Like countless numbers of its predecessors, the cargo ship Banglar Urmi docked at Dundee on October 20 1998.

But, unlike the others, the black and red hulled Bangladesh Shipping Corporation vessel’s arrival signalled the death of Dundee’s once-thriving jute empire.

Banglar Urmi had sailed from Chittagong in Bangladesh on June 27.

Initially she was expected to dock in the Tay on September 29, but visits to other ports took longer than expected.

It was only delaying the inevitable.

The end, when it finally came, was without ceremony.

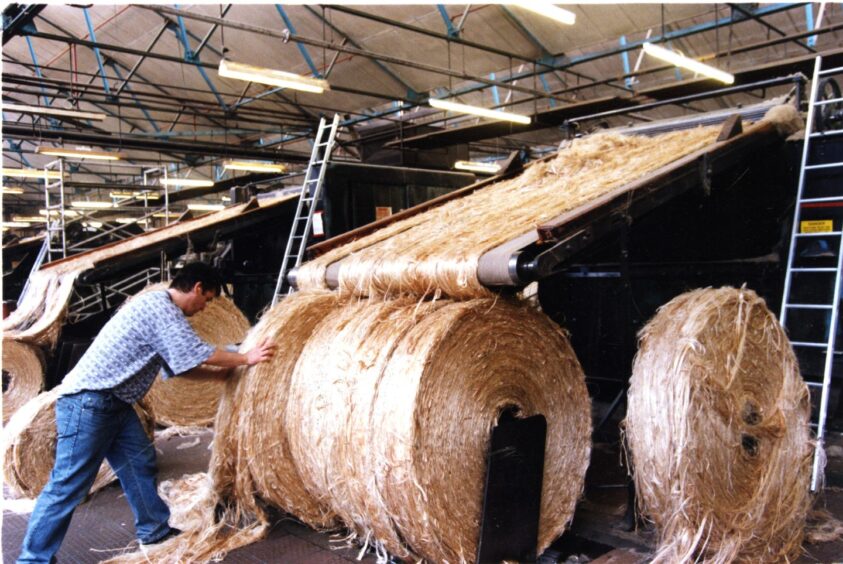

Quayside cranes began unloading 310 tonnes of raw jute from the Banglar the following afternoon, 25 years ago today, which were the last to ever come ashore in the city.

The last of countless millions of tonnes which had arrived in Dundee since 1832.

The bales were destined for Tay Spinners building on Arbroath Road with its distinctive corner entrance lobby that looked like a super-cinema rather than a jute mill.

The credits would roll on an incredible chapter of the city’s history.

Long before becoming the City of Discovery, Dundee was known throughout the world as Juteopolis, becoming synonymous with the three J’s of jute, jam and journalism.

Mills dotted the Dundee skyline in the mid-19th Century, with its famed 282-foot Cox’s Stack at Camperdown Works becoming a landmark.

Other mills included the Coffin Mill and the Seafield Works.

Satirical postcards from the time showed Dundee across the water from Newport as chimneys with smoke belching out.

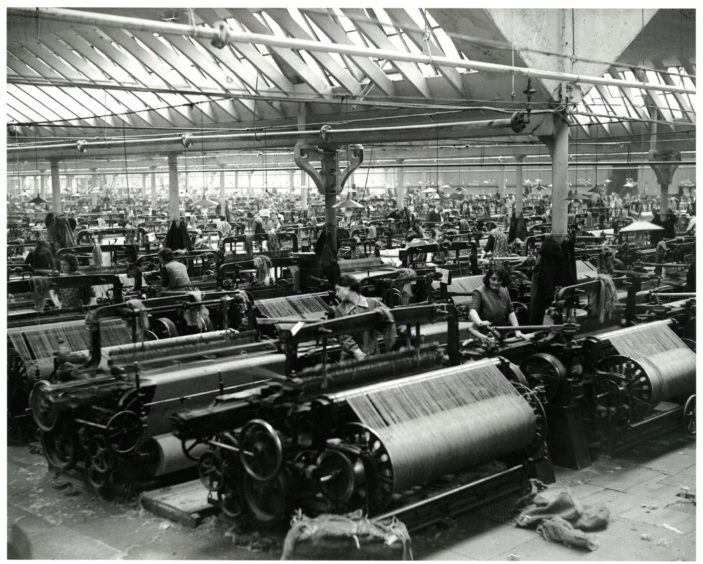

In Dundee’s heyday, 41,000 people or 48.2% of the total occupied population,

and 69.2% of working women, were employed in textiles.

A 50-60 hour week was unexceptional.

The industry was hit by a series of booms and slumps before falling into decline in the 20th Century.

By 1950 there were only 39 jute firms left out of a total of 150 at the industry’s peak, with polypropylene being widely used as the backing for carpets at the expense of jute.

By 1971 only 6,000 jute workers remained in a drastically contracted industry run by fewer than 20 companies.

Camperdown weathered all the storms before closing in 1981 with the loss of 340 jobs.

The end of this iconic works showed beyond question the era of Dundee as a great centre of the textile industry was over.

By 1991 only four mills remained in Dundee and at that point hardly anyone in the city once called Juteopolis earned their corn in the industry.

Tay Spinners was Dundee’s last jute mill

Tay Spinners were left as the sole carriers of the legacy at Taybank Works before they announced in August 1998 that they would be closing with the loss of 80 jobs after processing the final jute shipment.

