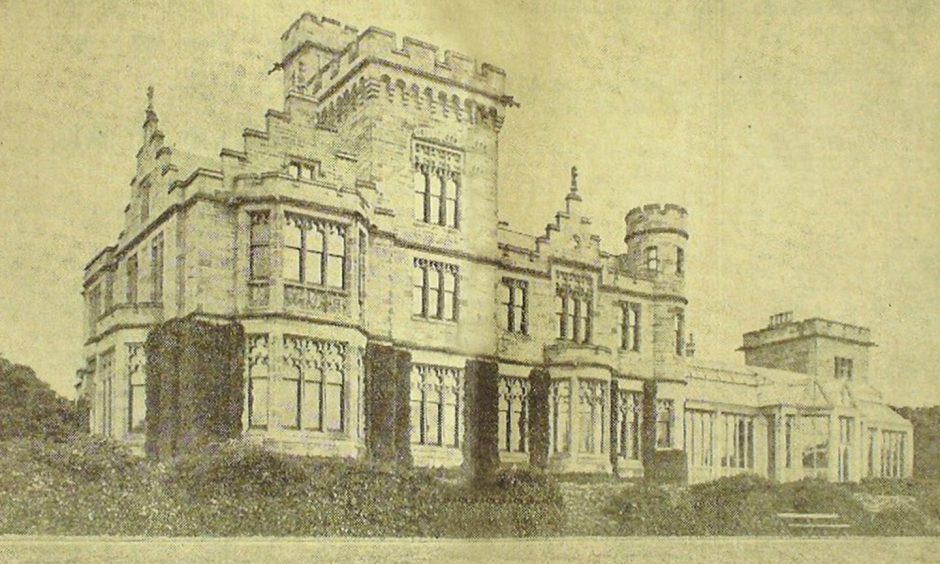

Castleroy mansion house in Broughty Ferry boasted 100 rooms and was once Dundee’s grandest jute palace.

The property had 365 windows – one for each day of the year.

Castleroy stood on almost the highest summit of Balgillo Hill for 84 years.

On a clear day you could see across the Tay to St Andrews.

In the end, it was blown to smithereens.

Jute barons built palaces in Broughty Ferry

While their factories in Dundee were driving industry, many jute barons built extravagant homes in what was once the richest square mile in Europe.

The Gilroy Brothers’ Tay Works in Lochee Road was the finest single block of factory buildings in the town and was topped by a statue of Minerva.

Minerva was the Roman goddess of wisdom, medicine, commerce, handicrafts, poetry, the arts in general and, later, war.

There was rivalry in trying to build something bigger and better than each other.

George Gilroy used the family’s new wealth to build the mansion of Castleroy in 1867 and brought up Bannockburn stone by the hundred tons.

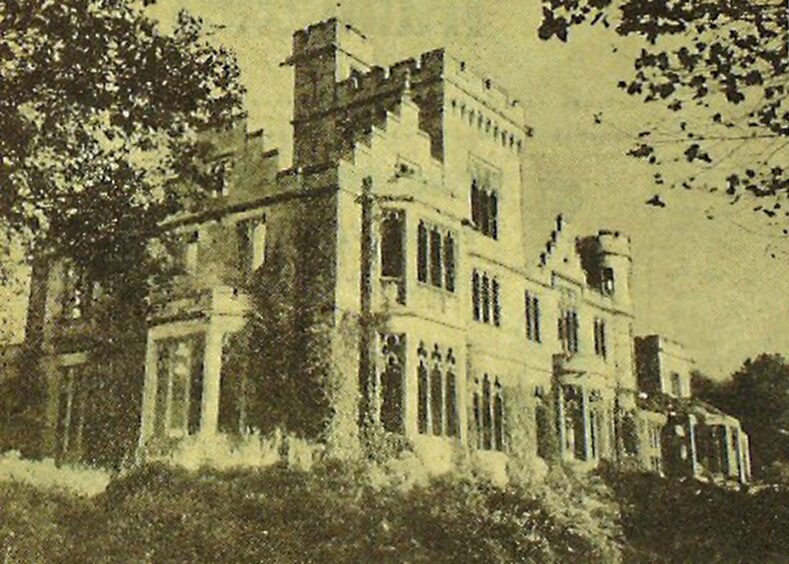

The mansion house was intended to, and did, outshine the huge Carbet Castle of the Grimond family, which was lower down the hill, in Camphill Road.

Castleroy incorporated the Gilroy name.

It was built to the Tudor designs of architect Andrew Heiton from Perth.

The £35,000 contract was secured by Thomas Steven from Broughty Ferry.

The jute palace rivalry ended when Gilroy died at the age of 76 at Castleroy in 1892.

He was entombed in a magnificent mausoleum at Barnhill Cemetery.

Castleroy was offered to eight relatives

Castleroy passed down to Alexander Bruce Gilroy.

Meanwhile, Dundee lost its virtual monopoly on production and Gilroy Brothers amalgamated with other jute firms including the Grimond family in 1920.

The bitter rivals became brothers in arms with the industry in decline.

Alexander Bruce Gilroy died in 1923.

Successive heirs of the estate were offered the house and grounds with £40,000 to maintain it as a residential property.

