Perthshire-born Sir David Stirling is the name synonymous with the formation of the SAS during the Second World War.

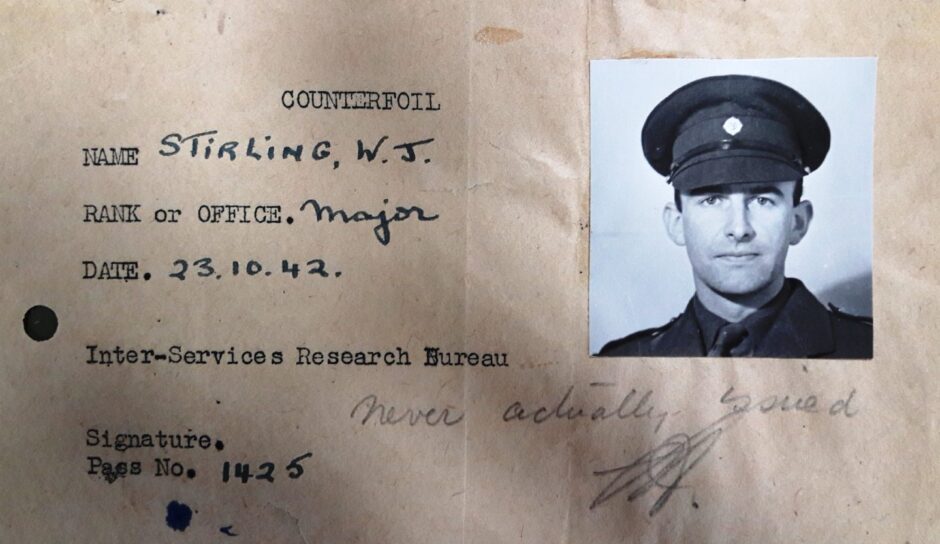

But recently declassified files and interviews with veterans have led to the conclusion that the “real brains” behind the Special Air Service was, in fact, his older brother Bill.

When the SAS War Diary was published in 1946, Bill was described as “a man from the shadows”.

It was an apt description for, unlike his attention-seeking brother, Bill shunned the spotlight.

Now, a new book by writer and historian Gavin Mortimer reveals for the first time that it was Bill, not David, who was the “true founder” of the wartime SAS – despite David’s name being in the spotlight for all this time.

Why was Bill, not David, Stirling the ‘real brains’ of the wartime SAS?

In an interview with The Courier from his home in France, Gavin said the “myth” about David being the maverick genius had been perpetuated by the BBC1 drama SAS: Rogue Heroes.

But it still begged the question – how did the “truth” lay hidden for so long?

“It’s a great question!” said Gavin.

“For 35 years after the Second World War, no one really knew about the SAS.

“Then in 1980, their role in ending the Iranian Embassy siege, which was really the first reality TV caught live, just led to this cult of the SAS if you like.

“It was David who helped perpetuate the myth, and his brother never challenged it!”

What led Gavin Mortimer to write his latest SAS book?

Gavin explained that he’d wanted to write his latest book for years.

2SAS, founded by Bill Stirling, had “forever lived in the shadow” of their illustrious sister regiment, 1SAS, which grew out of L Detachment, the 66 men recruited by David Stirling in the summer of 1941.

When Gavin was writing Stirling’s Men 20 years ago, he had the privilege of interviewing scores of then still living SAS veterans, many of whom had served in 2SAS.

It was their recollections and observations that first made him aware of Bill Stirling and his “outstanding contribution” to the evolution of the SAS.

Last year he published ‘David Stirling The Phoney Major: The Life, Times and Truth about the Founder of the SAS’.

The book explored whether the Perthshire-born officer was a military genius, or a shameless self-publicist who manipulated people, and the truth, for his own ends.

Now in his follow-up book – 2SAS: Bill Stirling and the Forgotten Special Forces Unit of World War II – he focuses specifically on the role of Bill Stirling and reveals the “truth and triumph” of 2SAS.

Bill Stirling held ‘brainstorming session’ that led to SAS founding

“Bill Stirling for me is like the father of British special forces, dating back to early June 1940,” said Gavin.

“On his estate at Keir, just outside Bridge of Allan, he held a brainstorming session with five other leading figures – one of whom was Lord Lovat his cousin.

“They understood that the British were very ill prepared for guerrilla warfare, but, there was a great opportunity because in the inter-war years, there had been huge advances in weaponry, communications and transport.

“Given the state of the war in May 1940 with the Nazis crushing Europe and Britain standing alone, the only way that we could hit back was through clandestine warfare.

“So Bill was in the right place at the right time.

