Sylvester Stallone’s third Rocky film pitted the Italian Stallion against Hulk Hogan’s Thunderlips in a legendary anything-goes brawl.

Rocky finished off Thunderlips by tossing his much-larger opponent out of the ring before trading blows with Mr T’s Clubber Lang in the 1982 film’s final fight.

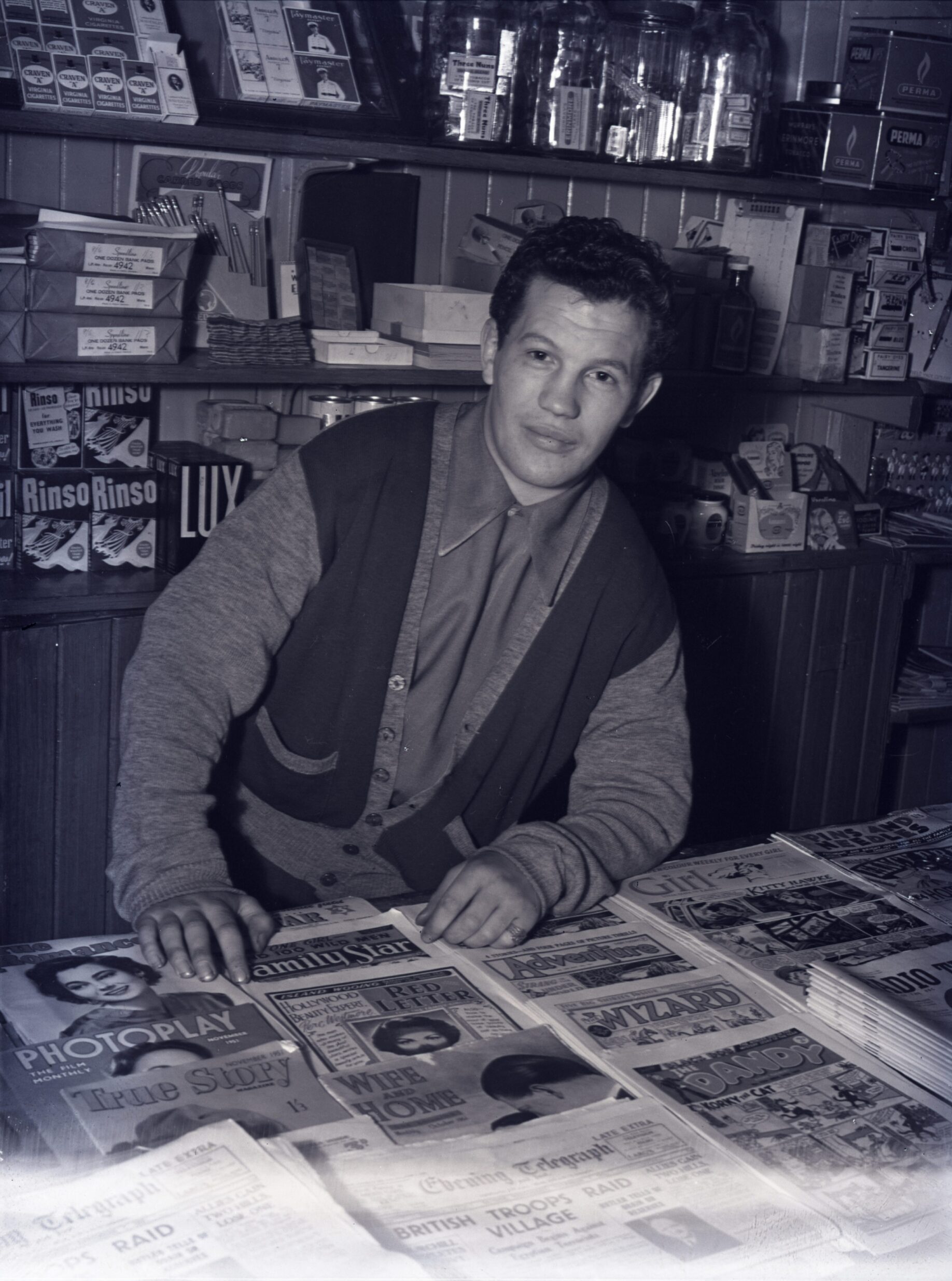

Boxers crossing swords with wrestlers is nothing new and Dundee’s Bobby Boland was the tiger-eyed fighter whose ring clashes with grapplers were box-office.

