The grim discovery of the body of Harry Falconer was made by electricians rewiring his council home in Dundee 50 years ago.

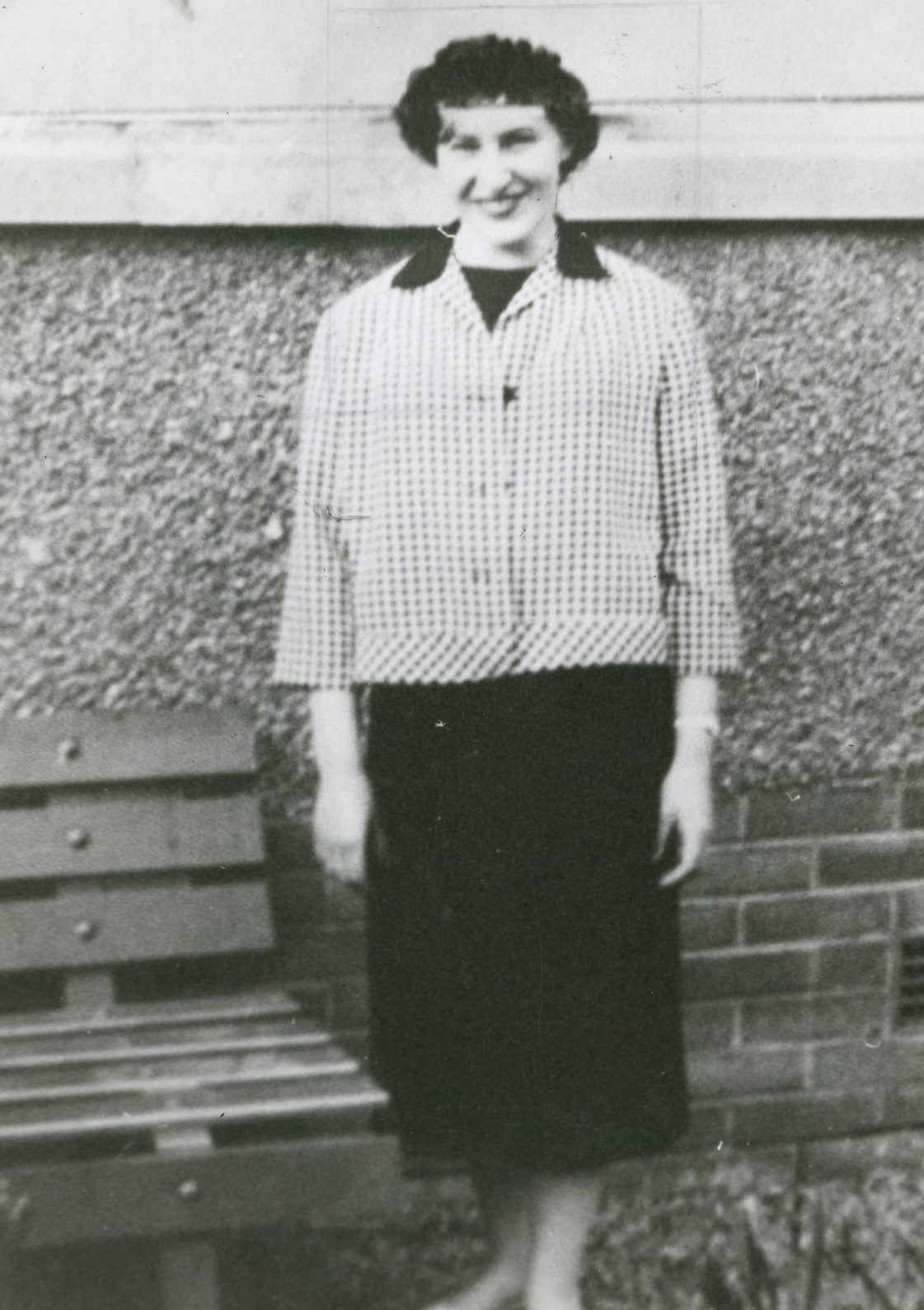

Police swooped on the three-bedroom council house in Macalpine Road, St Mary’s, and later charged his wife Isabella with his murder.

She was said to have dragged his unconscious body to a hatch in the kitchen floorboards and dropped him in after he had fallen into a drug and drink-fuelled stupor.

It was further alleged that she then deprived him of food and drink and covered over the hatch with linoleum, carpet and furniture.

The self-employed salesman was last seen between Christmas and Hogmanay in 1972.

The 38-year-old father-of-four was still dressed in a shirt, braces, belt, trousers and socks when he was found seven feet below the kitchen floor.

The carpet covering the hatchway was where the dog’s dish was kept.

It became known as the “body-under-the-floor murder trial”.

