It was the Dundee Palace Theatre trip aged 7 that led Ian McDiarmid on a journey to a galaxy far, far away.

McDiarmid had always liked variety theatre and he was greatly influenced by comedian Tommy Morgan, who was the king of Glasgow patter.

In the 1950s the Palace in Nethergate was a twice-nightly variety theatre “where the best people see the best shows” and Morgan regularly topped the bill.

“Tommy stayed in digs at the bottom of our road,” said McDiarmid.

“Seeing him off-stage as well as on seemed to me a most glamorous thing.

“I remember meeting him at the show the first time my parents took me to the theatre, I went backstage and saw him wearing an incredible amount of make-up under very bright lights.

“I was slightly scared but incredibly fascinated by this grown man with a made-up face.”

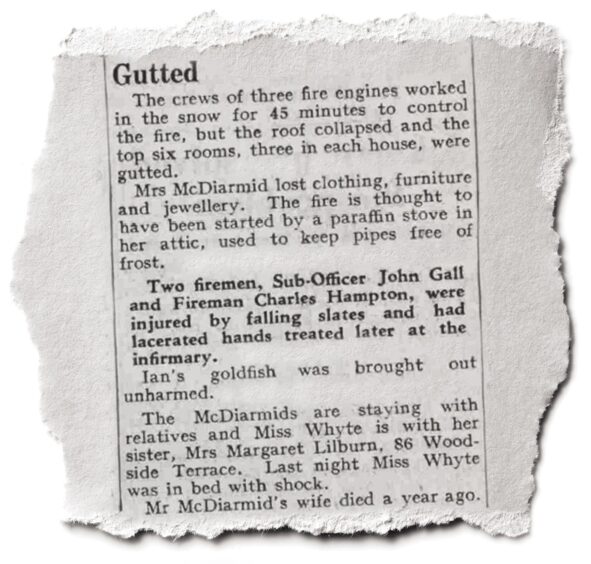

Mother’s death and dramatic house fire

McDiarmid was born in Carnoustie and grew up in Dundee.

He had a dramatic childhood.

McDiarmid was 10 when his mother died.

Then the first house he lived in burned down the following year.

All was quiet in the six-roomed house at number 10 Lynnewood Place.

McDiarmid and his father, Fred, were sitting by the fire watching TV while his grandmother Ellen was laying the table for tea in February 1955.

The Morgan Academy pupil heard a “sort of tinkling” and opened the living room door to investigate and saw fiery smoke billowing at the top of the stairs.

“I could hear a crackle, which I put down to the aerial,” said McDiarmid.

“I went upstairs where I saw flames coming from the attic.

“The place was ablaze.”

The fire was caused by a paraffin stove used to keep pipes free of frost and spread along the attic to a house occupied by Hylda Whyte.

Fred got his family out and pushed Ellen to safety in her wheelchair.

The goldfish was brought out unharmed.

Firefighters worked in the snow for 45 minutes to control the fire but the roof collapsed and the top three rooms in each house were gutted.

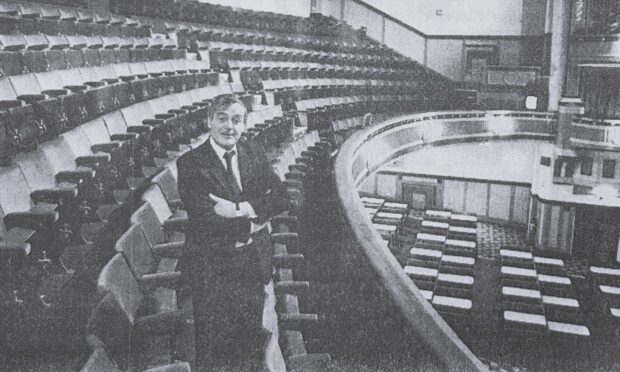

McDiarmid acted with Dundee Dramatic Society

The family moved to Baxter Park Terrace.

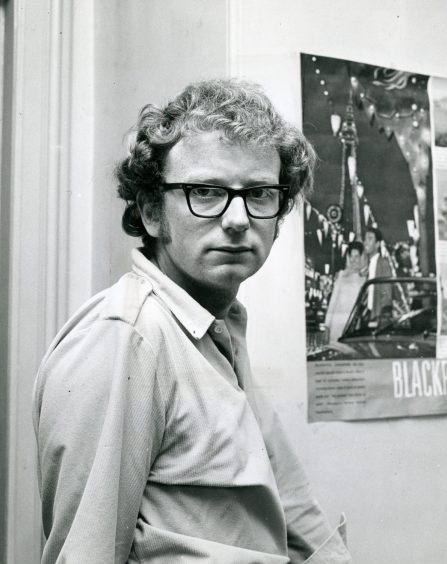

After Morgan Academy, he studied psychology and philosophy at St Andrews University to please his father and acted in Dundee Dramatic Society in between.

