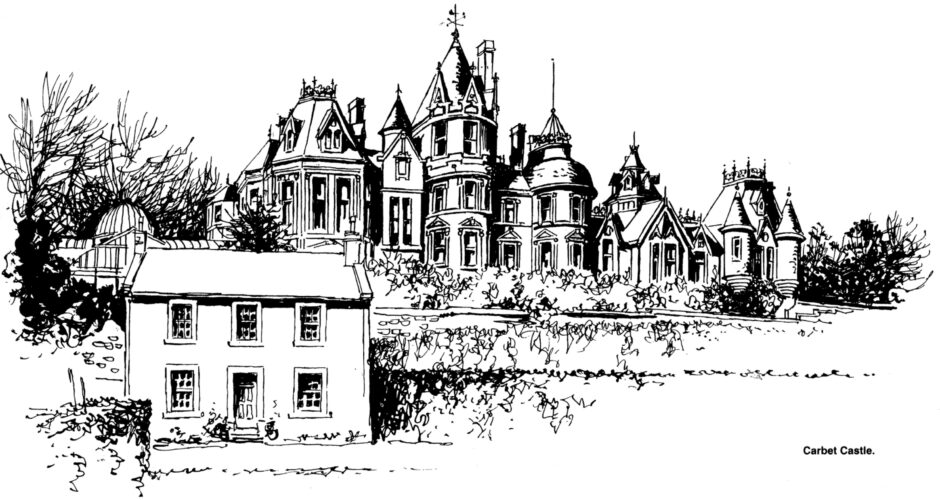

Carbet Castle once stood proudly in Broughty Ferry before being torn down in 1984 after many years of complete dereliction.

The Gothic mansion at the foot of Camphill Road was one of the first buildings to attract the eye of the stranger in Broughty Ferry.

Originally known as Kerbat House, Carbet Castle was built in 1861 for Joseph Grimond who ran the Bowbridge Jute Works with his brother Alexander.

Messrs Grimond were among the early pioneers of the jute carpet trade and sold them in branches based in Manchester, London and New York.

While their factories in Dundee were driving industry, many jute barons set up home in Broughty Ferry – then outside the city boundaries and part of Angus.

That meant they were able to avoid paying Dundee’s higher tax rates.

The Victorian era flaunted excess

They built extravagant homes in what was once one of the richest suburbs in Europe.

Grimond extended Carbet Castle with richly decorated east and west wings designed in French Renaissance style by Thomas Saunders Robertson.

Messrs Grimond had a camel’s head as their trademark.

Grimond chose a carved stone camel’s head as the centrepiece of the archway of Carbet Castle which was among the beautiful ornamental designs.

No expense was spared

Carbet Castle comprised a drawing room, dining room, boudoir, tower room, breakfast room, library, school room, billiard room and smoking room.

