The story of the Battle of Britain has become the stuff of legend.

But what really tilted the battle against Nazi Germany Britain’s way was a secret weapon on the ground invented by the son of a Brechin joiner.

The ultra-secret technology of radar.

Although many people worked on its development, it is universally recognised that the driving genius behind radar was Robert Watson-Watt from Brechin.

Watson-Watt, in the gathering storm clouds of 1935, set out to develop a system to locate distant aircraft and, later, ships by bouncing radio waves off them and using the time lapse between transmission and echo to calculate how far away they were.

By 1935, he and his staff had produced equipment which could locate a plane up to 70 miles away and map its position with rough-and-ready accuracy.

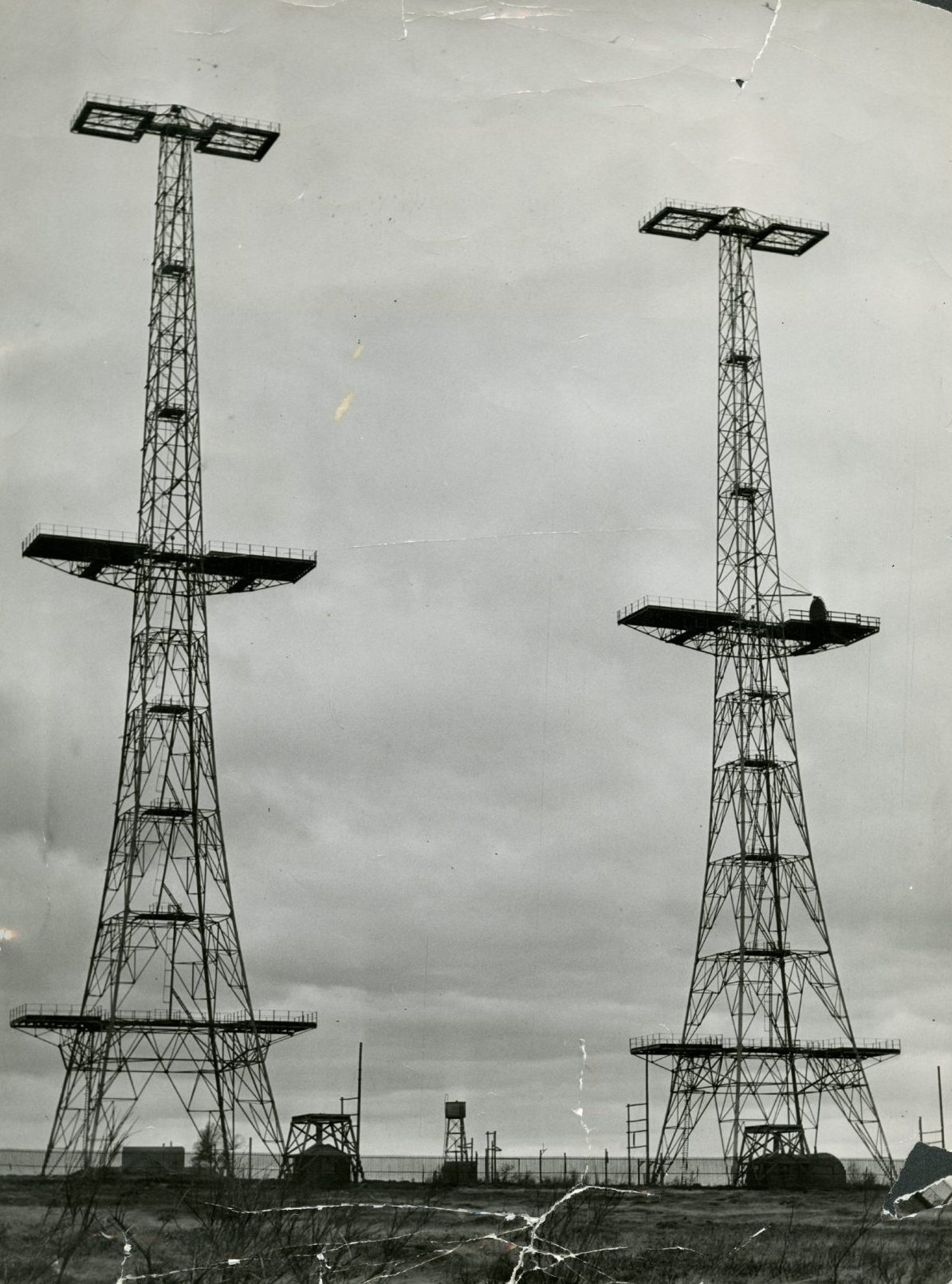

Radar stations

Thanks to him, a ring fence of early warning stations was in place by late 1939 on the Tayside coastline, including at Douglas Wood, Downie Law and St Cyrus.

Chain Home was the code name for the stations.

Margaret Bowman, author of Wartime Defences of the Tay Estuary, has chronicled the extreme importance of these sites in her latest book.