McDiarmid said acting always seemed to be something for other people and he took the decision to act “very late”.

He used to feel, in a strange way, that somehow he belonged on stage.

McDiarmid applied to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, as he wanted to avoid being typecast as a Scots actor only.

But he couldn’t afford RADA’s fees when they accepted him.

He applied to the Royal Scottish Academy in Glasgow, which took him.

The first year there he worked to pay his fees by labouring in a bakery and won the gold medal as the college’s most outstanding student in 1969.

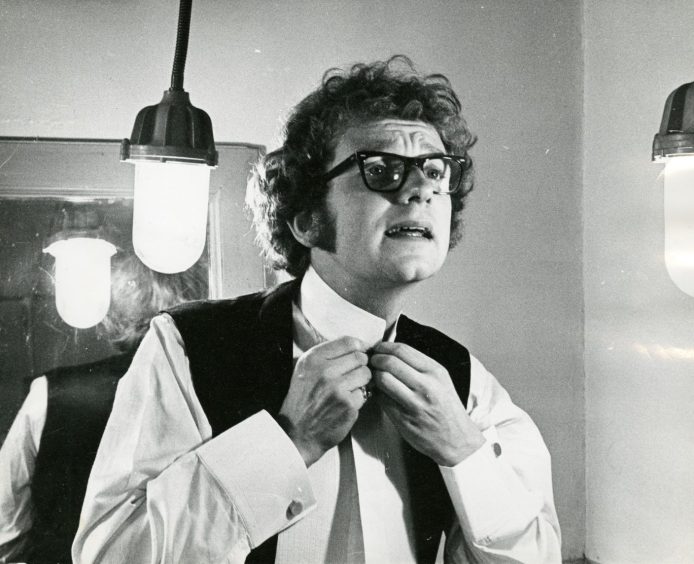

He was with several rep companies in England and did some schools programmes for TV before joining the Glasgow Citizens Theatre Company in July 1971.

He was the eldest in the company.

His first experience of playing a leading role was Galileo.

Actor earned his crust on European tour

McDiarmid went on a tour of Europe with the Citizens Company in 1972, which included one of his most unusual scenes while performing in Italy.

The Evening Telegraph reported: “While they were in Rome they performed a play, in one scene of which Ian had to slice a loaf.

“Then it was discovered that in Rome all bread is sold sliced.

“The stage manager had packed about every prop necessary for the play – butter, odd pieces of furniture and even tea bags.

“He would have had bread too, but knew it would go stale.

“The slicing of the bread was an essential part in the play so Ian and the stage manager, Robin Miskimmon, took a sliced loaf and glued all the slices together.

“Then Ian was able to slice it once again on stage.

“It would have been a bit awkward if the action of the play had called for Ian to eat the bread after slicing it.”

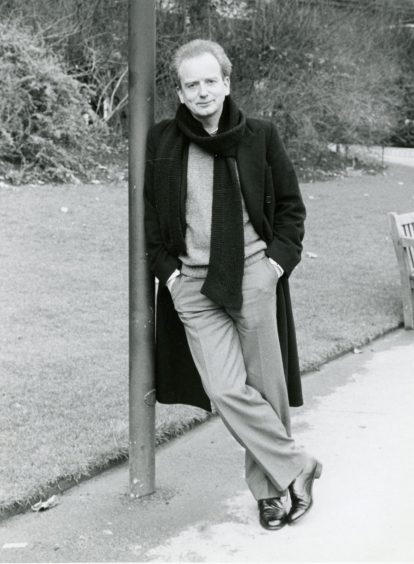

London beckoned.

McDiarmid worked at a string of major theatres.

He was with the Royal Shakespeare Company on the 1976-77 and 1984-85 seasons and combined stage work with screen appearances.

Climbing the ladder to Emperor role

McDiarmid was only once prevented from making a stage appearance when he plunged off a ladder in his London home while painting a wall.

“It went one way, I went the other,” he said.

“My first reaction was typically an actor’s one.

“I started diagnosing the way I had screamed while falling.