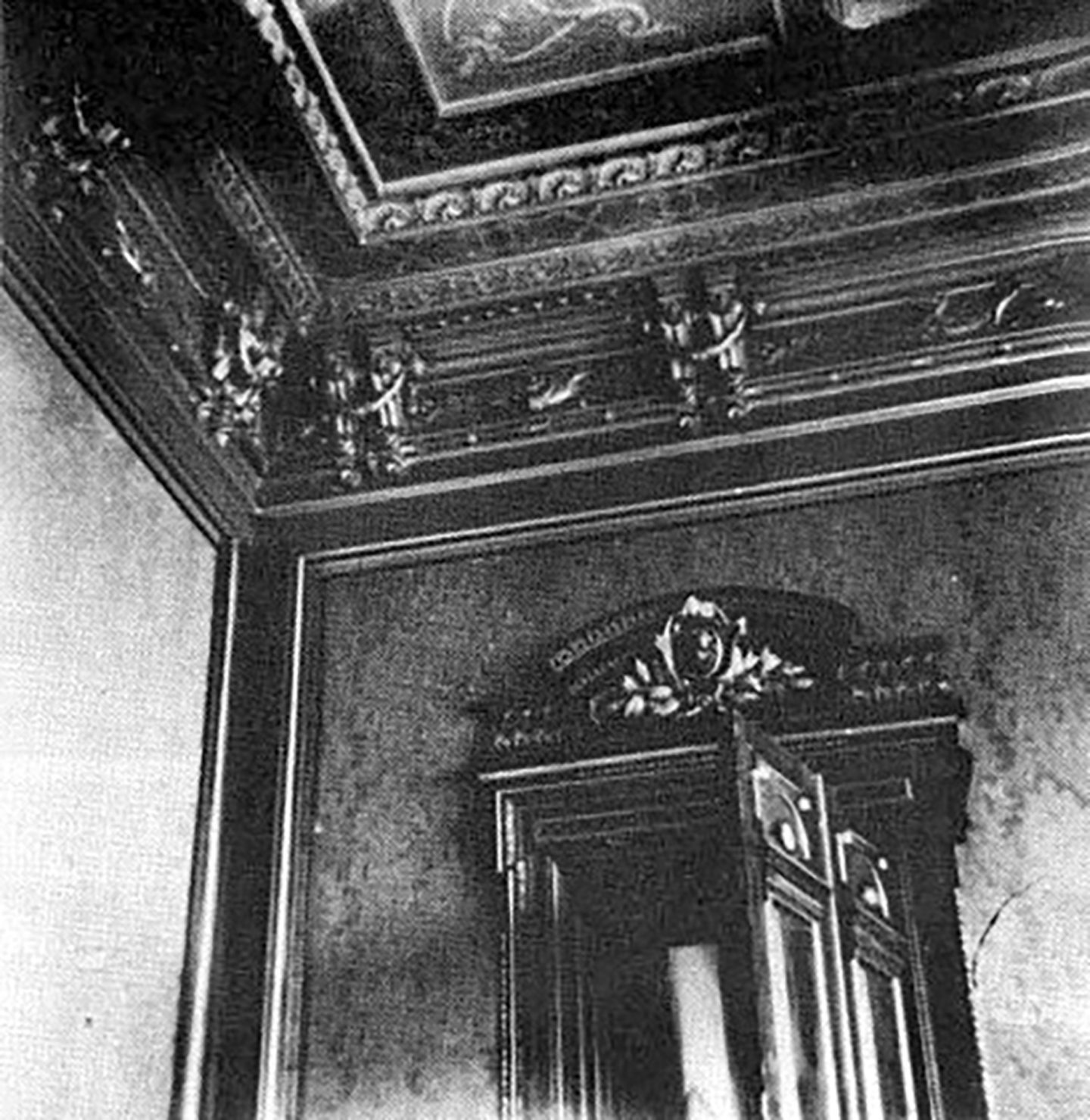

It featured two ornament ceilings painted by famous Parisian artist Charles Frechou.

His other major work was the ceiling of the Paris Opera House.

There was a housekeeper’s sitting room, nurseries, nine bedrooms, four servants’ bedrooms, butler’s pantry, servants’ hall, kitchen and laundry room.

Grimond was a devoted horticulturist.

He pursued his “pleasant and elevating pursuits” in adjoining conservatories, greenhouses, vineries, peach-houses and a kitchen garden.

A millionaire’s row in Broughty Ferry

There was rivalry in trying to build something bigger and better than each other.

George Gilroy was determined to outshine these efforts.

The Gilroy Brothers’ Tay Works in Lochee Road was the finest single block of factory buildings in the town and was topped by a statue of Minerva.

Gilroy bought a higher and a larger site in Broughty Ferry.

He used the family’s new wealth to build the mansion of Castleroy in 1867 and brought up Bannockburn stone by the hundred tons.

Gilroy brought a team of artists from Italy to outshine the work of Frechou.

