These forgotten images capture life in Whitfield through the decades.

The rediscovered photographs from the DC Thomson archives document a period of seismic change and take us back to the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

Dundee Corporation wanted to tackle slum dwellings after the war and build new housing schemes to tackle overcrowding in a city that was running out of space.

Some were triumphs, others were disasters – many had moments of both.

The city expanded into the suburban development of green fields and the Whitfield estate was built from 1967 to accommodate the rapidly expanding population.

The area was previously farmland.

The name Whitfield relates to the topography of the area, which was probably home to a plant called bog cotton that can create the appearance of “white fields”.

Possibly the earliest mention of the “Whitefield” estate was in The Register of the Great Seal of Scotland in 1510, when Archibald of Douglas was given various lands.

In 1952 a draft plan for the development of Dundee was drawn up by planning consultant Dobson Chapman, which took three years to complete.

Greenfield land in the north of the city was selected for future development, in what would become known as the Whitfield estate.

It was expected that it would finally wipe out Dundee’s housing waiting list.

Outline plans for a Dundee Corporation estate in the Longhaugh-Whitfield-Kellyfield area, comprising 4,500 homes, was approved on May 11 1965.

Budgets were tight, time was short and bricks were scarce so concrete became the material of choice and Crudens Ltd of Musselburgh was awarded the contract.

Crudens was the British agent of the Skarne system from Sweden, which permitted fast construction and reduced costs through the use of pre-fabricated concrete sections.

The original proposals for street names in 1967 included Lilac Mount, Walnut Grove, Cypress Crescent, Primrose Bank, Sorrell Mount, Acacia Avenue and Laburnum Bank.

The multi-storey blocks comprising 360 flats were built in 1969.

There were actually two blocks, making four courts.

These were the 16-storey Quarryfield and Whitfield Courts and the neighbouring tower block which housed Greenfield and Kellyfield Courts.

Seen from above, the Skarne area – which was was completed in 1971 for £8.5m – used to look like a honeycomb, made up of 130 distinctive deck-access maisonette blocks.

Several streets were named after areas of East Lothian where Crudens were based, including Haddington Avenue, Berwick Drive and Dunbar Crescent.

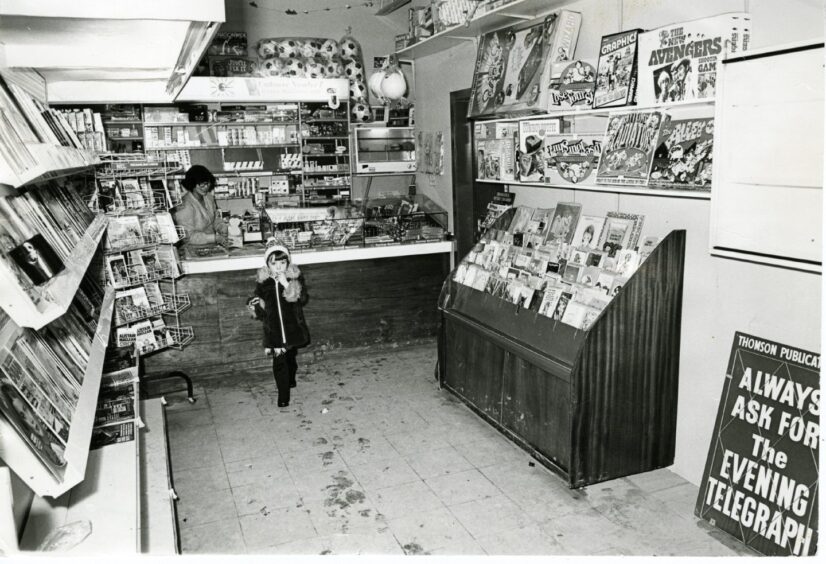

A shopping centre was built, and the Whitfield Bar.

The development was supposed to be the last major part of the solution to Dundee’s slum clearance programme with miles of “walkways in the sky”.

They were initially feted but living conditions rapidly deteriorated.

The south part, off Whitfield Drive, consisting largely of semi-detached dwellings, was popular, but the problem was the Skarne dwellings in the north.

By the mid-1970s it had gone from an architect’s dream to one of the worst in Scotland where law-abiding citizens would not tread at midday, never mind midnight.

Safety catches were installed on 1,583 of the windows in 1977 with grilles added to the raised walkways as the estate started to become a no-go area.

