As a Scottish writer, broadcaster and journalist, Newport-based Billy Kay is best known for his work in promoting and celebrating the Scots language and culture.

Through radio, television, plays, creative writing and especially his hugely influential book Scots: The Mither Tongue, Billy’s work has helped change negative attitudes surrounding Scots and paved the way for its extended acceptance as a key element in Scottish cultural identity.

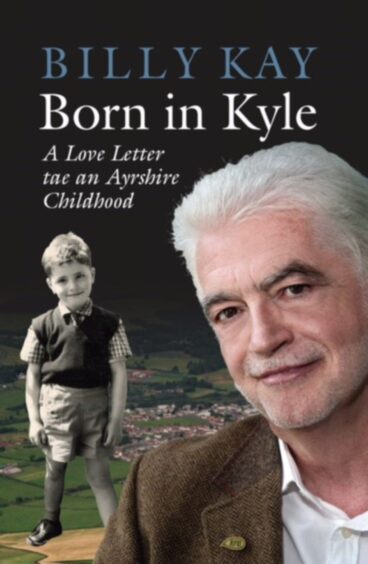

In his new book, Born in Kyle: A Love Letter tae an Ayrshire Childhood, Billy goes back to his own linguistic and cultural roots and celebrates a sense of place and belonging in his native Galston in Ayrshire’s Irvine Valley.

But as he writes about working class family life and the loving environment created by his parents and extended family in Ayrshire, he also shares fond memories of summer holiday visits to his grandmother’s house amongst the mining villages of west Fife.

What was it like for Billy Kay visiting west Fife mining villages in the 1960s?

“My mother was a typical miner’s daughter,” said Billy in an interview with The Courier.

“Both my grandfathers died of lung illnesses in their 60s, so I never knew any of them. I was too wee.

“But my mum’s dad was a pit sinker. He was born in Midlothian, grew up in Mauchline in Ayrshire, then they moved to Bowhill in west-central Fife.

“That’s where her mum and her brother stayed on in Bowhill and that’s where we used to spend our summer holidays in the 1960s.”

Billy recalls how the area still had working pits when he was a child.

Bowhill was a busy place with two picture houses and a “lively community”.

Looking back, he laughs that it was a “great sign of multiple deprivation when you spent your summer holidays in a mining community in west Fife.”

However, it was “different enough” for his younger self to find it interesting.

Billy Kay embarked on an ‘epic journey’ every summer from Ayrshire to Fife

Getting there was an “epic journey” that involved five buses: from Galston to Glasgow, Glasgow to Dunfermline, Dunfermline to Kirkcaldy, Kirkcaldy to Lochgelly and Lochgelly to Bowhill.

Billy recalls how his dad had one suitcase that somehow carried everything for all five members of the family.

However, Billy also remembers becoming aware of the “sing-song” dialect of West Fife.

Billy, who’s now a fervent supporter of Scottish independence, also became aware of, and was influenced by the politics – what he describes today as “socialism with a social conscience”.

Billy’s uncle Tommy – a former miner who ended up driving the Wetherspoon’s bread van – was a “right hand man” for West Fife Communist MP Willie Gallacher who held the seat from 1935 to 1950.

“The Fife miners were even more left wing than the Keir Hardie socialists,” said Billy.

“One of my mum’s earliest recollections was as a wee girl being taught the words of the ‘Red Flag’ by her uncle in 1926 during the General Strike.

“They were part of the culture I inherited.”

Billy Kay would visit the grave of Celtic FC and Scotland legend John Thomson

Today, Billy is a died-in-the wool Dundee United supporter.

But what he used to do every summer on his trips to Bowhill was visit the grave of legendary Celtic FC and Scotland goalkeeper John Thomson.

Thomson, who grew up in Cardenden, was just 22 when in 1931 he died as a result of an accidental collision with Rangers player Sam English during an Old Firm match at Ibrox.

The grave at Bowhill cemetery is still a place of pilgrimage for many Celtic fans to this day.

How did Billy meet the ‘spey-wife’ who predicted Fife mining disaster?

Billy laughs when he thinks back to his teenage years.

