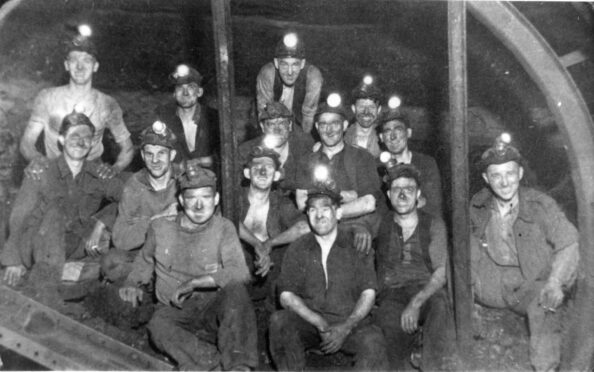

Mining employed nearly 150,000 people in Scotland in the early 1900s, producing more than 40 million tons of coal each year.

Fife was one of Scotland’s main coal mining areas with over 50 collieries coming into operation at various times from the mid-1800s.

The decline started in the 1960s and 1970s as the market changed, with what little remained of this dirty, dangerous, yet proud industry earmarked for wipe out during the miners’ strike 40 years ago.

But what’s the legacy for central and west Fife communities whose economy, culture and landscape was moulded by mining?

Has regeneration by the local authority and successive governments been successful or is the socio-economic fallout from industrial decline still being felt to this day?

As a March With the Miners parade takes place in Benarty to mark the 40th anniversary of the miner’s strike, The Courier speaks to several ex-miners working to help rebuild their communities.

‘Your community was starting to collapse round about you’

Former pit worker Tom Adams says he experienced “organised state thuggery” during the miners’ strike of 1984 as he was beaten and arrested while picketing during the bitter dispute.

Mr Adams, who worked at Frances Colliery in Dysart at the time, claimed he was punched on the back of the head and thrown into a police van before being taken to court where officers were unable to identify him.

His priority at that time was to keep a job, to put food on the table for his young family.

However, it was in the years after the strikes that the now Labour Fife councillor for the Buckhaven, Methil and Wemyss villages ward started to appreciate the community toll and wider socio-economic impact of mine closures.

“When I was growing up in West Wemyss, it was full of miners,” said the now 67-year-old, who was a miner for 23 years.

“But as more mines shut and people moved to look for work elsewhere, we were down to about 60 people in the village by the early 2000s.

“You started to realise your community was starting to collapse round about you.”

‘Huge bitterness’ in mining communities as pits closed and people suffered

Mr Adams said lack of spend in the community led to the disappearance of local shops.

While many miners got other jobs, it wasn’t the well paid, secure employment they had become accustomed to.

There was “huge bitterness” in the area, he said, which has reverberated down the generations. Community spirit, which had focused on the workplace, evaporated.

There’s also a direct correlation, he says, between the disappearance of secure long-term jobs in places like Methil and a deep rooted “living on benefits”, “poverty of aspiration” culture that has now become multi-generational in places.

When he realised West Wemyss was in rapid decline, he re-established the community council role single-handedly. He challenged the Wemyss Estate to do the village up. Now it’s “thriving”, he says.

But while the Levenmouth rail link, which opened recently, has potential to boost tourism and facilitate further regeneration, he says what remains key is for “major investment” to bring in good, secure, well paid jobs.

“If I’m being perfectly honest, I don’t think Levenmouth has improved much in the last 15 years,” said Mr Adams, who was first elected as a Fife councillor in 2007 before being beaten in 2017 and returning in 2022.

“There’s been contract work for rigs at RGC. We’ve tried the hydrogen thing, which is a longer-term project, and Diageo is an important employer in the area.

“But with the rail link coming in, I can’t see that itself bringing huge employment benefits.

“What it’ll do is improve the tourism industry and some of the local shops should benefit from the amount of people walking about.

“But it’s major investment we need. We need permanent employment that allows people to build secure lives, as the mines did.”

‘Paying the price’ for lack of employment investment in Fife

When the Central Fife coalfield shut in the 1960s, fourth-generation miner Iain Chalmers remembers the socio-economic “decimation” it had on communities like Lochgelly, Benarty, Kelty, Cardenden and Cowdenbeath.

Once “vibrant” streets were replaced by desolation.

While the electronics industry that was taking off in Glenrothes at the time took up some of the slack, many older miners found themselves on the “scrapheap”.