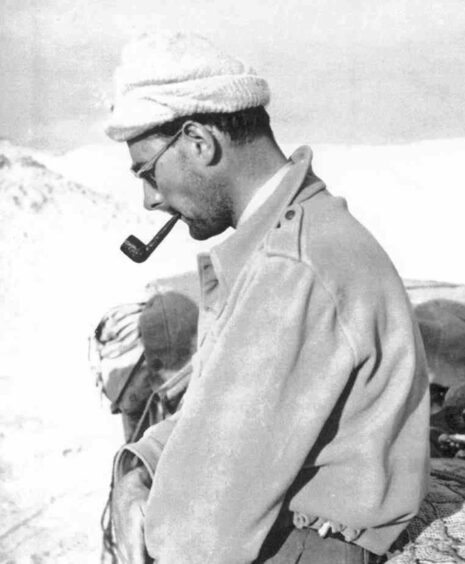

“He went out to the Middle East in early 1941 in the same convoy as David, who was four years younger than Bill.

“David was probably more charismatic.

“A typical younger brother in a way. Just a little bit more rebellious.

“But the more I delved – and this involved a lot of work in the National Archives and going back over my 20 years of research – I realised the founding of the SAS was very much a combined effort between Bill and David, rather than just being about David, who gets the credit.”

Why was David Stirling ‘distraught’ when brother Bill left for London?

Gavin says a “crucial moment” in the story is November 3 1941.

Bill was summoned back to Britain by the War Office – a fortnight before the “disastrous” inaugural SAS raid in Libya that saw 34 of the 55 SAS men who parachuted killed or captured.

David confided in a letter to his mum that Bill’s departure left him “distraught” and that he felt homesick.

This showed how much he “leaned emotionally” on Bill – the more confident big brother.

Without him, he said, David “really lost his way a little bit” and in 1942 the SAS didn’t fulfil its potential.

When David was captured by the Germans in January 1943, Paddy Mayne took over 1SAS.

Bill was sent out to the Middle East to “clear up the mess”.

“One of David’s great flaws was he didn’t really believe in administration,” said Gavin. “His filing cabinet was in his head. So it was complete chaos.

“Bill was sent out there.

“By this time he was in charge of No 62 Commando who were raiding across the Channel.

“He saw the opportunity for another SAS regiment to operate in the Mediterranean, and so in May 1943 2SAS came into being.”

David treated SAS like his ‘private army’

Gavin said another of David Stirling’s flaws was that he treated the inaugural SAS as being like his “private army”.

He tended to recruit people from the same social class who weren’t necessarily adapted psychologically or physically to special forces warfare.

By contrast, when Bill raised 2SAS, he immediately reverted to small-scale parachute operations.

He dropped men deep inside enemy territory in small, two or three-man teams to sabotage railways and attack convoys.

Crucially, when he recruited it wasn’t determined by which school the men went to or who their parents were.

It was whether they had the right psychological make-up for guerrilla warfare.

Bill had a far superior knowledge of guerrilla warfare and what sort of man made the best special forces soldier.

They were resourceful enough to work alone as well as part of a team.

However, Bill Stirling ended up being acrimoniously sacked from the SAS just two days before D-Day.

Why was Bill Stirling sacked from the SAS before D-Day?

“Prior to D-Day, the top brass had intended to drop the SAS just inland from the beachhead, between 15 and 40 miles from the Normandy beaches,” said Gavin.

“Their job would be to block the German armour coming up as reinforcements.

“They would have been wiped out because they were lightly equipped and it wasn’t what they were trained to do.

“A complete misunderstanding of special forces.

“Bill Stirling, when he heard, was livid and argued very forcefully saying ‘no this is the wrong use of the SAS’.

“He argued so vociferously that he was sacked.

“But they did recognise that he was right.

“That operational order was cancelled/abandoned and instead, as Bill Stirling had argued, they were dropped hundreds of miles inland to attack the Germans to blow trains off railway lines, to attack German transport columns as they came up towards the beachhead.

“That’s really what they trained for. So he sacrificed himself if you like for his regiment.”

What did Bill Stirling do after being sacked?

Bill left the army just as D-Day got under way at the beginning of June 1944.

He went back to his Keir Estate as a civilian “washed his hands” of the military.

He took satisfaction instead from being a married family man with estate and business interests in Glasgow and Africa.

By contrast, David was “really a lost soul” after the war.

He went to southern Africa and started a civil liberties group which was well intentioned but badly organised.

While searching for an identity, he wrote his memoir – The Phantom Major – in 1955, which Gavin describes as “50% fact-fiction.”

Bill, meanwhile, was reduced to just four mentions in the index.

But why didn’t Bill say anything?

Bill felt ‘let down’ about Special Air Service departure

Feeling “let down” by the army may account for Bill keeping a low profile.

Gavin reckons another factor was that their dad had died in 1931 and Bill saw himself as David’s “father-figure”.

Knowing of David’s struggle for a “purpose” post-war, he was “quite happy” to let him take the credit.

Bill, having joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in 1940, had also signed the Official Secrets Act, which David hadn’t.

When the Iranian Embassy siege – and the Falklands War – sparked a huge interest in the SAS in the early 1980s, David, as the man credited with founding the SAS, wrote the forward for a “slew of books”.

While he didn’t take the credit all himself, he never credited Bill, which Gavin finds “extraordinary”, even after Bill’s death in 1983.

- 2SAS: Bill Stirling and the Forgotten Special Forces Unit of World War II by Gavin Mortimer is out now published by Osprey Publishing, £25.

Conversation