However, many people remember their days in Whitfield as mostly very happy.

Whitfield’s population had fallen well below capacity by the 1980s, its unemployment rate was a staggering five times the already-high Dundee average and almost three out of every four households had an annual income of below £5,000.

One quarter of the available homes – mostly in the unloved Skarne blocks – were empty and were the frequent targets of vandals and fire-raisers.

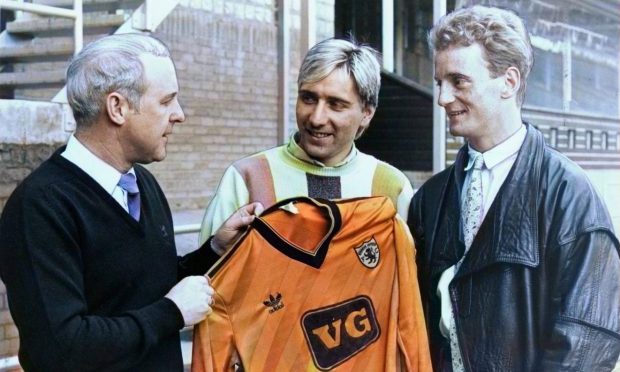

Times were tough but some were determined to chase their dreams.

Some famous ex-residents included Liz McColgan (nee Lynch), who pounded the streets, come rain, snow or frost, on the journey to becoming arguably Scotland’s best-ever distance runner.

Dad Martin and mum Betty helped foster the former St Saviour’s High pupil’s running career and the pair watched on proudly as their daughter captured a world 10,000m title, an Olympic silver medal and Commonwealth gold.

In 1988 the UK Government stepped in, making the estate one of four in Scotland to be singled out for special treatment under the New Life for Urban Scotland project, alongside Castlemilk, Ferguslie Park and Wester Hailes.

The project was being carried out under the direction of Professor Derick McClintock and Peter Young of the Centre of Criminology at Edinburgh University.

Mr Young said: “In the past there have been studies of crime and delinquency among young people but there are other aspects to be considered.

“For example, it could well be that the people who live in Whitfield find things like general noise and kicking footballs about in the street more disruptive than specific acts of crime.

“Most surveys and projects are concerned with hard factual data.

“We are trying to get beneath that to reveal underlying feelings and problems.”

Charles visited the concrete jungle

Significant work was undertaken to give the vast estate a new identity so clearance of unwanted homes — officially known as twilight areas — began in the early 1990s.

The work being done to improve Whitfield started to be recognised at a national level, winning first prize in a community enterprise scheme backed by Prince Charles.

The future king toured parts of Whitfield in October 1989, where he was to praise the efforts made by tenants to improve their living conditions and environment.

He highlighted the ugly Skarne blocks and told residents he understood the nature of the problems faced in Whitfield and said they were inherent with bad design.

Charles saw empty, unmodernised flats in various states of decay as well as newly developed areas such as the prize-winning Dunbar Park.

It was at Dunbar Park that he witnessed how the tenants, local authorities and private sector were combining to give the vast estate a proud new identity.

Since 1990 tenants had been transforming the North Skarne blocks into an attractive development of new houses designed by tenants themselves.

A milestone moment arrived in 1995 with the announcement that the Scottish Office was withdrawing from the Whitfield Partnership, three years earlier than expected.

Charles made sure he was kept up to date with progress and when he made a two-day visit to the city in June 1995 the housing scheme was his first port of call.

Negative perceptions of Whitfield estate a thing of the past

Things in Whitfield took another step forward in 1996 with the completion of a £10 million programme to build houses on the site of some of the old Skarne blocks.

Whitfield’s multi-storey blocks somehow survived being demolished.

As disillusioned families moved out for more traditional accommodation, the half-empty blocks attracted drug abusers and vandals, making life a misery for the remaining high-rise dwellers.

But time was running out.

A council working group, comprising councillors, tenants representatives and council officers, was set up to identify and report on housing which was potentially at risk.

Quarryfield and Whitfield Courts would be the first to be demolished on May 25 2003 and the neighbouring Greenfield and Kellyfield Courts would follow in April 2004.

Since 2006, scores of council houses have been demolished and replaced with hundreds of new homes.

The core of the estate has been reborn.

Only 3,998 people still lived there in 2006 but completed regeneration projects are starting to have a positive impact and more are moving back to Whitfield.

This is a story of survival against the odds.

Conversation