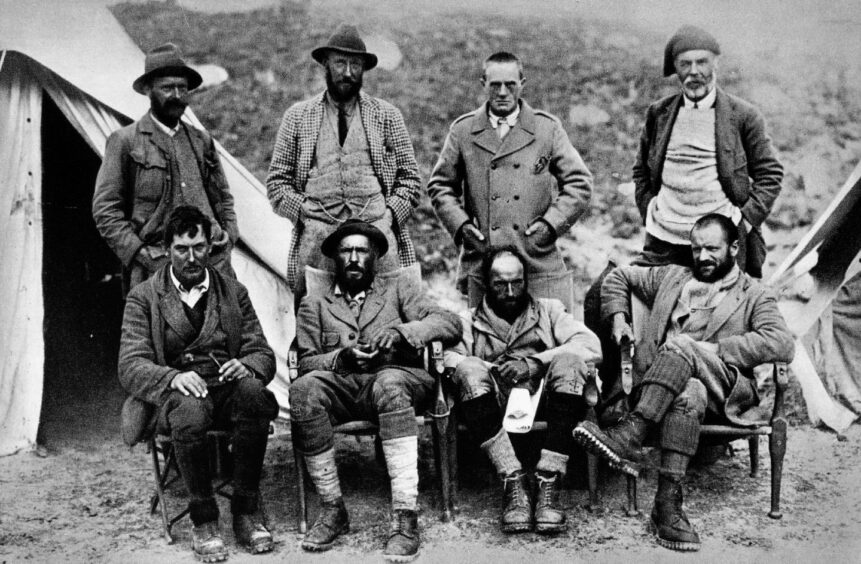

Mike explained that the history really began in 1921.

George Mallory came back from that British reconnaissance expedition and spoke to the RSGS in Dundee, Aberdeen, Glasgow and Edinburgh.

He toured Scotland, using the talks to raise the money to help create the funds to go back.

However, during his 1924 expedition, Mallory and his climbing partner, Andrew ‘Sandy’ Irvine, famously disappeared – Mallory’s body only being found in 1999.

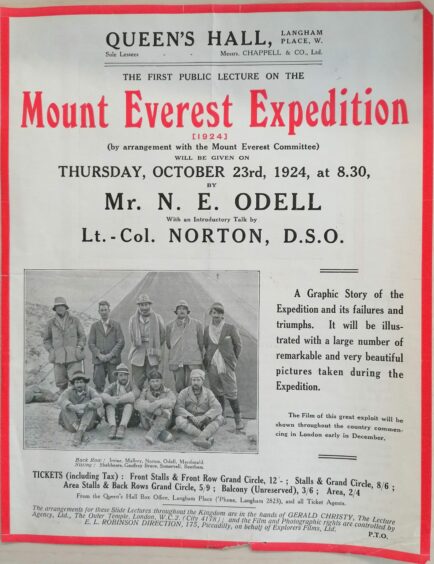

The last picture of Mallory and Irvine alive was taken by Noel Odell on the summit ridge.

There’s been speculation that Mallory and Irvine may even have made it to the summit before their deaths.

When Noel Odell returned home safely, he spoke to the RSGS about his experiences.

What happened next?

“By the early 1950s it was mostly the British and Swiss who seemed to be leading the charge,” said Mike.

“We were almost alternating year on year.

“Famous names like Shipton and Tilman and WH Murray were all involved in these major expeditions in the early 1950s.

“I think it was 1951 that Murray and Shipton and Tilman spoke to the society.

“They were getting slightly further up the mountain. Still finding parts of it impassable. Still struggling. Getting turned round by bad weather.

“In 1952 the Swiss attempted it. They got a little bit higher.

“A guy called Andrew Roche spoke at Aberdeen, Glasgow, Edinburgh about the Swiss attempts.

“It was a fascination for the world at the time.

“Then, of course, in 1953 there was the successful attempt.

“Again, they were speaking to the society later that same year.”

RSGS archives ‘witnessing history’

Mike says the RSGS archive reflects that sense of “witnessing history”.

What they are celebrating now is the mountaineering links with the RSGS before and after 1953 as much as the 70th anniversary itself.

However, while there was healthy rivalry, Mike suggests it’s a myth that the Everest pioneers were trying to out-compete each other.

“There was a famous WH Murray quote that he gave during one of his RSGS lectures,” he said.

“He’d been depute expedition leader on the British Everest expedition of 1951.

“The portrayal of the British establishment was this competitive achievement.

“It was very much who was going to get there first.

“But that really wasn’t how the mountaineers felt, at all.

“Each of them recognised that if you plot the history of climbing of Everest, they found their way in, they found their way up bits of it, they tried different routes, and they each added to each other’s knowledge.