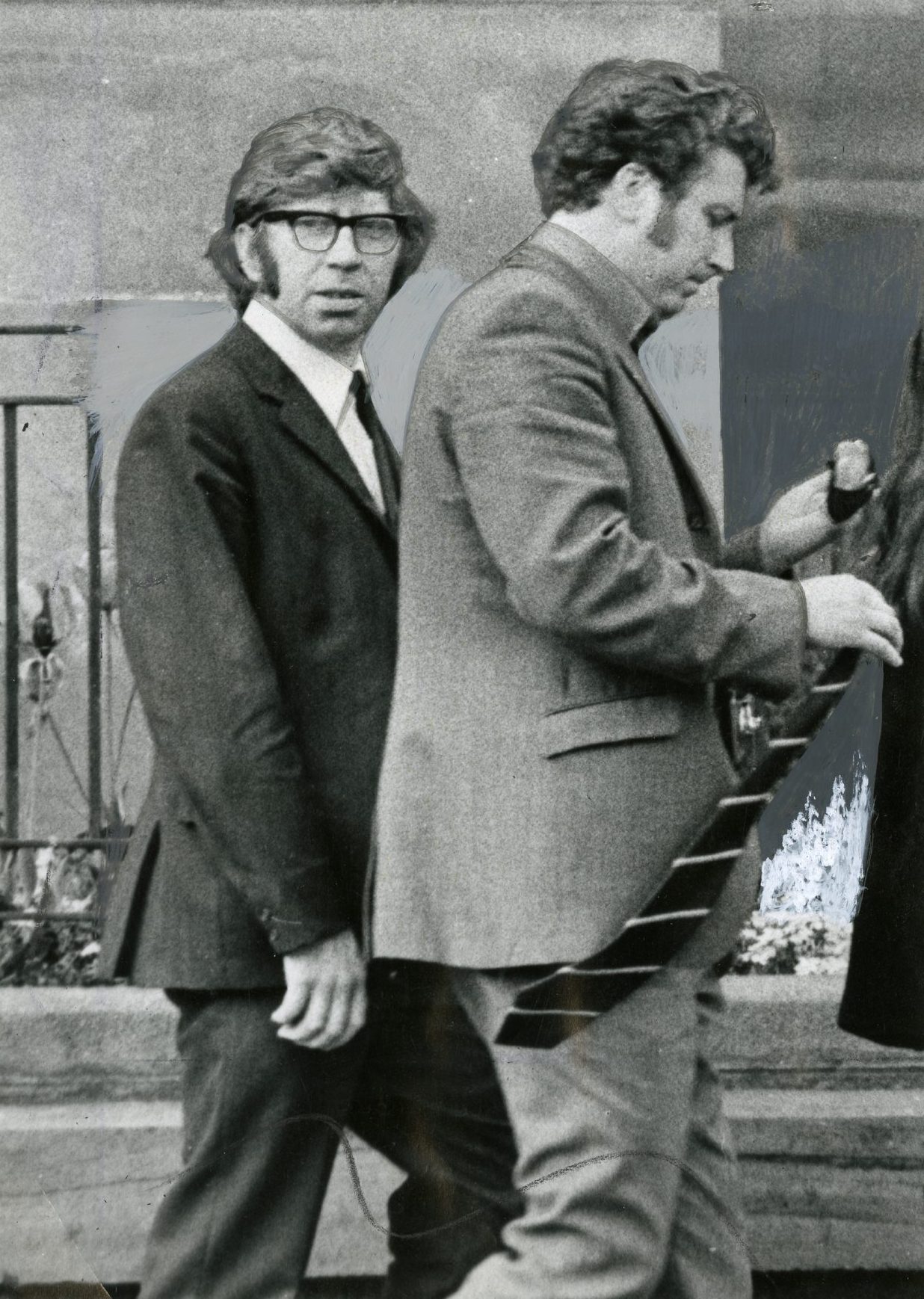

Mrs Falconer, who was 37, denied the charges when the trial started at Dundee High Court in May 1974 before a jury of eight men and seven women.

Dundee Public Works Department electricians Albert Fraser and Maxwell Patterson described completing rewiring upstairs on January 29 1974 before taking a lunch break.

Mr Fraser said he was just at the stage where it was necessary to gain access to the foundations of the house when Mrs Falconer said she was going to go out to the shops.

He described how he lowered an inspection lamp through a hatch down into the foundations of the house and illuminated the body of a man lying there.

“At first I thought it might be a dummy,” he said.

“Then I saw feet, then I was sure it was a body.”

They raised the alarm with the police.

PC James Marshall said Mrs Falconer came back and he told her the house had been seized by the police because they had discovered what they thought was a body.

“She did not appear to be upset in any way,” said PC Marshall.

Subsequent witnesses — many of them relatives — described Mr Falconer as a “chronic alcoholic” who took barbiturates and suffered from hallucinations.

Joyce Falconer, the 12-year-old daughter of the deceased, wept unconsolably as she spoke of the last time she remembered seeing her father before Christmas 1972.

Her father was “drunk nearly all the time”.

She said: “He used to take Mandrax tablets when he was drunk.

“They made him worse and he imagined all sorts of things, such as gold padlocks on the door and snakes crawling all over him.

