President John F Kennedy loved the sea.

He had a keen interest in old ships and had several models in the White House.

The week he was assassinated in Dallas he was meant to be sent a 30-minute colour film of the moving of the Unicorn at Dundee harbour.

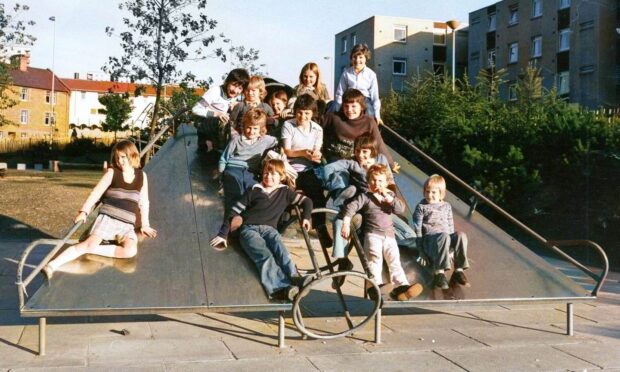

The journey to save the 46-gun frigate drew the biggest crowd Dundee harbour had seen since the foundation stone of Earl Grey Dock was laid in 1832.

It was a movie the president was looking forward to seeing.

He never did.

It was a sliding doors moment with a sadder ending.

His all-too-brief presidency ended before he had the chance to live up to the high hopes America, and the world, had for him.

Unicorn was almost broken up and sunk

HMS Unicorn launched in 1824 and spent her early years in reserve – or ‘ordinary’ – in the south of England before she was brought to Dundee in 1873 to serve as the reserve training ship for the Tay.

She lived in Dundee without a great deal of fuss being made about her until 1962, when she was in the way of one of the approach roads for the new Tay Road Bridge.

Earl Grey Dock, where the 46-gun frigate was moored, was due to be filled in and it was decided the old lady should be broken up where she lay.

The frigate was eventually given a reprieve from Lord Carrington, First Lord of the Admiralty, after a deputation from Dundee went to London to argue the case and the Queen Mother joined calls to save the ship.

Agreement was reached that an attempt would be made to move her but if she started to break up during the tow she would be taken to deeper water and sunk.

In an intricate operation over October 12 and 13, the Unicorn was first hauled off the bank of mud it lay on at Earl Grey Dock, then escorted out on to the river by two tugs.

The black and white frigate once again felt the ripple of water past her sides as she gracefully moved down river and 20,000 people turned out along the harbour.

Arnold Millar from Saggar Street was among those watching the historic journey.

The 34-year-old recorded all the drama and excitement on his cine camera as the oldest ship of the Royal Navy still afloat put out into the Tay for the first time in 90 years.

Mr Millar had a bird’s eye view and his first feature-length production was seen by the Royal Navy, the New Zealand Navy, the US Navy and the Russian Navy.

Prince Philip had seen it and the Queen knew of its progress.

Mr Millar knew all about President Kennedy’s love of the sea and wrote to the White House to ask if he would be interested in viewing the historic cruise down the Tay.

He was.

Kennedy asked for it to be sent on to the White House.

Naval Aide to the president, Captain Tazewell T. Shepard Jr, wrote to Mr Millar about the delivery and said he would “ensure the film’s prompt return afterwards”.

Kennedy’s love for maritime materials was well-known and visiting heads of state would often present him with priceless additions to his collections.

Young John might still be too young to understand the full significance of the film, but I think Mrs Kennedy will appreciate the gesture.”

Arnold Millar

But tragedy struck before the parcel was conveyed to the White House.

The president had been nearing the end of a two-day tour of Texas when he was shot on November 22 1963 while riding through the streets of downtown Dallas.

At the now-notorious Deeley Plaza, bullets fired by a sad loner, Lee Harvey Oswald, hit him in the head and he died almost instantly.

The historic images of that horrific day were captured by snapshots and home movie camera footage taken by people in the crowd.

Later came clearer, but just as compelling, pictures of the aftermath.

His wife, Jackie, standing in her bloodstained coat beside Lyndon Johnson as he took the presidential oath on Air Force One.

And Oswald being shot by Jack Ruby at Dallas Police HQ while cops in white Stetsons gaped in disbelief.

What happened to the Dundee Unicorn movie JFK wanted to see?

The White House received a flood of condolence messages.

Dundee Lord Provost Maurice McManus was among them and he conveyed the city’s “deep sense of shock at the terrible tragedy which had befallen the American people”.

One letter writer to the Evening Telegraph suggested naming the new inner ring road in Dundee in honour of the great statesman.

The pipes and drums of The Black Watch were the only non-American service personnel to join the funeral procession in Washington on November 25 1963.