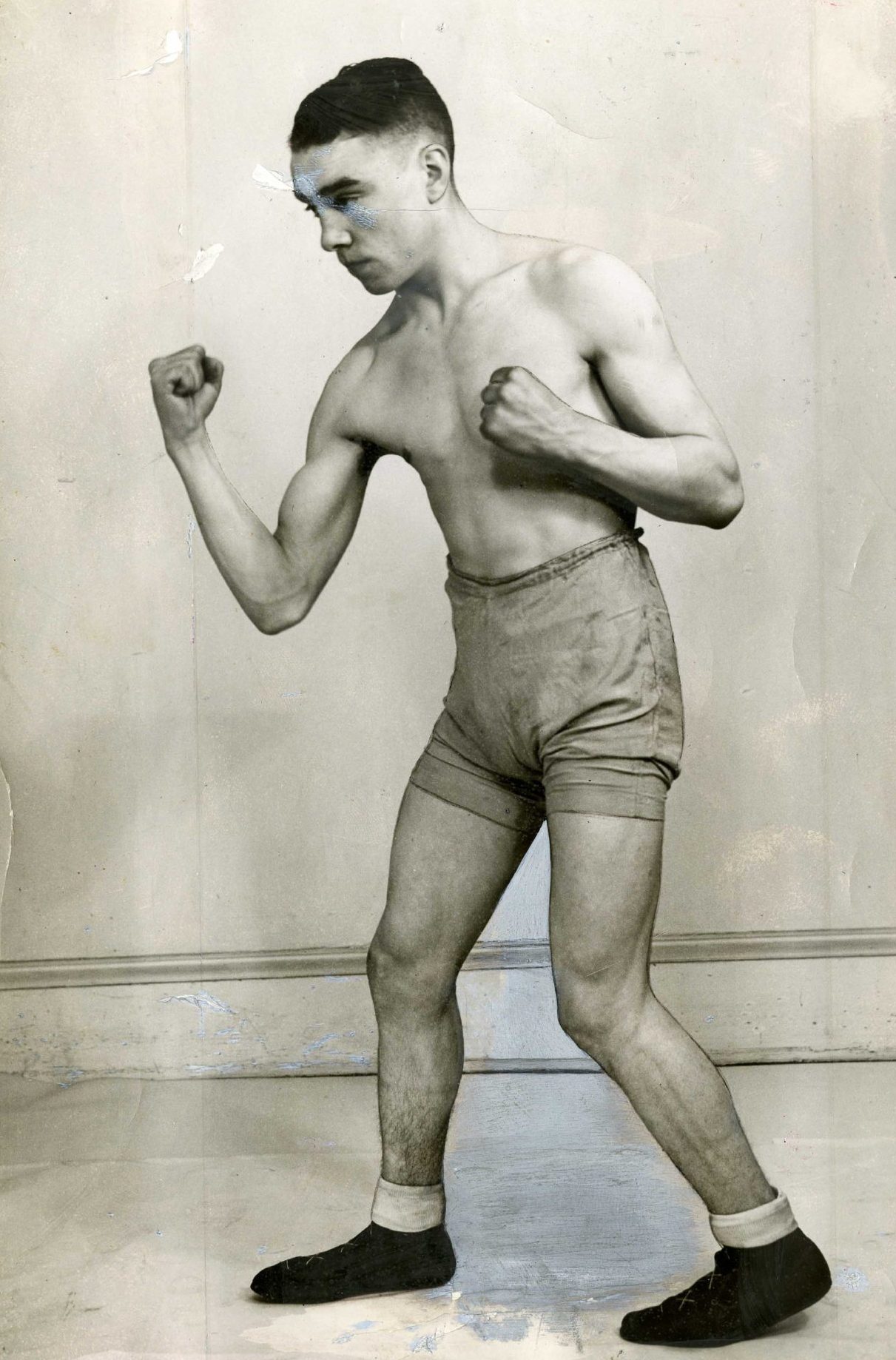

Pity the fool who got in the ring with the tough Dundonian during his 1940s and 1950s heyday.

