Words, and sometimes their absence, were prominent in the history of Dundee venue The Kinnaird.

Charles Dickens was there to read from A Christmas Carol, while Winston Churchill spoke often from its platform.

It was built as the Corn Exchange on ground presented by Lord Kinnaird.

Dickens had given readings before the formal opening on November 11 1858 during his first for-profit tour, which sold out everywhere – except Dundee.

It was named the Kinnaird Hall in 1865.

From then on it was Dundee’s principal venue for concerts and political meetings.

Past prime ministers William Gladstone, Herbert Henry Asquith and David Lloyd George all received the freedom of Dundee there.

For many years at the end of the 19th Century and beginning of the 20th, Hamilton’s Excursions paid annual visits to the hall.

They were remembered most for the Diorama, a forerunner of films consisting of a series of pictures painted on rolls of canvas.

Roller skating rose, boomed and declined

The hall became a popular rink in the early 1900s, as Dundee residents were taken up in the whirl of the roller skating boom.

The Kinnaird was decorated with Union flags, bunting and Chinese lanterns.

In the meantime, the Hamilton family had taken firm roots in Dundee.

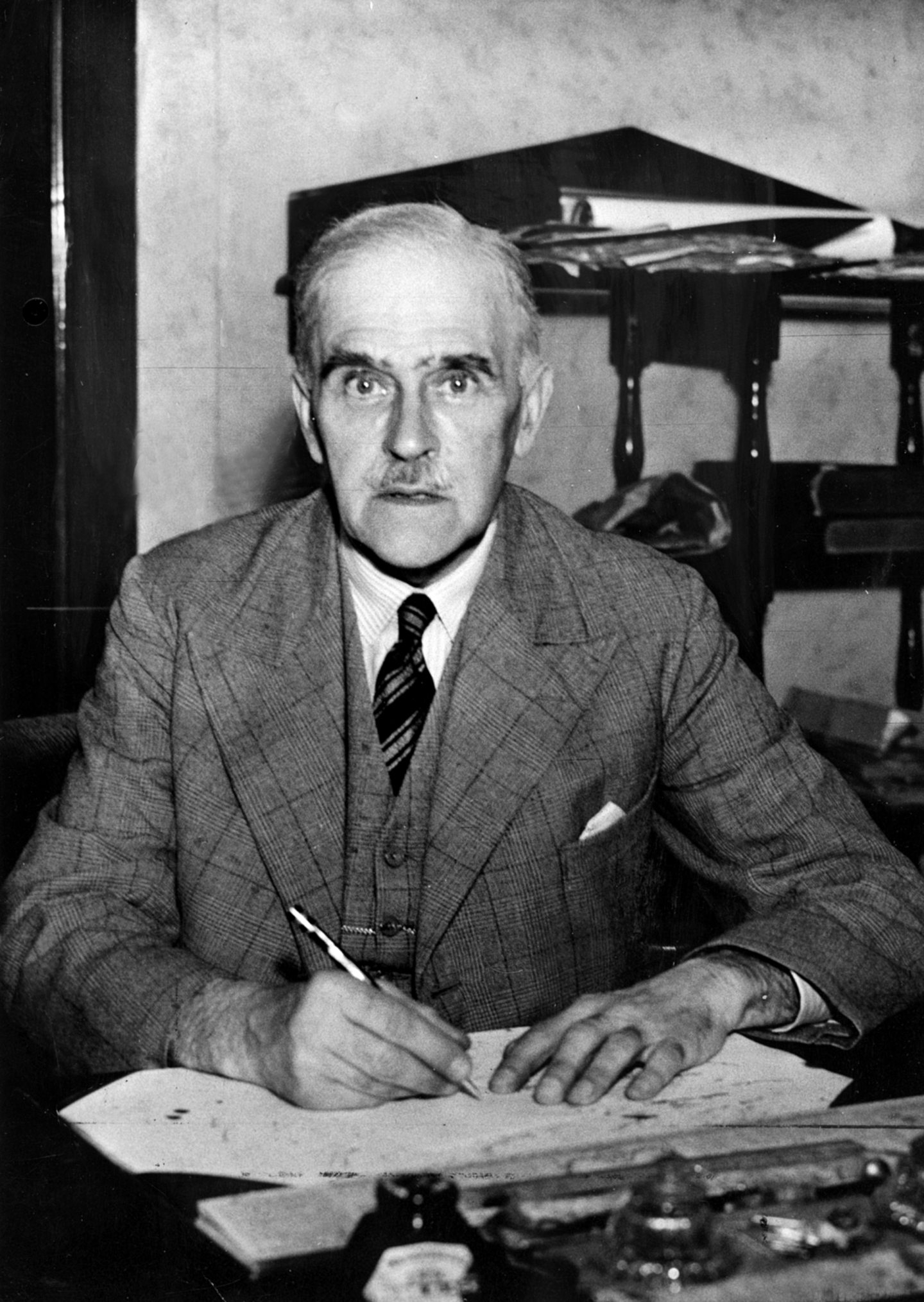

Victor Hamilton caused something approaching consternation when he secured a lease of the Kinnaird Hall in 1919 and launched into the cinema trade.

