Mining was the lifeblood of Fife.

The region became one of the cornerstones of the Scottish coal mining industry, which at its peak employed 150,000 men in 500 pits across the country.

A dirty and dangerous job it might have been, but the money was fairly decent, if hard-earned, and the local area depended heavily on the pitmen’s pounds and pennies.

Virtually everyone in the area was related to someone who worked in the pits at some time or another and the roll call of collieries reads like a map of Fife.

Communities sprang up around the pits, including the creation of new towns such as Glenrothes in 1953, which was largely built for workers of a new coal mine.

However, the death knell began sounding in the 1960s and 1970s, and what little remained of the once proud industry was reduced to a rump by the time the miners’ strike came along in March 1984.

MacGregor was known as Mac the Knife

Ian MacGregor, head of the National Coal Board, had announced plans to close 20 coal mines which were designated uneconomical, resulting in a loss of 20,000 jobs.

MacGregor believed that much of British industry was hopelessly uncompetitive and was of the opinion that mines whose costs were too high would have to close.

MacGregor had been personally appointed by prime minister Margaret Thatcher and it was announced that Cortonwood Colliery in Yorkshire would be the first pit to close.

The mine’s 9,000 miners downed tools immediately, and just four days later all South Yorkshire miners had joined them on the picket line.

When the coal board announced that another five pits were to be closed in just over a month, Arthur Scargill, the leader of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), called for a national strike on March 12.

Workers at the Frances Colliery at Dysart and the Seafield on Kirkcaldy’s waterfront were among the first in the country to walk out in 1984, with many of the workforce actually going on strike on February 10 as the coal board were sending men home due to a breakdown on one of the belt drives.

Soon, half of the UK’s 187,000 miners had joined the action.

You forged a lot of friendships and there were a lot of good people in the mines.”

Former miner Jim Anderson

The miners had gone on strike twice in the previous decade over wages, which brought blackouts, meals by candlelight and the introduction of a three-day working week.

Most believed the 1984 strike would be over quickly, but as the dispute dragged on through the summer the financial penalties for striking miners began to hit home.

Used to being the best-paid manual labourers in the country, many had to rely on food parcels and soup kitchens to make it through the winter.

Bogside pit was earmarked to close

Jim Anderson from Cardenden was among those to walk out in the miners’ strike of 1984.

He worked at the Bogside Colliery, which was part of a group of three pits which fed their coal by underground conveyor belt to the Longannet Power Station.

“I left school at 16 and joined the National Coal Board in 1968 to serve my apprenticeship as an electrician,” he said.

“Everyone knew someone who worked down the mines.

“You forged a lot of friendships and there were a lot of good people in the mines.

“It was a dirty job but you got your shower at the end of your shift.

“Everybody stuck together.

“Like every working relationship, you could have your arguments because nobody held back, but at the end of the shift you would go and have a pint together.”

Bogside was being closed by the NCB following flood damage, which Jim described as “industrial sabotage” during a strike over disciplinary action in February 1984.

“We were very angry,” he said.

“Myself and some colleagues volunteered to go underground and restore the power and get the pumps working to try to save the mine and management blocked us.

“They simply wanted to close the mines.”

Soup kitchen a lifeline during 1984 miners’ strike

He said Thatcher’s policies on coal mining were a politically motivated attempt to destroy the power of the trade unions and crush the industrial working classes.

“Every mine in Scotland was at threat of closure under Thatcher,” said Jim.

“At the time I was living in Dunfermline and married with a young son.

“I had a young family to think about so going on strike was a very big decision.

“It was hard, let me tell you, because when we walked out we got absolutely nothing.”

The strike, considered to be one of the most bitter ever, lasted just under a year.

Clashes between police and strikers were regular occurrences during the dispute, as were increasingly bitter and bloody battles between striking miners, and those who continued to work down the pits, much to the anger of their former colleagues.

Jim’s savings account had to be used for paying bills.

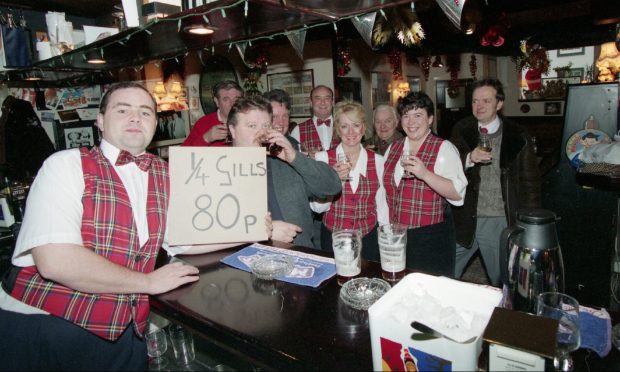

“But there were a few times I had to take my young son to the soup kitchen which was set up at the local miners’ welfare club,” he said.