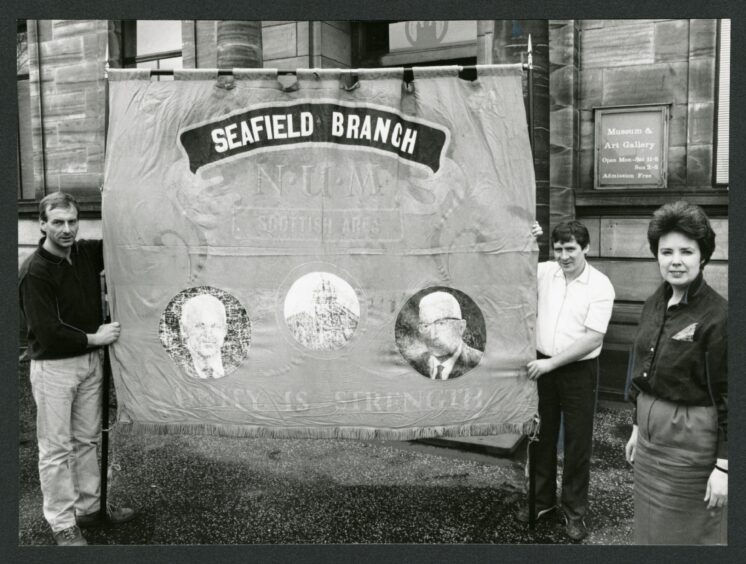

The collieries that remained became more “cosmopolitan” as displaced men travelled in from other parts of Fife.

At Comrie, for example, he worked alongside men from Kincardine, Oakley and Blairhall. At Seafield he worked beside men from Methil, Dysart, Glenrothes, Kennoway.

While community ties remained “strong” – a social solidarity that was still there in 1984 when he went on strike for 13 months – any “pit village” feel was diluted.

Today, many once dirty and noisy colliery sites have been replaced by housing developments, retail and business parks and leisure sites.

Cowdenbeath today, says Iain, is “just like any other town”. He’s got neighbours who he doesn’t know – a far cry from the close-knit community of his youth.

But as with Levenmouth, he says the former mining villages are “still paying the price” for not enough real employment opportunities being brought in.

Iain said the Tory government should have done more to create alternative employment before making the political decision to close the mines en masse.

“Groups like the Coalfields Regeneration Trust do their best,” he added.

“I certainly tip my hat to them. But if the government had not acted in a political way or a financial way and had put the infrastructure into the coalfields before they shut the pits, it would be an entirely different kettle of fish.”

Coalfields Regeneration Trust statistics paint damning picture

According to the recent State of the Coalfields 2024 report commissioned by the Coalfields Regeneration Trust, the country’s former coalfields have an older, slower-growing population; 7-10% of residents have bad or very bad health and the rate of jobs growth is half of that in the main regional cities.

There’s also a shortage of quality jobs and local brain drain with one in six of 16 to 24-year-olds claiming out of work benefits.

Meanwhile, Fife and Ayrshire/Lanarkshire are officially among the most deprived former coalfields in the UK.

Linda McAvan, chairperson of the Coalfields Regeneration Trust, said: “We are seeing positive steps towards improving the economy in the former coalfields.

“However, it is concerning that our progress is slower than in other parts of the country.

“We know that the issues affecting coalfield communities around low-quality jobs, lower wages and poor health can be tackled and the Coalfields Regeneration Trust is playing its part in addressing these issues.

“We are keen to work with political decision makers at all levels so that we can enable our communities to reach their full potential.”

Interactive mining experience at Lochore Meadows

Today, there are very few visible signs of the world that existed beneath Fife.

However, Iain, who has a long-time interest in industrial history, has been at the forefront of a campaign to create an interactive mining experience that will give visitors to Lochore Meadows Country Park a sense of life at the coalface.

Scotland’s National Mining Museum, with support from Fife Council, has given its formal backing to the project as well as agreeing to supply various industrial items from its vast collection.

The Scottish Government’s minister for employment and investment, Tom Arthur MSP, confirmed attendance ahead of the March with the Miners Parade from Ballingry to The Meedies on June 15.

A film maker from Liverpool, who is making a documentary on the role women played in the strike, will also be attending.

Meanwhile, plans are progressing for a permanent memorial dedicated to the men and women who worked at the former National Coal Board Workshops in Cowdenbeath.

Conversation