Thousands of pounds were spent altering the building.

He installed two Gaumont projectors in their concrete operating boxes and there was capacity for 1,268 seats and 74 standing.

An orchestra of 12 was booked to provide the music.

The happy cries of skaters were replaced by the thrilled hush of the audience when the Kinnaird became a cinema.

The opening night in 1919 was a great occasion.

The films Little Miss Hoover and Daughter of the West were shown.

There was also a Gaumont Graphic newsreel and “vocal interludes” by Alice McLauchlan from Edinburgh.

A bidding war for the Kinnaird

Dundee fell in love with the movies as the stars of the silent film era cast their spell.

His first year was so successful that Hamilton offered to buy the Kinnaird outright.

But the directors of the owning company decided they would get as much for it as they could and put the building up for auction in April 1920.

The minimum price was fixed at £15,000 and was immediately offered by Albert Ernest Pickard, the famous Glasgow cinema proprietor.

After that it mounted rapidly by £50 bids.

Mr Pickard made his final offer at £21,200.

Mr Hamilton raised the bid by £100 to £21,300, which was the highest.

The Kinnaird was packed out night after night in days when an audience became carried away with the stories as they unfolded on the screen.

There was something magical about the silent movies.

They transported people into mesmerising worlds of intrigue and romance, adventure and fantasy.

Gimmicks were designed to pack seats

George Caine of The Kinnaird had a flair for advertising.

