History is being made in Perth as the long awaited £27 million Perth Museum opens and the Stone of Destiny goes on public display having returned home to Perthshire for the first time in more than 700 years.

The stone was taken from Scone by King Edward I of England in 1296 and placed in Westminster Abbey.

Since then, it has been used in the coronation ceremonies of English and then British monarchs.

In 1996, the stone was returned to Scotland and housed in Edinburgh Castle.

It returned to Perthshire a few weeks ago to form the centrepiece of the new Perth Museum.

But is it possible this is not the ‘original’ Stone of Destiny at all?

Is it possible that in 1296 the English took the wrong one?

Much debate about origins of the Stone of Destiny now displayed in Perth

One famous story linked to the authenticity of the stone relates to Christmas Day 1950.

The ‘Westminster Stone’ as it became known was “liberated” from Westminster Abbey and briefly returned to Scotland by four Scottish nationalist students.

It remained hidden until April 1951, when a stone was symbolically left in Arbroath Abbey.

Speculation – later disputed – ensued that this stone was not the one taken from the abbey, but merely a copy. Others claimed the ‘real’ Stone of Destiny taken by the students had been hidden in St Columba’s Church in Dundee.

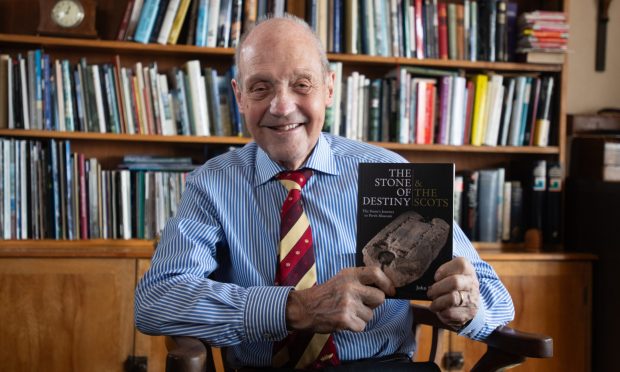

However, it’s another 700-year conundrum that lies at the heart of a new book The Stone of Destiny and the Scots, written by former Perth provost Dr John Hulbert.

While the chronicles – or myths depending on who you speak to – say that the original stone originated in Ireland or Galicia in Spain, he says it’s been proved indisputably that the stone in use at Westminster for more than 700 years is a block of sandstone from Kincarrathie near Scone.

Why are Dr Hulbert’s claims controversial?

Dr Hulbert says his book is controversial because it contradicts most of the academics who have written about the stone, including several from Historic Environment Scotland.

Some believe that the stone now moved to Perth was an ancient Pictish stone requisitioned by King Kenneth MacAlpin after he had subjugated the Picts in 843 AD.

It is said that MacAlpin discarded an ancient Irish Stone, which had been used by generations of the Scots in Argyll, in order to ingratiate himself with the Pictish hierarchy and ease their transition to the Gaelic culture of the victors.

However, Dr Hulbert says the arguments to support this position are “very thin”.

Firstly, he doubts that a conquering army of Scots would have discarded their own ancient “Irish” coronation stone, taking over the royal stone of the defeated Picts instead.

Secondly, if what we now call the Stone of Destiny is the crowning stone that had been used for centuries, originally by the Picts, why was it such a rough, mutilated block of sandstone when evidence from places like Meigle and St Andrews suggests the Picts were master-craftsmen?

What does Dr Hulbert think is the ‘true’ story of the Stone of Destiny?

Dr Hulbert thinks the most likely “true story” is that the “original” Stone of Destiny – reportedly brought to Scone by Kenneth MacAlpin in 850AD – was still in use at Scone when John Balliol was crowned in 1292.

However, when word reached Scone in 1296 that soldiers were coming for the stone, the theory is the Scone Abbey monks found a substitute stone lying in a nearby quarry and gave this to them instead.

It was only when the stone reached London a year later that Edward I realised it was a fake.

This could explain why in 1298, Edward ordered a posse of English soldiers to return and ransack Scone Abbey, possibly because they were looking for the “real” stone.

“The trouble is there’s no concrete evidence for either case,” said Dr Hulbert, 85, who lives in Longforgan.

“But the fact is the only contemporary description of the stone was by a cleric from England called Walter of Guisborough who was probably present at the coronation of King John Balliol at Scone in 1292.

“It’s extremely brief, but he refers to a stone of exceedingly great size. What we call the Stone of Destiny could hardly be said to be that.

“The other thing is the kings of Scotland had royal seals. We have copies of the seals for eight of the kings from Edgar in 1097 to John Balliol in 1292.

“All of them depict a throne which is pretty similar. But the fact is the stone we have in Perth now would not fit one of these thrones.”

Of course, if this is true, it begs the question: what happened to the original “Irish” stone?

Various possibilities are addressed by Dr Hulbert in his book

One theory is it was floated down the Tay to Moncreiffe Hill, south of Perth, hidden and lost.

Another story is that it was hidden at Dunsinane Hill in the Sidlaws.

This was given some credibility when a letter to the Times on January 1, 1819, told the story of two farm workers who stumbled across a chamber at Dunsinane after the ground gave way and they found a large “meteoric or semi-metallic” stone there.

Speculation was further fuelled by historical fiction writer Nigel Tranter when he told how on his death bed, King Robert Bruce gave the “real” stone to the clan MacDonald chief who hid it on Islay to “keep it safe from the English” before later hiding it behind a waterfall on Skye.

“My own feeling for what it’s worth – and I’ve nothing sound to go on,” said Dr Hulbert, “is that it’s probably buried or concealed somewhere in the Scone Palace area.

“The abbey was more or less demolished at the Reformation and many of the stones in the abbey were used to build Scone Palace.

“It’s possible that the real Stone of Destiny was used amongst the foundations of Scone Palace – but we’ll never find that out!”

Whatever the truth, Dr Hulbert says the Stone of Destiny now in Perth, “should be given the prominence it deserves”. Having been used for more than 700 years, it’s a Scottish icon that “embodies Scotland’s nationality in certain ways”.

But preferring to call it “Scotland’s successor Stone of Destiny, he added: “We should not neglect doubts about its origin.”

What’s the view of Historic Environment Scotland about the Stone of Destiny?

Historic Environment Scotland (HES) told The Courier that strictly speaking, the earliest contemporary record of the stone dates to 1297 when it is listed in an inventory of jewels belonging to the former king of Scotland (John Balliol), then in the possession of the English in Edinburgh Castle.

There are no accounts of Scottish king-making at Scone which can be considered to be derived at first hand from eye-witnesses prior to the description of the inauguration of King John in 1292.

Much later stories of the crowning of early kings on the Stone at Scone contained in the 16th-century history by Hector Boece and derivative works are considered to be myths.

However, the attention given to the stone by medieval writers indicates that even in the medieval period the stone was closely allied with the idea of an independent Scottish kingdom of considerable longevity.

A spokesperson for Historic Environment Scotland said: “The earliest origins of the Stone of Destiny have been subject to much debate.

“While the earliest use of the stone and exactly how and when it became associated with king-making remains unknown, legends around its origin strongly link it with kingship and the emergence of Scotland as a nation.

“The fact that no authentic stone has ever been revealed to support alternative theories, along with the tool marks and wear marks that suggest a long history, the strongest evidence is that this is the same stone.”

Conversation