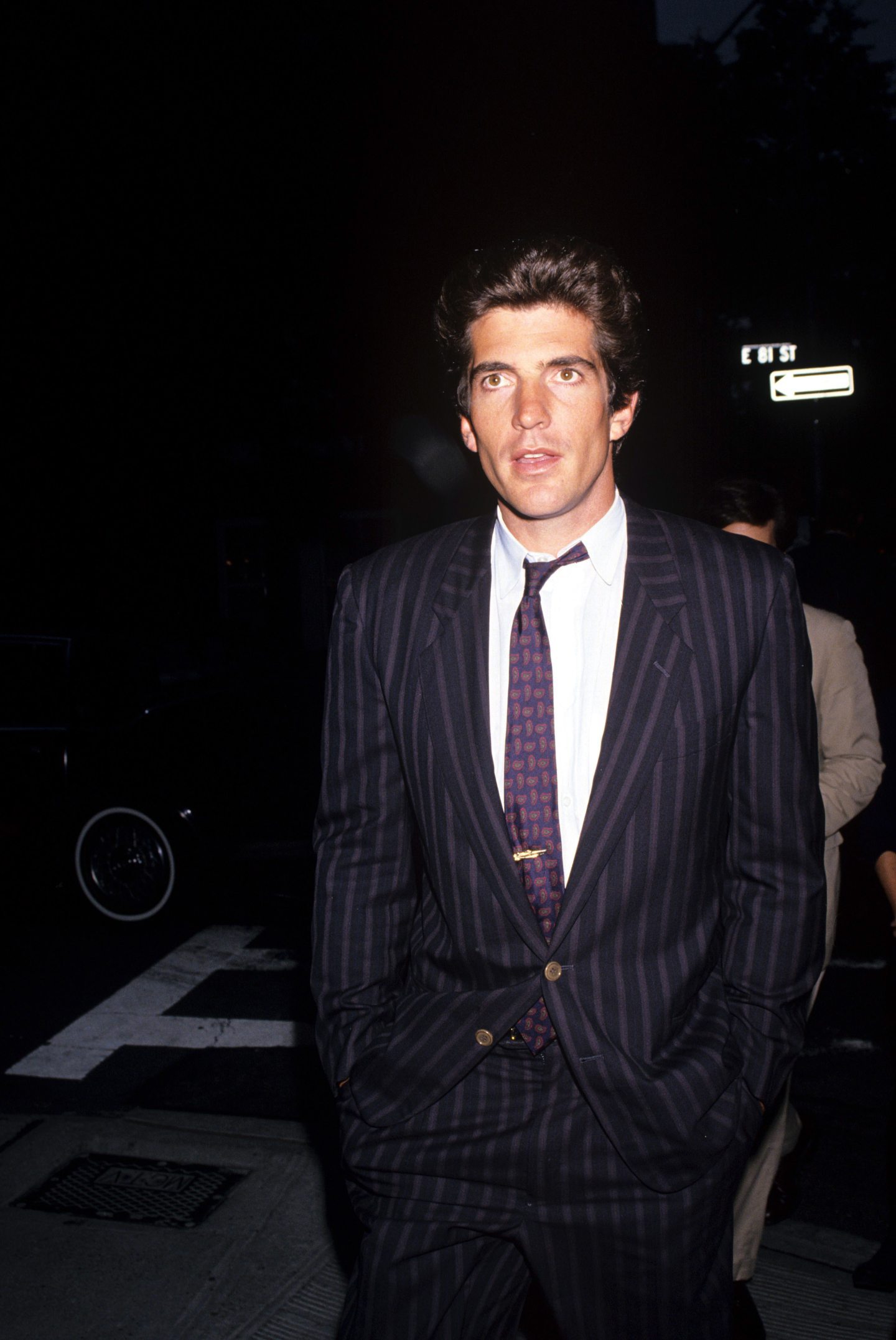

Millions of people around the world watched Kennedy’s three-year-old son, John, also destined to die tragically, saluting his father’s coffin, too young to know who was in it.

The child’s last goodbye to his father touched the American nation.

And those closer to home.

Mr Millar watched and wept and decided he would send the 30-minute “Operation Unicorn” to John as a mark of respect to his father’s memory.

Mr Millar said: “Young John might still be too young to understand the full significance of the film, but I think Mrs Kennedy will appreciate the gesture.

“It is my personal tribute to a great man.”

The film was greatly appreciated by Mrs Kennedy.

Mr Millar — who died in 1993 — would treasure the letter of thanks he received.

John Jr grew up to have a love of the sea, like his father.

He became a lawyer, journalist and magazine publisher before his own life was cut tragically short in a plane crash in 1999.

He was just 38.

In a private ceremony aboard the destroyer USS Briscoe, his ashes were returned to waters off the Massachusetts coast where he enjoyed sailing and sea kayaking.

We will never know whether John Jr watched Operation Unicorn.

‘Back from whence we came…’

At a 1962 Newport dinner for the America’s Cup crews, John F Kennedy attempted to explain his love of the sea.

“I really don’t know why it is that all of us are so committed to the sea, except I think it’s because in addition to the fact that the sea changes, and the light changes, and ships change, it’s because we all came from the sea.

“And it is an interesting biological fact that all of us have in our veins the exact same percentage of salt in our blood that exists in the ocean, and, therefore, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears.

“We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea – whether it is to sail or to watch it – we are going back from whence we came.”

Conversation