As the only “foreign talent” of his generation from outside the area, he says it was great trying to “get off” with the local girls.

Recalling his trips as a 16-year-old to dances at Lochore Miners Welfare, he said the “balancing act” was “how to try and get off with the local lassies and avoid getting your head kicked in by the local young miners!”

It was also at Lochore Miners Welfare, however, that he first met a woman who made two astonishing premonitions that live with him to this day.

The woman, who was the mother of a girl he went out with, was a spiritualist medium.

She had what might now be called the ‘second sight’ or a ‘spey-wife’.

In medieval times, she might have been called a ‘witch’.

She had an ability to ‘see’ things that were going to happen.

“This lady when I visited with her daughter asked me for something that she could ‘read’ – something that belonged to me, where she could almost tell me things about myself,” said Billy.

“I gave her my watch.

“Later on the daughter and I went for a walk and came back.

“The lady started telling me things about myself. I was very sceptical.

“She told me things that were true about me but could have been true about a lot of people.

“She came to one point in the reading of the watch where she said ‘who do you know who’s got a bad leg or one leg or wears crutches?’

“I said, ‘the father of a boy in my class at school has one leg – probably from a miner’s accident’.

“She says – ‘no this is stronger than that, this is someone you’ve seen in the past few days or you are going to see in the next few days’.

“Anyway, I said ‘thank you’ and left it there, said my goodbyes.

“I had to leave to get the last bus from Ballingry to Lochgelly and from there the last bus from Lochgelly to Bowhill.

“I turn the corner to get the bus for Bowhill, realise I’ve missed the last bus and I’ve got about a three mile walk.

“Then round the corner – wait for it – comes a man with one leg and crutches.

“He said ‘we’ve missed the last bus son. Come on. I’’ll get us a lift’.

“A car comes round the corner, he stuck out his crutch, the boy stopped and gave us a lift to Bowhill.”

What did the ‘spey-wife’ tell Billy Kay about a Fife mining disaster?

The other “matter of fact” prediction that the spey-wife told Billy was that there was going to be a major mining disaster under the Forth.

To make it worse, her own husband worked there.

Billy told his dad. Then, about three weeks later on September 9, 1967, when Billy was back home in Ayrshire, listening to music in the kitchen, his dad came in and said: ‘It’s happened Billy.

“There’s been a mining disaster at the Michael Colliery. So many men have been killed”.

Billy says nothing like that has happened again in his life.

He recalls the woman telling him she felt “burdened” by this power. She didn’t want it.

He has, however, since met people from traditional rural Gaelic cultures who had the “same feel” about them.

As if they could “tune in” to something regarded as out of the ordinary.

What else does Billy Kay’s new book written in Scots include?

Billy’s book, which is written in Scots and will also feature an audio version, recalls enduring cold winters in a council house where the only source of heat was a coal fire and a paraffin heater.

He writes about what they ate and drank; about how children passed their time by collecting everything from football cards to war medals; the richness of the Scots-speaking world they inhabited, using words and sayings with a pedigree going back hundreds of years.

He reflects on the influence of American music and movies coming into the Irvine Valley and the strong sense of community that came from a still living mining tradition.

He recalls local religious observation and the good folk from the respectable working class who looked down on the minority who indulged in “ugly sectarian nonsense”.

There’s even a story of the Galston boys organising what they believed might be the last game of football at the time of the Cuban Missile crisis in 1962.

Included in the collection are two short stories and a prize winning poem also rooted in Kyle which were published in anthologies of Scottish literature many years ago, but which are now out of print.

End of an era

Looking back too, Billy realises that his was the last of the pre-television generations.

Life was lived in a strong Scots-speaking environment which would be eroded when television in English was beamed into every household from the early 1960s onwards.

Billy acknowledges Robert Burns in the title of the book – like the bard himself, he was born in Kyle.

But perhaps the greatest influence on this work is from another Ayrshire writer, John Galt whose 19th century work Annals of the Parish gave a vivid account of an Ayrshire parish at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th Century.

In Born in Kyle Billy Kay attempts to do something similar for his own parish and its life in the middle of the 20th Century.

For more information visit billykay.scot

Conversation