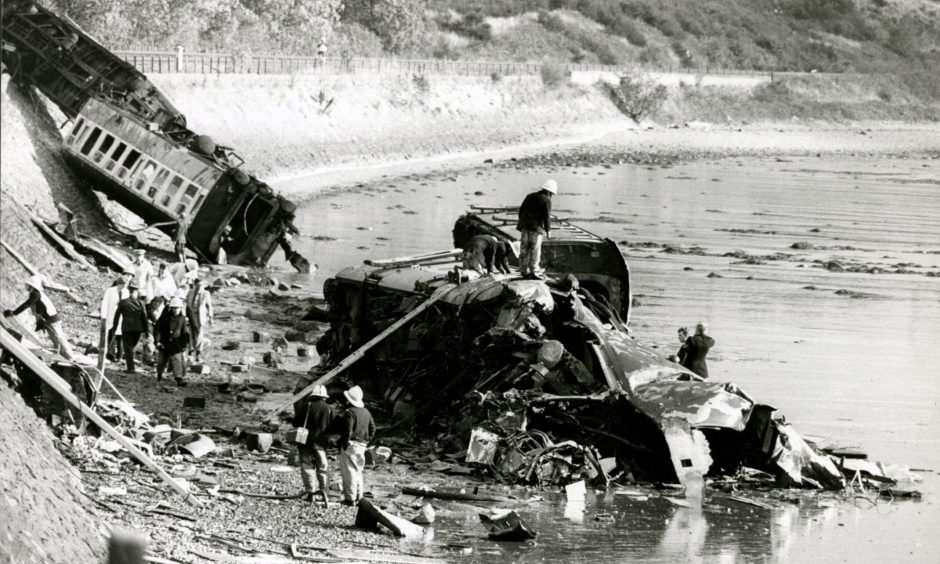

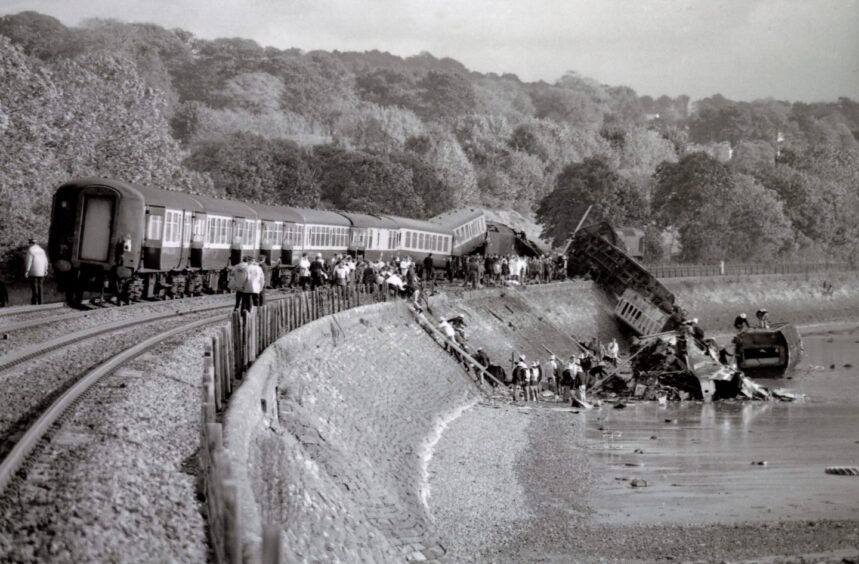

These photographs reveal the full severity and horror of the Invergowrie rail crash which left 51 injured and five dead.

Some have never been seen before.

The 8.44am Glasgow to Dundee train, hauling five carriages, broke down just after it left Invergowrie around 11am on October 22 1979.

It had lost power three times during the journey and was 22 minutes late.

Ten minutes later, the 9.35am Glasgow to Aberdeen express, travelling at around 60mph, ploughed into the rear of the stationary train.

Few passengers, if any, could have been aware that death and destruction were only seconds away as the express rounded one final bend.

There were 180 people on board both trains

The accident happened within sight of the Tay Bridge which was the scene of history’s most famous rail disaster 100 years before.

The driver and assistant driver, Robert Duncan, 52, from Tayport, and Billy Hume, 20, from Fintry, Dundee, died despite braking desperately after spotting the train.

The force of the impact threw the last two carriages of the stationary train across the sea wall and onto the muddy foreshore of the River Tay.

The first carriage was derailed and drawn towards the river.