That’s because the hard-hitting Boland was one of Britain’s top bantamweight boxers post-war before going on to fight pro-wrestlers at their own game.

Boland was born in 1929 into a tough, working-class background.

He idolised fellow Dundonian Jim Brady who memorably beat Richie ‘Kid’ Tanner for his British Empire bantamweight title at Tannadice Park in a blizzard on New Year’s Day in 1941.

Boland started his own paid career against Stan Young in Blackpool.

Idol Brady became his trainer.

Bobby Boland lost money on his first fight

In his 1976 memoir he recalled the purse for his first fight was £8 but his train fare to Blackpool and hotel bills came to £9.

Back home, Boland was quickly despatched to a boxing booth in Paisley to gain experience.

Every carnival had its boxing booth in those days and they were a great attraction.

Boland said: “There were about five professionals of varying weights who would take on challengers from the crowd. If the challengers went the distance they could pick up £4.

“It was a tough life. We had to take on all kinds – brawlers looking for easy money and professional boxers looking for sparring practice.

“The brawlers we could handle, the professionals were a different proposition.

“Once I knocked out the local favourite and his friends showed their displeasure by showering the ring with bottles.

“On another night some of the locals tried to get their revenge for a few defeats by overturning the caravan in which all the professionals lived.”

Boland turned pro aged 16 in October 1946.

He spent the early part of his career training on his own and phoning Tony Vairo, his Liverpool-based manager, to find out what fights he had fixed up.

Vairo had Boland working pretty hard with bouts in the Caird Hall and in Liverpool and Glasgow.