Chairman and managing director William McLellan said Belgian carpet manufacturers were flouting European Commission regulations and contributing to the demise of spinning in Dundee.

The Belgians were, he said, selling carpets to Eastern European countries under a preference rules scheme which cut import duties on their products.

To be eligible for the scheme, the Belgians should have been using only jute yarn produced in the EU, with Tay Spinners in Dundee the only European source still capable of supplying them with jute in spun form.

But they were not doing this.

“Customs are supposed to ensure that all the materials in the carpets come from the European Union,” he said.

“We should be getting all the Belgian jute yarn business — around 3,000 tonnes at a conservative estimate — but instead we’re getting a tenth of that.

“It’s criminal that a company should be brought down by the pure negligence of the European Commission enforcing their own law.”

Lord Provost Mervyn Rolfe said Tay Spinners’ announcement was “depressing news”.

“It is a sad day to see the demise of one of the last companies that connects the city with jute,” he said.

The Belgian authorities launched a probe into the allegations.

Carpet exports dating back three years were investigated and a new, strict control regime for exports was introduced.

But the investigation came too late to halt the cessation of the manufacturing operations at Tay Spinners.

As things turned out, yarn spinning continued until March 1999 at Taybank Works and some 21 people were still working when the last of the Banglar jute was spun.

Generations of Dundonians mourned its passing when the end came.

“It was very sad, especially, of course, for the workers,” said Mr McLellan.

“It’s the end of an era.”

Equipment taken from Dundee back to India

Tay Spinners was owned by the reclusive Indian jute magnate G. J. Wadhwa, the man behind the 10,000 employee Champdany Mill in Calcutta.

In a final ironic twist for an industry which was destroyed by the lure of cheap labour, the owners imported workers from Calcutta to Dundee to dismantle its machinery.

Once their work was complete, the 19 Indian men boarded a ship at Dundee harbour and sailed back to Calcutta with the power loom machines and equipment.

That was it.

The disappearance of the machines marked the end of an industry that created vast amounts of wealth for the major mill owners and a subsistence level of earnings for thousands of their workers.

All that was left was a heritage museum and bitter-sweet memories.

Gone but not forgotten.

Even today, when the bummers have been silent for years and most of the city’s mills have been demolished or turned into flats, jute remains synonymous with Dundee.

Clatter of looms in Dundee jute mill ‘unforgettable’

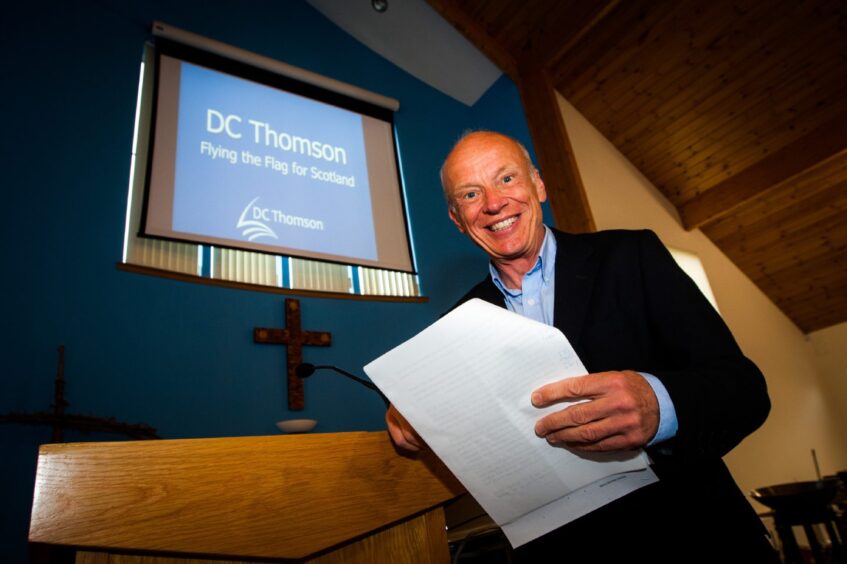

Journalist and historian Dr Norman Watson has never forgotten the physical smell and sound of visiting a jute mill after starting work in Dundee in the 1970s.

“Its one-time forest of chimneys were in the process of being felled, the survivors of 125 works were being rebooted with new businesses, the worst of the slum housing was being swept away – and eventually the clatter of the looms in Tay Spinners was the only sound of Juteopolis to be heard,” he said.

“I walked up from the town, opened a side door and was transported into the age of the endless rows of working people, the women, men and children who made the bobbins fly and the mills bustle.

“Unforgettable.

“What I think is different today to my 1970’s wanderings is that the hitherto trotted-out stories of Dundee in a mist of post-jute decline have now been set aside in media cutting rooms.

“Thanks in part to intelligent and innovative uses of the 50 or so surviving jute mills, the welcome arrival of Discovery, the V&A and other attractions and the achievements of two universities, a pejorative clinging to the city’s industrial decay is no longer the go-to or spontaneous image of Dundee.

“Dundee and history certainly go hand in hand and it is still possible to get close up and personal with the jute era.

“But perceptions have changed and attitudes towards the city have been positively shaped and moulded by many great advances and arrivals.”

A reinvented city of exciting new buildings, award-winning universities, a citadel of science and new industries in a community anchored by the £1 billion waterfront regeneration.

A city transformed since the giant mill machines fell silent.

Conversation