“I told myself it was pathetic – when I did it next time I had to make sure it was better.”

McDiarmid realised how sore he was but, undeterred, phoned the theatre to say he’d be a “little late” and would act the lead role with a broken arm.

The ambulanceman who knocked on his door had other ideas.

He discovered McDiarmid had broken his arm, wrist, elbow and hip.

He spent three months in hospital.

But you can’t keep a good actor down.

McDiarmid received an Olivier Award for Best Actor in 1982 for Insignificance at the Royal Court before George Lucas offered him a role in Star Wars.

It was thanks to McDiarmid playing an old, dying man in Sam Shepard’s Seduced.

Lucas and the casting director for Return of the Jedi saw the play and were convinced that McDiarmid was the perfect actor to play Emperor Palpatine.

He was.

McDiarmid underwent an astonishing transformation to become the galaxy’s age-old enemy including yellow contact lenses which stung his eyes.

His performance solidified Palpatine as an enduring symbol of ultimate evil.

Ian McDiarmid returned to Star Wars role in 1999

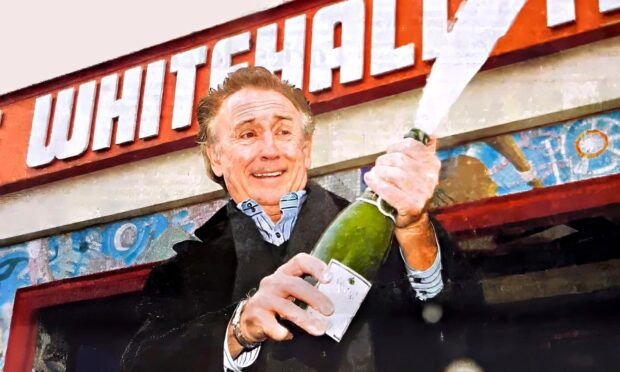

He was subsequently co-artistic director with Jonathan Kent of the Almeida Theatre.

They transformed the London venue and persuaded stars like Juliette Binoche, Cate Blanchett, Ralph Fiennes. Liam Neeson and Kevin Spacey to work there.

McDiarmid also worked with George Lucas on the 1992 television series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles when he played Professor Levi.

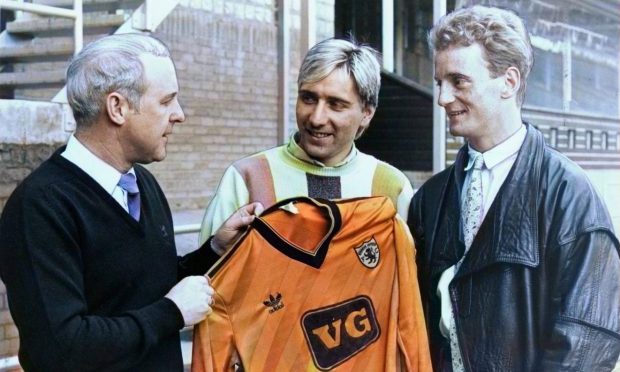

McDiarmid then returned as a young version of Palpatine in the Star Wars prequels from 1999.

These saw him star alongside Ewan McGregor, Liam Neeson and Natalie Portman.

They were set decades before the original films.

Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith was the best movie of the prequel trilogy and included the transformation of Palpatine into the disfigured Emperor.

His performance was hammed up to the hilt.

But almost everybody loved it.

Movies were great but his first love remained the theatre.

In 2006 he won a Tony Award in New York for Faith Healer at the Booth Theatre.

He was also on television in Inspector Morse and Chernobyl: The Final Warning.

Other small-screen roles include Hillsborough, Touching Evil, Spooks, City of Vice and Margaret.

Movie credits included Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Gorky Park and Sleepy Hollow.

An Ian McDiarmid statue would carve famous Star Wars role in stone…

And in 2019’s The Rise Of Skywalker, McDiarmid came back one last time as Palpatine in the final film in the sequel trilogy.

Fandom is a powerful thing in the digital age.

Arbroath student Hunor Deak started a crowdfunding campaign afterwards to build a statue of Palpatine in McDiarmid’s home town of Carnoustie.

It has struggled to get off the ground but is there time for another comeback?

The great man himself would probably not be opposed to the statue idea given the role made him part of the money-spinning sci-fi franchise.

“The Emperor’s been good to me,” said McDiarmid.

“He’s been terrible to everybody else, but good to me.

“That’s his one redeeming quality.”

Conversation