The graveyard of champions…

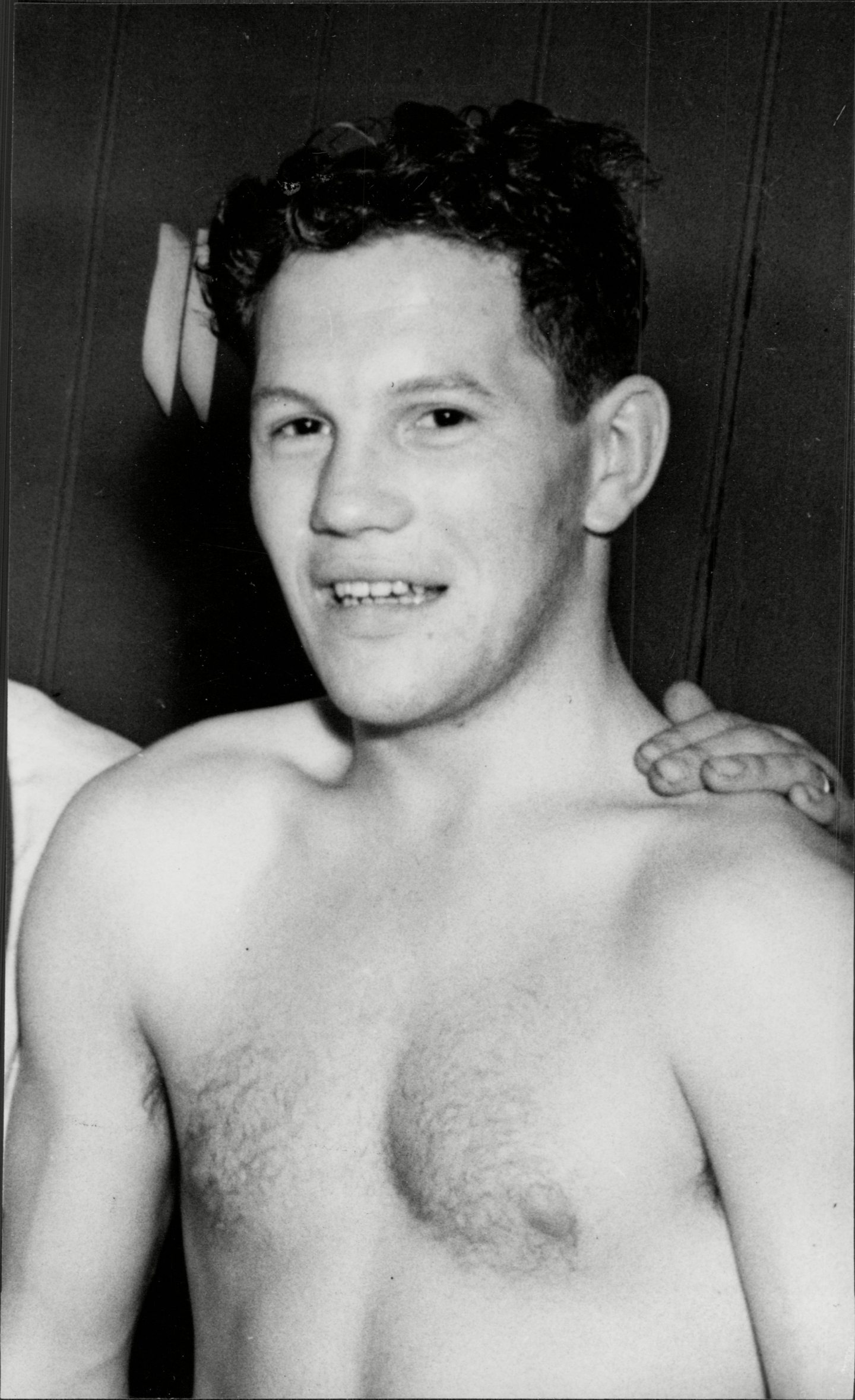

After 16 fights as a pro he chalked up 16 wins – 10 by knockout.

Then he received a KO blow when he was called up for National Service with the RAF.

He carried on fitting in a fight here and there, when the RAF permitted it, before was he demobbed at the age of 20.

One of his first fights back on Civvy Street was against former ABA champion Ronnie Bissell at the Liverpool Stadium, which was known as the graveyard of champions.

The Yorkshireman caught him with a good punch to the jaw in the first round and Boland went out like a light and woke up in the dressing room.

After 32 straight wins, the defeat gave his confidence a severe jolt.

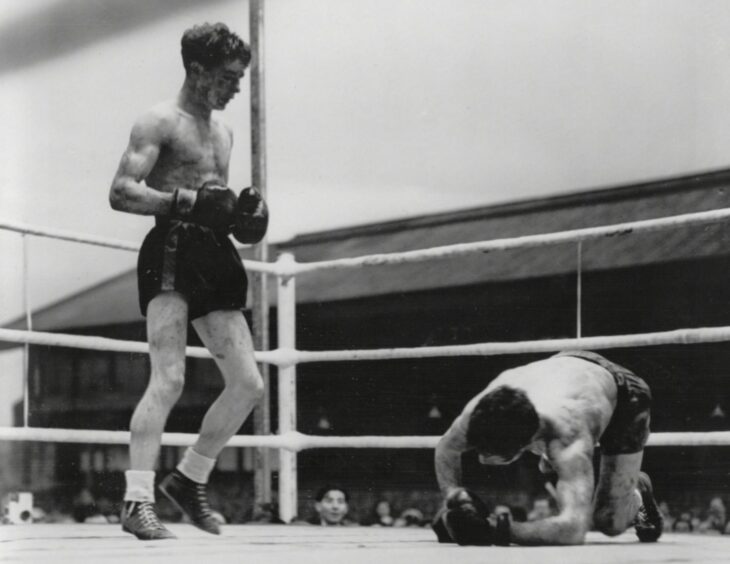

There was revenge later that year at the Kingsway Rink when Boland put Bissell on the canvas eight times before the ref stepped in and stopped the fight.