She said Douglas Wood near Monikie played a major role during the Second World War.

Margaret said there were four 350-foot transmitter towers and four 240-foot receiver towers with radar operator Len Dobson on 24-hour watch shifts in 1939.

“On a clear day, Dobson reported when he climbed up to the platform to 200 feet, he could see all the way over to East Lothian,” said Margaret.

“On August 3 1939 Dobson picked up a response on the equipment from about 120 miles away indicating what could be large numbers of aircraft approaching slowly towards the Bell Rock Lighthouse off the Arbroath coast.

“The staff at headquarters were given plotting information regularly and it transpired it was the large Graf Zeppelin airship, interested in what all the steel structures were that were lining Britain’s coastline!

“At this time the site defence was managed by two elderly Air Ministry wardens who were supported by retired regular servicemen, which was insufficient for 24-hour cover for this high-priority site.

“Just before the onset of war, a company of regular soldiers were drafted in.”

Watson-Watt and his team came to Dundee

Originally based in Felixstowe, Watson-Watt and his team moved to Dundee to ensure that its work would not attract the attention of German bombers.

Watson-Watt and his team arrived in Dundee on two special goods trains when Britain and France declared war on Germany on September 3 1939.

Margaret said they occupied the top floor, hall and workshops of the Training College.

She said the eight months Watson-Watt and his team spent in Dundee were fruitful ones before they left for a new site in Dorset.

Dundee was well situated for the work, which required an outlook over the sea.

Great strides were made in development.

Douglas Wood was one of two radar stations that detected the formation of German bombers heading for the Forth and the first air raid over Britain.

Spitfires were scrambled.

Two of the raiders were shot down on October 16 1939.

By 1940, equipment had been developed which had a range of several hundred miles and much greater precision.

Author grew up with stories of wartime

Margaret said personnel operating from Douglas Wood also tracked enemy bombers flying over to drop their payload over the docks during the Clydebank Blitz.

Margaret charts the life and times of the Chain Home radar stations in the book and many of the military structures remain visible in the countryside.

She said: “Without the technology, the expertise of the scientists and servicemen and women who manned them round the clock guarding our coast and estuaries, the events of World War Two could have had a much more different conclusion.”

Margaret was born and raised in Dunfermline.

She is the daughter of a Second World War Commando and a nurse whose first husband went missing in the war and was presumed dead.

She is now living in rural Angus, which prompted her to write what became The Lost Airfields of Angus – her debut non-fiction book which won awards from the Scottish Association of Writers in 2020 and 2021.

“Although The Lost Airfields of Angus is predominately set around the wartime airfields, both RAF and RNAS bases, I researched the various military installations which worked seamlessly with them,” she said.

“When I briefly, wrote about these facilities in the book, I realised my next book would be to investigate further what the defences were, not only on the Dundee and Angus side of the river Tay, but also across to Fife.

Dundee and its defences

“The Tay estuary was vulnerable to attack in both wars but more so in the Second World War.

“Landing craft, boats, mine-laying and submarines were an issue in the First World War and significantly so during the Second World War with the threat of invasion by air, land and sea.

“Dundee was then a major trading port in an expanding industrial city so it is an extremely important coastline which could be easily breached.

“The Tay Rail Bridge was a necessary feature which enabled transport of personnel, goods, equipment and munitions so it was vital it should be defended.

“So this did surprise me that it did not suffer attack.”

Wartime defences still standing

Margaret said the Tay Rail Bridge was heavily defended from the port area with a seaplane base and submarine base.

“Indeed, (this was) a similar situation to the Forth estuary, where following a failed attack on 1939, the Germans avoided thereafter,” she said.

“Because the land surface on either side of the river was vulnerable to attack, beach defences against tank invasion was essential.

“All down the Scottish north east coast, detachments of Polish soldiers, under the leadership of Polish General Sikorski, were given the responsibility of not only building concrete blocks and ‘dragon’s teeth’ but also the guarding of them, plus the roadblocks around Dundee.”

The anti-tank cubes called dragon’s teeth were made of reinforced concrete.

“They can be seen easily on both sides of the river, particularly at Tayport and Tentsmuir and at the harbour area of Arbroath,” said Margaret.

“There are many wartime structures still around if you know where to go and what to look for but, sadly, they are now mostly in a state of deterioration.”

Story of the Unicorn is next project

Margaret is now the Writer in Residence aboard HMS Unicorn in Dundee, which is celebrating its 200-year anniversary.

Her next book will be titled, HMS Unicorn: The Warship That Never Went To War.

“HMS Unicorn, the old Georgian warship which is currently berthed at Victoria Dock, played a significant role in both world wars,” said Margaret.

“I knew when I was researching this this would be my next book, as I had the hunger to set off digging deeper into its history.”

- Wartime Defences of the Tay Estuary by Margaret Bowman is on sale now from all good book shops.

Conversation