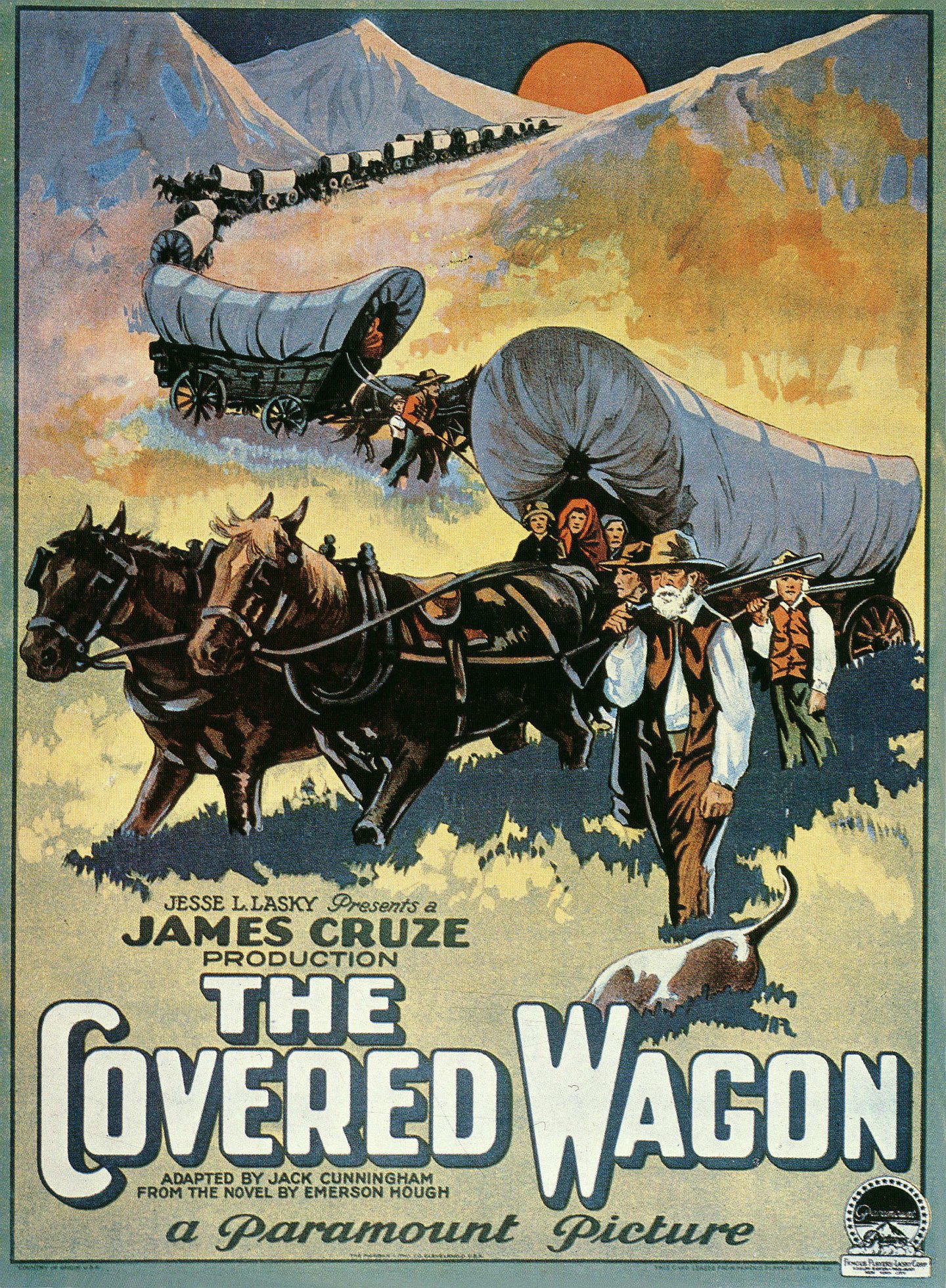

He really went about it in style with the big-scale pioneer western, The Covered Wagon, from 1923, which was an enormous box-office success.

He kitted out a few people in cowboy gear and big hats and then drove them around the streets in a mock-up of a covered wagon, throwing out bills for the film.

By the end of the 1920s the talkies had arrived and words were centre stage at the Kinnaird once more.

Mr Hamilton installed the heavy equipment and interior alterations needed in the rush to exploit the new talking pictures.

He also increased capacity to 1,476 seats.

The Kinnaird audiences first heard their heroes speak when The Cohens and Kellys in Atlantic City was shown in July 1929.

It was just a shame they couldn’t understand what was being said.

The Courier said the dialogue was “difficult to follow” for the audience due to the “very pronounced American accent of all the characters”.

In spite of this, the film was well received.

Victor Hamilton predicted the colour era for film

Mr Hamilton addressed members of Dundee Rotary Club in September 1929 and said he was convinced the “talkies will survive”.

“I further believe that most pictures will be in colour,” he added.

He was absolutely right.

The Broadway Melody was the first full-sound musical in film history.

It captured audiences like nothing else.

The Gold Rush was Charlie Chaplin’s comedic masterwork and the queue snaked the whole length of Bank Street and Reform Street.

Bonnie Scotland with Laurel and Hardy was another smash hit.

The roars of laughter from the Kinnaird could be heard across the neighbourhood.

The Kinnaird showed the biggest movies during the cinematically prolific 1940s.

In August 1944 it was taken over by J. B. Milne Theatres as the magic of the silver screen grew in popularity during the golden age of cinema-going.

Dundee girl Yvonne became Doris Day

Pamela Mulgrew, author of Let’s Go to the Pictures: Memories of Cinema in Dundee, said The Kinnaird was very popular with many Dundonians.

“My grandparents owned the Panmure Hotel in Monifieth.

“When the Vincent Minnelli musical Gigi opened in 1958, such was the popularity of the film that my grandparents organised a charabanc [long, four-wheeled carriage] to take their guests to Dundee.

“The Kinnaird used eye-catching tactics to entice movie-goers to showings.

“In 1959 the cinema used local girl Yvonne Bowden to publicise the romantic musical Pillow Talk with Doris Day and Rock Hudson.

“Yvonne greeted patrons lying on a double bed, holding a telephone in a portrayal of Miss Day in the film – certainly a unique advertising form!”

The brief boom of cinema was brought to a shuddering halt by the rise of television and the silver screens suffered widespread closures.

The building again changed hands and ran as a bingo hall from June 1962.

The Kinnaird was severely damaged by fire just two hours before an evening bingo session was due to begin on January 2 1966.

The alarm was raised by a phone clerk in The Courier office directly opposite at 5pm.

Major fire was the death knell for Kinnaird

Fifty firefighters from six stations fought flames which leapt 40 feet in the air.

A large section of the roof collapsed.

Leading Fireman Bob Nicoll was struck by falling masonry and taken to hospital.

The stage, including all the bingo equipment, was destroyed.

Seating on the ground floor and balcony were badly damaged by fire.

Water cascaded through the front doors of the building and into the street.

During the fire, the telephone rang in The Kinnaird.

It was answered and a bingo fan asked: “What are the numbers for the Golden Scoop?”

Overgate car park now stands there

The fire was brought under control after 90 minutes.

The end was nigh.

The Kinnaird had had its days of glory.

The remains were demolished in 1969 during the final phase of the Overgate Centre.

And put up a parking lot.

Conversation