“Murray described it as more ‘baton passing’.

“His acceptance and the whole team’s acceptance in 1953 was that if they didn’t get it, they would add to the knowledge of the Swiss team who might manage it the following year.

“It was actually very supportive – the mountaineering fraternity just wanting to work out if it was actually achievable. That was really their aim.”

‘Extraordinary’ flight over Everest in 1933

RSGS Writer-in-Residence Jo Woolf has been looking at stories shared by early climbers (and aviators) who took on the epic challenge of Everest, with reference to original images and documents in RSGS collections.

She’s particularly fascinated by images from the Marquis of Clydesdale’s “extraordinary” flight over Everest in 1933.

“It’s absolutely extraordinary, what they did,” said Jo.

“They took two bi-planes to India then basically took off in an attempt to fly over Everest.

“If anybody today thought ‘well, let’s go and fly over Everest in an unpressurised bi-plane with the cockpit free to the air’, they’d think they were stark raving mad.

“But that’s what they did.

“The Marquis of Clydesdale, who was based in Scotland, his companion in the same plane was the observer.

“He was tasked with taking the photos. He came and gave a lecture to the RSGS in 1934.

“He gave lots of info about how they managed to do it.

“There’s some wonderful details about that.

“They had a trap door in the floor of his plane and he had to open this in order to point his camera down on to the peak of Everest and take pictures.

“And they were so close – when they opened the door they thought they might catch the tail skid of the plane on the peak of Everest.

“Those kind of stories that they shared with RSGS audiences – they are priceless, really.”