The second and third were projected onto the sea wall but remained coupled.

Dr James Preston from Birmingham and Kazimierz Jedrezejczy from Poland had been at the rear of the stationary train and were killed instantly.

They were the only two passengers in the rear coach.

May Morrison, 76, from Perth died the following month from acute pancreatitis in Ninewells Hospital after suffering abdominal injuries in the crash.

The death toll would have been higher if the tide had been in.

It was also fortunate the train was not heavily loaded with passengers.

Eyewitness recalled impact and sound of rail crash

John Chalmers stood in his garden overlooking the line on Perth Road.

He could see the stranded train.

The express was less than 400 yards away when he caught sight of it through a gap in the trees and realised the incoming loco wasn’t going to stop in time.

He said: “I thought, good grief, it’s never going to stop.

“There was no sound of brakes, then the engine ploughed underneath the last carriage, throwing them into the air like matchboxes.

“The impact and sound were colossal.

“I could see two of the carriages rearing up and then disappearing.”

Gordon Hally from Perth was the British Rail catering manager on the 8.44am.

He described an “enormous impact” which was totally without warning.

“Everyone inside was flung around,” he said.

“When things quietened down I discovered our carriage had slewed right across the track and was hanging out over the bay.

“I could hear rescue workers starting to call to the carriages and I told them to get others out first who were injured.

“We all managed to climb from the door on to the track.”

Perth woman’s leg was amputated at scene

Ken LeDez was 22 and a final year medical student at Dundee University.

“I managed to get out of the end of the carriage which had broken off and ended up in mud up to my knees,” he said.

“It really was amazing there weren’t any more injuries.

“I found a woman who had her leg ripped off but she was still conscious.

“I had to try to stop the woman from bleeding or she might have bled to death.”

Ken comforted 73-year-old Agnes Aitken from Perth, and, aided by a nurse who was also on the train, used improvised bandages to stem the flow of blood.

Local residents alerted the emergency services and the first unit arrived at 11.20am.

Police, firefighters and paramedics used ladders and ropes to reach the carriages and 51 people were taken by ambulance to Dundee Royal Infirmary.

The uninjured passengers were taken from the site to Dundee by bus.

The Tay Bridge rescue craft assisted firefighters to recover the last body from the rear coach of the 08.44am train which had become partially submerged.

The Courier carried a list of casualties being treated in hospital, with a full description of

their injuries, condition and home address.

Dundee United winger Doug Wilkie was among the injured that day.

The 23-year-old was paralysed from the waist down and had to give up playing football.

The Courier’s coverage of the 1979 Invergowrie rail crash

The newspaper coverage included a first-person piece written by a “Courier lady reporter” who had been travelling on the train from Glasgow to Aberdeen.

She described experiencing the “sound of silence” following the accident after being thrown against the empty seats opposite and down on to the floor.

“It is a unique sensation,” she said.

“For, out on the track, just minutes after the crash, there was not a sound to be heard.

“It was an eerie feeling.

“I knew there had to be people trapped in the tangled wreckage of carriages some 25 feet below.

“But there was no movement, not a sign of life.

“Surprisingly, there was no screaming, no anguished cries for help, none of the expected groaning from those injured and trapped in the mess of metal.

“It was some time before I heard the almost plaintive cry of a child down below.

“It was the first sign that anyone was still alive.”

Acts of courage and humanity on show

She said the best side of humanity was also seen on that terrible day.

“What is indelibly fixed in my mind is the way that tragedy and crisis bring everyone closer together,” she said.

“Complete strangers comforted each other and were prepared to do anything to ease the suffering.”

The rail crash made front page headlines across the UK.

It led the BBC Nine O’Clock News with Michael Buerk reporting from the scene.

Blame for the crash was eventually attributed to Robert Duncan after a fatal accident inquiry ruled he had misread an imperfect signal at Longforgan.

However, many felt it was unfair to blame Mr Duncan.

The signalling at Longforgan was basic and lacking in many safety features.

A deficient semaphore did not return to danger and the signal post bracket itself had been bent and this contributed to it giving a misleading aspect to the driver.

The line was reopened the next day with a 5mph speed restriction.

Two years later, the crash was still making the news.

The Department of Transport published a report which blamed the driver’s error but highlighted deficiencies of a “potentially serious nature” at Longforgan.

The 1979 accident had a profound and lasting effect on the local community.

It’s been 45 years but the pictures are just as shocking as they were back then.

Conversation