All eight of them turned it down.

Under the terms of the will, the grounds and mansion house were to be made over to the local authority when life rents of relatives were exhausted.

The grounds, it was suggested, might be used as a public park with the house to either be used as a home of rest, hospital or convalescent home.

A total of £10,000 from its income was also to be gifted to maintain it.

It was run by the Gilroy Trustees until it was formally offered to the council in 1945.

But the offer was unanimously rejected following a site visit.

Labour council decided to accept the gift

Kenneth Baxter, from the University of Dundee Archive Services, said there was concern from councillors that it might be a costly liability.

Castleroy had fallen on hard times after the war, when it saw service as military accommodation and was used by Polish forces.

For a while it was occupied by squatter families.

“Then the November 1945 election greatly changed the composition of the council and brought a Labour majority, with many of the new councillors being more inclined to accept the gift,” said Dr Baxter.

“The idea of a home for the elderly was also mooted, as was the prospect of it becoming a convalescent hospital.”

In 1946 the Corporation agreed to the gift.

It was subsequently used by Dundee Corporation for emergency housing.

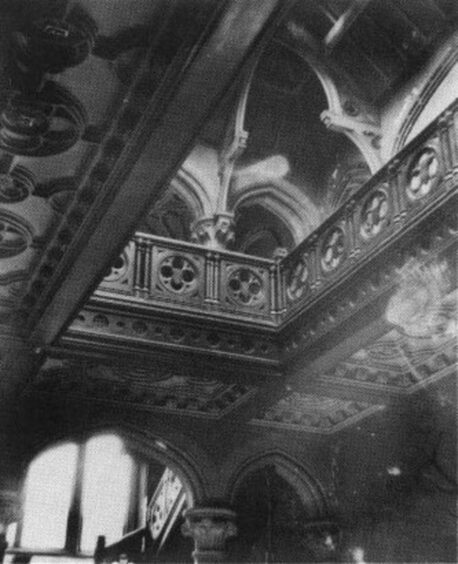

However, years of inattention meant Castleroy was riddled with rot in the basement.

City architect James MacLellan Brown said it was the worst case of dry rot he had ever seen when he reported to Dundee Housing Committee in December 1947.

It was Merulius lacrymans, which was caused by dampness and bad ventilation.

It was first noticed as a thin film, like a spider’s web.

Dry rot had taken hold of Castleroy by 1947

Mr Brown said the whole building might be utterly ruined if it was left.

Councillor James Gillies suggested it would be throwing good money after bad to fix it.

“It is worth noting that Councillor Gillies, who represented Ward 11, which Castleroy was in, was perhaps the biggest sceptic of the council accepting it in 1946,” said Dr Baxter.

“He was a senior figure on the council.

“In 1951 he noted that the £10,000 legacy that had come with Castleroy had not been enough to make it solvent and as a result the council ‘had taken on a nice liability’ which was ‘an absolute monument to dry rot, nothing else’.

“The dry rot issue does seem to have been a serious problem and at a time when new housing was needed, spending large sums on maintaining a mansion would have surely been politically unpopular.”

The fungus became extensive.

More than £400 was spent to eradicate an outbreak of dry rot in the kitchen.

It was no use.

The dry rot spread to the main part of the building by January 1953.

“This, unfortunately, looks like a doomed building,” said Councillor Gillies.

Dundee Corporation sought powers to demolish the mansion on the grounds that the £10,000 fund was inadequate for proper maintenance.

Under the original gift they could have only done this to create a park, but it was felt with the recent Dawson Park development, a new park was not needed.

Mansion house was stripped and blown up

“The Corporation felt the conditions of the agreement meant they could not put the house or grounds to a useful purpose,” said Dr Baxter.

“However, in 1953 the Gilroy Trustees, who argued the Corporation had voided the agreement, were given the house and grounds back by the Court of Session.

“The trustees did, of course, sell it for demolition.

“Houses were built by a private developer.

“It all seems like a series of missed opportunities.”

Castleroy was blown up by Dundee-based demolition contractor Charles Brand.

A series of small explosions were used because a full dynamite charge would have transmitted shockwaves to Forthill housing scheme.

The work was completed in August 1956.

The archway, known as West Lodge, was all that remained.

Castleroy treasures might have survived

The Castleroy site was divided into several plots of about an acre each.

Private houses were erected on the site.

Not everything from the past was destroyed.

A three-foot stone lion was found intact in the rubble and saved.

“It looks like the demolition was protracted,” said Dr Baxter.

“There are lots of references in 1954 to work being started, but when the flagpole was taken down in 1955, it was said that the rest of the building was to be demolished soon, but the actual final demolition of the shell was in August 1956.

“My best guest would be they stripped it down and then blew it up.

“There seems to be quite a few references to building materials being sold from the site over the period 1954-1955, including oak panelling and flooring and marble fireplaces and slates and pipes and even sinks and washtubs.

“I suspect they were quite careful about taking out anything of value they could sell.

“I think it is likely there are people who have bits of Castleroy in their house.”

Castleroy Road was named after the sumptuous mansion in the 1920s.

The street name remains a nod to the jute boom that made untold fortunes for many of Dundee’s industrialists.

Conversation