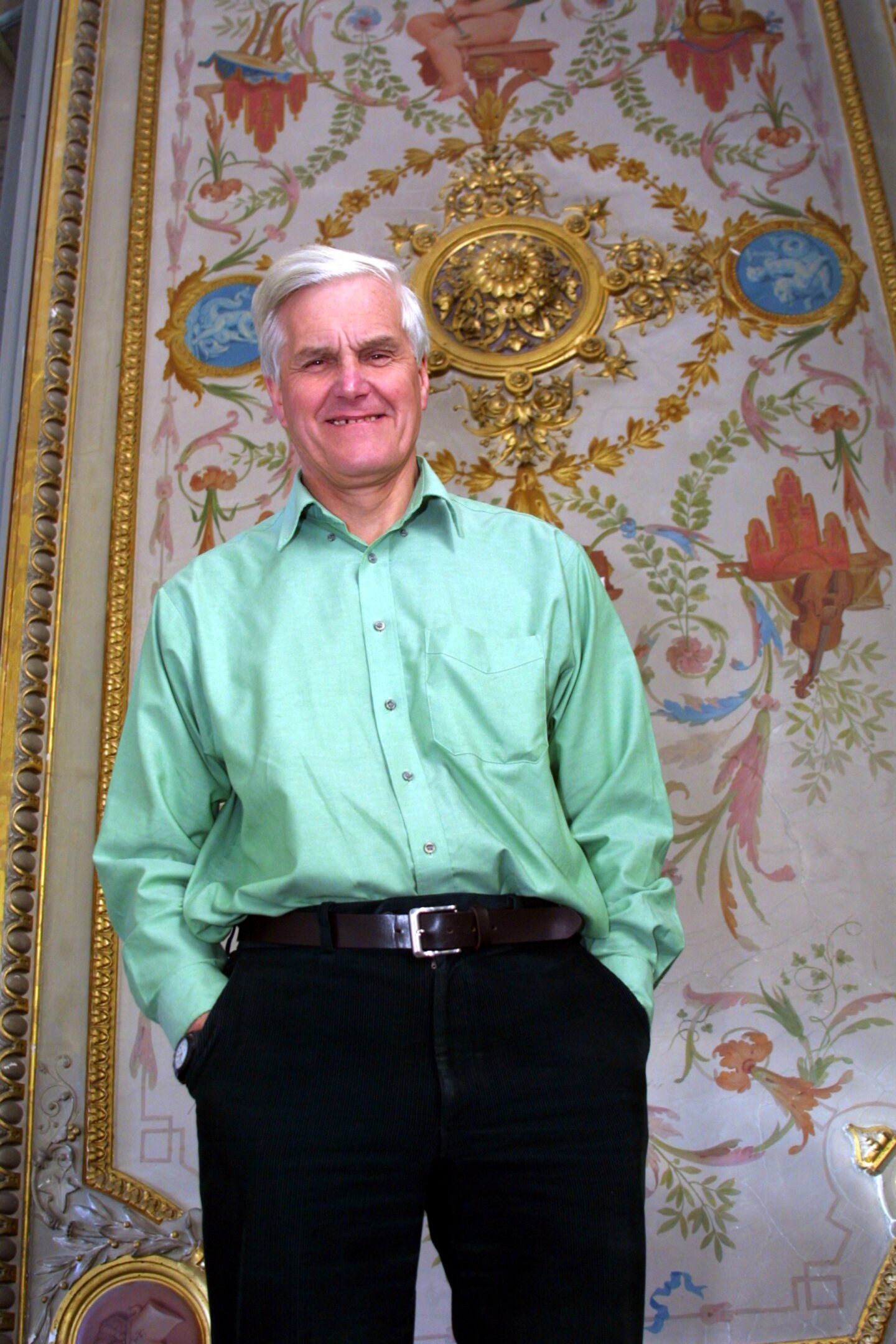

Kenneth Baxter, from the University of Dundee Archive Services, said Carbet Castle and Castleroy were perhaps the most iconic of these lavish mansions.