“He thought it was a big adventure getting his lunch with all these men.

“The children didn’t understand what was going on.

“That was tough.”

Communities were divided across Fife

Ten strike centres were set up in Fife, and Gordon Brown, then a fresh-faced MP, was made an honorary life member of the NUM for the support he gave picketers.

Communities were divided over the action, with those who chose to return to work branded “scabs” while haulage drivers who transported coal were pelted with missiles.

“You don’t cross a picket line when people are fighting for their lives,” said Jim.

“The strike seemed to last forever, but we had to fight for our rights.

“There was no going back.”

Finally, on March 3, nearly a full year after the strikes began, NUM delegates at a special conference voted by 98 to 91 to call off the strike.

Bogside finally closed in 1986 and Jim took up employment with a soft drinks manufacturer, but he remains angry about the way the miners were treated.

“The coal industry could have continued if it had been handled differently,” he said.

“It didn’t need to end at that time.”

The Frances colliery closed during the strike when fire broke out deep underground and destroyed its only working coal face.

Seafield managed to survive for a few more years but the writing was on the wall when it too was hit by blazes deep underground.

How long did 1984 miners’ strike last?

Alan Moyes was among those who walked out at Seafield in 1984.

The former Beath High School pupil served his apprenticeship with the NCB as a mechanical fitter and worked at Valleyfield at Newmills from 1973 to 1978.

He moved to Seafield from Bogside just before the 1984 miners’ strike.

It was a baptism of fire.

“We were safe at that point but we could have been next in the firing line,” he said.

“It was a show of solidarity.

“I was worried about money because I’d been married for three years by then and we had just bought a house about nine months before that.

“We were lucky that my wife was also working and we had help from family and friends.

“Did I think the strike would last a year?

“You were hoping it wouldn’t, but the government was digging its heels in and it was also the hottest summer in a long time so people weren’t using coal.

“I saw it through to the end.

“It was tough, and every day you got up you were hoping for news that we were going back to work, but it went on and on.”

Alan is now 67 and retired, but when Seafield closed in 1988 he went back to college after deciding on a career change and landed a job in IT.

Henry McLeish, who was leader of Fife Regional Council during the miners’ strike, described 1984-85 as one of the worst years of his working life.

“There were enormous hardships in Fife, which really had the biggest coal community in Scotland,” he said.

“One of the most shocking aspects of it was we literally saw families collapse because of the pressures of the strikes.

“We’re talking about serious financial, emotional and social hardships.

“Families did break down and did break up because the pressures were enormous.

“At the same time, there was the absolute solidarity of the mine workers for a cause that was going nowhere.”

Alongside the council’s convener, Bert Gough, Mr McLeish helped mining families access a range of support – from financial assistance to wood to heat their homes.

Women in coalfield communities

Women’s voices are largely absent from accounts of the miners’ strike, although a book co-authored by Dr Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite and Dr Natalie Thomlinson sought to change that.

Women and the Miners’ Strike 1984-1985 contains oral histories featuring 100 women.

Dr Thomlinson and Dr Sutcliffe-Braithwaite said most of their interviewees “assumed that this would be another short strike; annoying, perhaps, but not life-changing”.

Some presented the strike as a “moment of liberation”, including Alice Samuel.

She and her husband, a miner, and their young family moved to Fife just a few weeks before the start of the strike in 1984.

For her, getting involved in her local strike centre was a way of getting involved in the community as a whole, “and breaking out of the isolated position she was in as a newcomer in Fife”.

In High Valleyfield, Alison Anderson, who was solidly behind the strike, recalled in the book how there were “loads of times” she wished her husband was working.

“But you knew you couldn’t – you knew you could never live in that community – that would have changed your life,” she said.

It was only when her husband was made redundant when his pit closed after the strike that the redundancy money finally allowed them to pay off their remaining debts.

Was it all worth it?

Although the miners went back to work after the strike, almost all the remaining pits they’d been fighting for closed down one by one in the years that followed.

Graffiti daubed on a Kirkcaldy wall shortly after the end of strike in 1985 summed up the feelings of many.

In large white letters, it asked: “A year wasted – for whit?”

Conversation