“He sometimes collapsed on the floor and my mother would try and lift him to a chair or put him to bed — she did that lots of times.”

On occasions he would hit her mother and herself.

Sarah Devlin, 46, the sister of Mr Falconer, said her brother developed a drink problem by the time he was 15 or 16 after his mother died when he was just eight.

Mr Falconer had significant spells in hospital for alcoholism and drug addiction.

He discharged himself more than once against medical advice.

Body of Harry Falconer was in a state of mummification

Significant witnesses were Dr Donald Rushton, the police surgeon, Dr Alexander Murray, the Falconers’ family doctor, and, John Durie, the “cruelty” inspector.

Dr Rushton said he thought Falconer was probably alive when dumped.

He thought he could have survived for up to 10 days but it was more likely to have been a few hours.

Dr Rushton said advanced decomposition had prevented identification by ordinary means and determining the cause of death, which was given as “unknown”.

There was heavy infestation by small black flies and maggot cases.

The hands were extensively decomposed and skeletonised.

The back of the trunk and the limbs were in a state of mummification.

He said there could be little doubt the deceased was seriously intoxicated by drugs near the time of death and this would be especially so if alcohol had also been taken.

Dr Murray said Mr Falconer was a hopeless alcoholic who had a death wish.

He described this as a “desire for immediate oblivion”.

Taking drink and drugs as Mr Falconer did was a repeating process “until death caught up with you” and he “couldn’t care less whether he lived or died”.

He said Mrs Falconer’s whole life was “putting up with trouble” and he didn’t think she was “emotionally capable” of putting him down the hatch and leaving him there.

Mr Durie was a senior inspector with the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and had been officially involved with the Falconer family since 1964.

He said Mrs Falconer admitted to him that she had dumped the body down the hatch but didn’t know if her husband was dead or alive when he took the drop.

But there was a further shock to come.

The prosecution decided to withdraw the indictment.

A strange and mysterious affair

Advocate depute Donald Macaulay said the case against Mrs Falconer could not be corroborated with the evidence available to prove that she was guilty.

Lord Stott, addressing the jury, said: “In a situation such as this, there could be no means of knowing, for any of us, whether the man was dead or alive when he came into the hatch, and you can only murder a living person, not a dead one.”

The judge ordered the jury to find Mrs Falconer not guilty.

Before leaving the bench he described it as “a strange and mysterious matter”.

Mrs Falconer fled swiftly out of a side exit and sped off in a waiting car.

She was in tears.

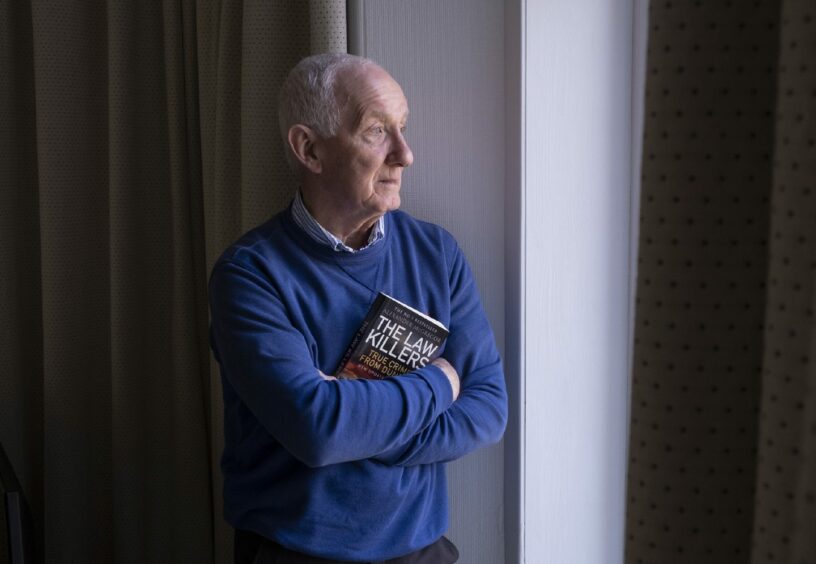

Alexander McGregor, former Courier chief reporter and author of The Law Killers, covered the trial in May 1974 and says it was unique among murder trials he attended.

“The prosecution case built up considerable sympathy for the accused and none for the victim, which was extremely unusual,” he said.

“All the evidence pointed to the miserable life Mrs Falconer had been forced to endure.

“Witnesses told how, in addition to his habitual drunkenness, she had regularly been physically and mentally abused.

“She was also frequently humiliated.

“I’m pretty sure that if the case had ever got the length of the jury, they would have acquitted her.

“But the jury having to decide always seemed unlikely.

“There was virtually no evidence that her husband was alive when he was put under the floorboards and it was never suggested that Mrs Falconer had killed him beforehand.

“It always seemed to me that the Crown had felt obliged to take the case to court, but having presented all the circumstances, and particularly about the life she had led, justice was served by ending the trial when they did.”

Police Scotland said the case has never been closed.

Conversation