Poignant Everest links during RSGS lectures

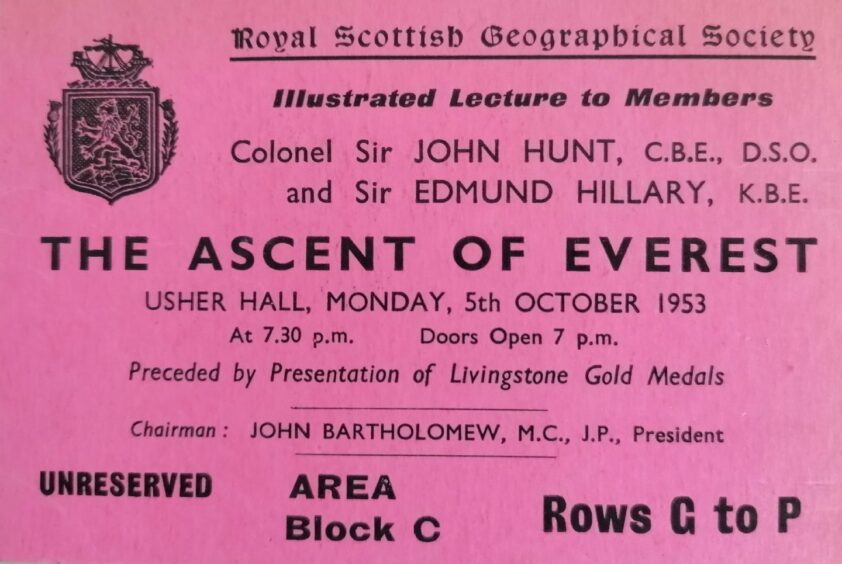

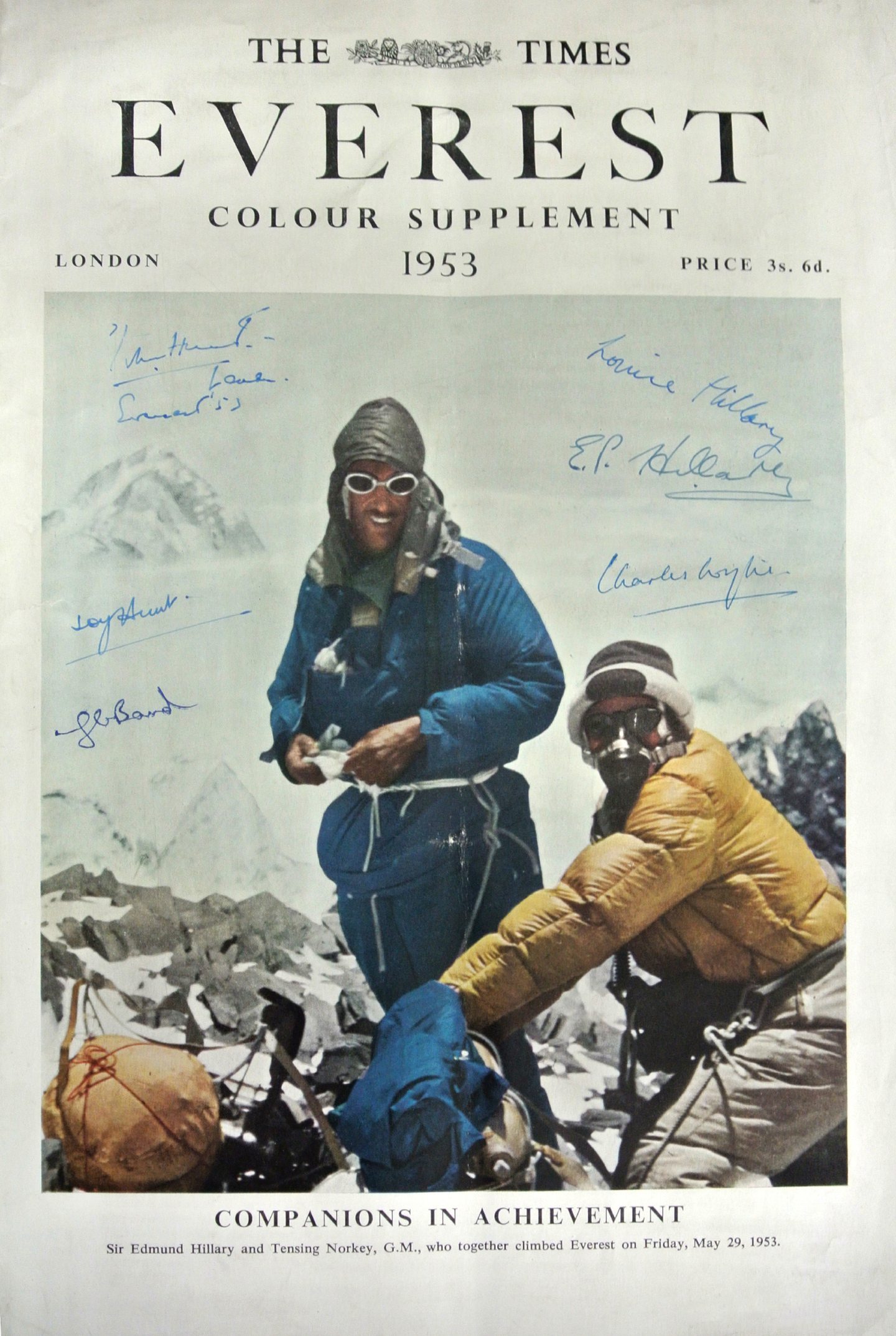

Jo said there’s no doubt that Hillary and Norgay’s summiting of Everest on the 1953 expedition, led by Sir John Hunt, was a “major achievement”.

They gave lectures to RSGS in early October 1953.

They were also presented with the RSGS’s prestigious Livingstone medal.

The archives include detailed accounts of their story, and they have signed posters.

But the archives also reveal some poignant links.

“In the audience at the Edinburgh lecture that Hillary and Hunt gave in 1953, the Duke of Hamilton – who was the former Marquis of Clydesdale – was in the audience,” she said.

“He was the one who’d actually flown over Everest in 1933.

“At their Glasgow lecture, in the audience there was the younger brother of Sandy Irvine who had been lost on Everest with Mallory in 1924.

“He was a minister in Perth. So there’s a real kind of Perth connection as well. It’s really nice because they all link up.

“What’s priceless for me is not just the artefacts, because they are of interest too, but the accounts that we have in newspapers.

“At the time, the newspapers reported what these lecturers said in great detail.”

What were the controversies of the time?

What the archives also do is throw up some of the controversies and debates of the time.

Jo said was a sense that when Mallory spoke to RSGS, there was ambivalence about whether he felt the use of oxygen was the right thing to do or not.

“There was this debate about whether it was kind of cheating, in a way,” she added.

“Some people felt that the purest and the most valiant way to get to the top of Everest was just by pure human physical endeavour.

“Determination combined with physical ability.

“Being assisted by oxygen cylinders that were cumbersome, heavy and prone to failure wasn’t really the done thing – especially in those days when people looked at exploration in a slightly different light.

“Mallory did actually discuss that when he spoke to RSGS.

“He said himself: ‘When I think of mountaineering with four cylinders of oxygen on one’s back and a mask over one’s face, it loses its charm’.

“But he did admit that, in the end, they might have to use it.

“On his attempt that he did actually disappear on, in 1924, he was actually using oxygen.

“It was Sandy Irvine that he chose to go with him – principally because he was so good at actually fixing the oxygen kit that was so unreliable.”

Information abut the RSGS tours in Perth

RSGS are hosting tours on Saturday September 2, as previewed by The Courier, at 11am, 12pm, 1.30pm and 2.30pm, and in each session visitors will hear from four expert speakers.

Tickets are limited. For more information go to rsgs.org/events

Conversation