He said: “From surviving photographs and illustrations it is clear that in their heyday they must have been a striking site rising above Broughty Ferry.

“They would have been a clear demonstration to all of the success and status of their owners.

“They were an important part of Dundee’s history.”

Meanwhile, Grimond was keen to expand his property empire.

He bought Kinnettles Castle in Forfar and split his time between his lavish homes.

The jute palace rivalry ended when Gilroy died at the age of 76 at Castleroy in 1892.

Grimond was also in poor health and getting older too.

He made a short visit to Liverpool to visit his eldest married daughter when he suffered a brain haemorrhage and died at the age of 73 in November 1894.

Carbet Castle was sold for £2,500 in 1922

Grimond made his final journey from Carbet Castle.

He was buried in Barnhill Cemetery.

It was the same graveyard where Gilroy met his maker.

Grimond left Carbet Castle and Kinnettles Castle to his widow and an annuity which paid an income of £4,000 per year for the rest of her life.

Information from the Valuation Rolls for 1895 showed Carbet Castle was worth £285.

Castleroy was valued at £405.

The jute industry was hit by a series of booms and slumps in the 19th Century, before falling into decline in the 20th Century.

Carbet Castle passed down through the generations.

It was put up for sale in 1922.

It failed to sell and was put up for auction at reduced price and bought for £2,500.

The Courier said it was a “meagre price” for this “house of wonder“.

It read: “It would be difficult to state what it has cost to build Carbet Castle and lay out its grounds, but several thousand pounds must have been involved.

“One authority puts it at £50,000.

“Its extension and beautification was the chief hobby of its late owner, who always liked to have tradesmen employed upon some scheme.

“A well-known builder in the city stated that no private individual would contemplate erecting such a mansion nowadays, because it did not possess the sort of ground one would desire with a mansion of its dimensions.”

Historic house would face wrecking ball

The purchase was made by Messrs John Scott and Son.

They were joiners and builders from Fyffe Street in Dundee.

There was a suggestion the mansion would be converted into a boarding house.

The reality was far more brutal.

The building was largely demolished between the wars and by the 1950s there only remained the west wing and an earlier rear service block.

Both were in ruinous condition.