A non-title bout against Stan Rowan, the reigning British and Empire bantamweight champion, topped the bill at the Liverpool Stadium in October 1949.

Boland stopped him in six rounds but, still only 20, won only the contest, and not the titles, because boxers had to be 21 before they could fight for a belt.

Boland battered in Barcelona

Boland left Dundee for Spain in December 1949.

Air travel wasn’t all that common at the time so he travelled by train with his trainer, Jim Brady, to fight the Spanish boxer Luis Romero in Barcelona.

At the weigh-in before the fight he picked up a boxing magazine that was lying on a table and discovered that Romero was the European champion!

Boland recalled: “Most of his opponents didn’t stay around long enough to hear the final bell.

“At the weigh-in I found a few English-speaking Spaniards who were eager to pass on some more information about Romero.

“They told me not to worry, Spanish hospitals, they said, were really quite efficient.

“And, anyway, the way Romero punched, the fight wouldn’t last all that long.”

Boland stepped into the ring in Barcelona and by the end of the first round he realised Romero punched harder than any man he had ever met in his career.

“Every punch ripped into me and there seemed no escape,” he said.

“At the end of the second round I’d given up all idea of winning the fight and my one aim was to be still alive at the end of it!”

Romero’s punches actually flayed patches of skin off Boland’s body but he survived the 10 rounds and had no complaints when he lost the contest on points.

Ironically, it was the gallant manner in which he lost to Romero that brought the offer of a British title shot against the legendary Peter Keenan for his British and Empire bantamweight titles at Firhill Stadium in Glasgow on June 27 1951.

It was the bloodiest title battle ever seen in Scotland and he lost by 12th round stoppage in a scrap that wouldn’t have looked out of place in one of the Rocky films.

During his action-packed career, he fought two world champions, four European champions, three British champions and champions of France, Spain, Italy, Canada and Cuba.

Boland was fighting Malcolm Ames at the National Sporting Club in Piccadilly in 1956 when the referee accidentally kicked him and snapped his Achilles tendon.

He won the fight on points but had to go into hospital for an operation, which was successful but left him with a limp.

Ring king started new career in wrestling

“From time to time, after that I returned to the boxing booths, mainly at fairgrounds in the south of England,” said Boland.

“Over the years I’d had discussions with my friend, George Kidd, the world lightweight champion, on who would win a bout between a boxer and wrestler.

“We agreed that it would depend on how good each was at his particular sport.

“One day George contacted me and said he had a wrestler who was willing to take on a boxer in a special bout in the Caird Hall.

“The wrestler was an American called Red Callaghan. I agreed to take him on and the fight caught the public imagination.

“On the night, they were standing in the aisles.

“The fight didn’t last long. I knocked out the American in the first round.

“But the bout was a success and soon I had offers flooding in from all over the country for me to take on other wrestlers.

“The bouts were all big draws and I managed to win them all.

“After that I went into straight wrestling.

“Now I know people say wrestling is all faked and no one gets hurt.

“All I can say is that in my year as a professional wrestler I picked up more injuries than I did in 12 years as a boxer.”

After hanging up his boxing gloves, he ran a news agency in the Hawkhill before spending three decades as a taxi driver in the city.

Boland was inducted to the Scottish Boxing Hall of Fame in 1997.

He died in 1999, aged 70.

Life for a boxer in the ’40s and ’50s was as different as chalk and cheese when compared to the extravagant lifestyles of today’s multimillionaires like Anthony Joshua, Tyson Fury and Katie Taylor.

Boland wouldn’t have changed it for the world.

“I’m often asked if I regret having my boxing career when I did,” he said.

“The answer is an emphatic no. I was boxing at a time when the sport was booming all over the country.

“The saddest day of my career was when I finally hung up my gloves.

“I’ve never met an ex-boxer who wouldn’t do it all again if he had the chance. Surely there can be no finer tribute to the sport?”

Conversation