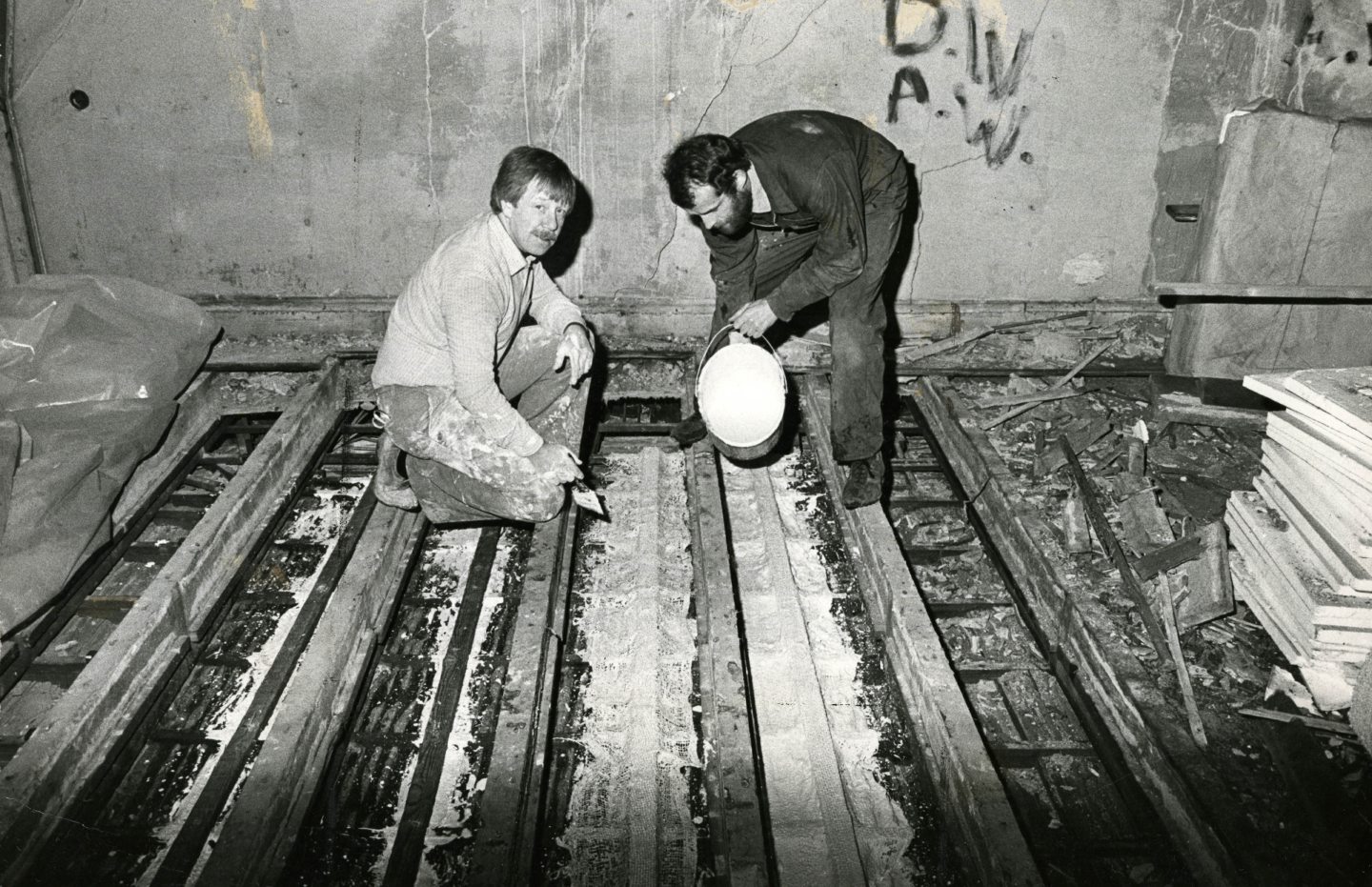

A photographic survey was carried out in 1953 by David Walker for the Historic Monuments for Historic Scotland.

Carbet Castle remained standing for another 30 years.

By the time it was destined for demolition it was in a deplorable state.

The ceiling was saved at the last minute.

Dundee Civic Trust raised more than £12,000, which paid for a team of professionals to remove the two ornamental ceilings.

Although the larger of these was the more interesting and significant, it was the smaller one for which the Trust first found a home.

The ceiling was placed on the stair of the Matthew Building at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art as an example of Victorian design.

Despite being offered free to a good home, no takers were found for the larger ceiling, which was stored at the former Stobswell Bakery warehouse.

The last remaining section of Carbet Castle was demolished in 1984 to make way for an ambitious plan to build 29 houses on the plot.

The housing project was vetoed by the Scottish Office after a planning appeal.

Construction finally started on 15 flats on the site in 1997.

Part of ceiling almost ended up in Dublin

The larger ceiling was moved to permanent storage by Historic Scotland at Stanley Mills in 2004 when the Stobswell warehouse was demolished.

The smaller ceiling stayed for over 25 years in the Matthew Building until the college modified the entrance and it was latterly stored in a container.

Dundee Civic Trust former chairman, Jack Searle, said considerable efforts were made to find it a new home.

Places considered included the V&A and Verdant Works.

At one point, it almost went to a private house in Dublin with links to James Joyce.

The High School of Dundee wanted to install the ceiling in part of the former post office building.

The expense proved insurmountable, however.

Unfortunately, when pursuing this, an examination by conservation consultants revealed the ceiling was damaged and extremely fragile.

They found the ceiling had limited architectural or historic value and disposal was the only way ahead in February 2019.

Another sad footnote in the story of this once-majestic jute palace.

Conversation