Think of Victorian detectives and fictional names like Sherlock Holmes often come to mind.

However, historian Dr Sara Lodge of the University of St Andrews has unearthed a fascinating alternative story.

She’s been researching the real-life female detectives who worked in the shadows of Britain’s crime-ridden 19th-century streets, including Dundee.

Her new book, The Mysterious Case of the Victorian Female Detective, includes details of how Dundee’s strong-willed, daring women were at the forefront of a field traditionally dominated by men.

What work did Victorian female detectives do in Dundee?

The women would often handle cases in ways that challenged and defied the conventional norms of their time.

Yet despite their important role, she’s concluded most people today are not aware of their existence.

Controversially, they were often not given true recognition in their time either.

“There were different kinds of female detectives working across Britain in the 19th century,” said Dr Lodge.

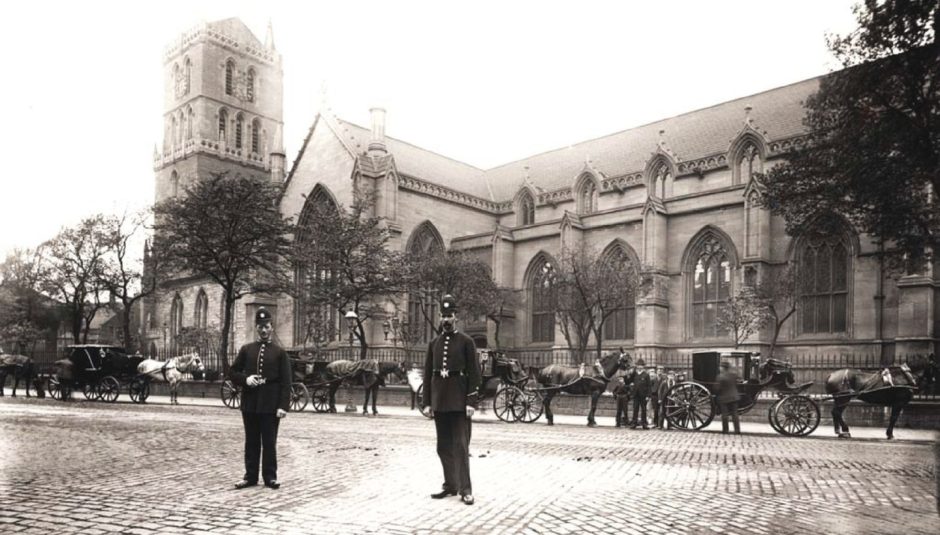

“Some of these women were working in police stations. They were often working as kind of searchers in the station. They’ll be searching female suspects, their clothes, their bodies.

“Then as now, just like drug mules, they’d conceal things under their tongue, or sometimes in more private parts.

“We have evidence of women also being used in kind of sting operations, and there’s evidence of this going on in Dundee in the 1870s.

“But often they were not given the credit they deserved.”

What are the most memorable cases involving female detectives in Dundee?

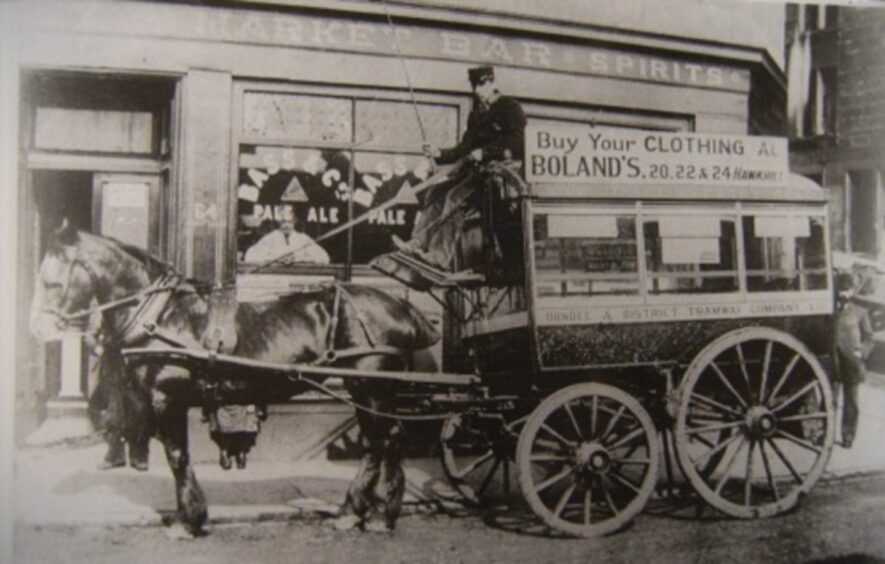

In 19th-century Dundee, women’s roles were expanding beyond the home, though often in subtle and covert ways.

While societal expectations limited many women, the city was home to a fierce breed of local heroines and undercover operatives.

One such woman was Anne Hay or Fraser, a “turnkey” in the Dundee Police office in the 1870s.

Delving into the newspaper archives, Dr Lodge discovered a variety of stories.

These included the time Hay was sent out with an empty bottle to pose as a customer, tasked with gathering evidence against an illegal whisky dealer.

She was part of an operation that, to modern sensibilities, skirts the line between investigation and entrapment.

But for the city’s bustling underworld, Hay’s undercover work helped to curb illegal activities.

“The image of a demure Victorian woman fades quickly when confronted with the likes of Isabella and Jean Stewart, two Dundee sisters who, in 1866, sprang into action after their 67-year-old father, Donald Stewart, was mugged on a Saturday night,” said Dr Lodge, referring to another case.

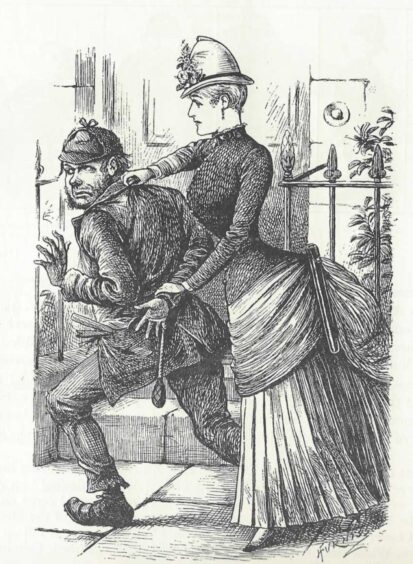

“Rather than shrinking from the threat, the Stewart sisters tracked down the thief in a pawn shop, withstanding physical assault as they held him down until police arrived.”

For Dr Lodge, these stories exemplify how Dundee women were willing to put themselves in harm’s way to stand up for their families and communities.

Complicated life of female sleuths

The work of Dundee’s female detectives was challenging and morally complex.

Dr Lodge’s research reveals that these women’s roles weren’t limited to heroic citizen’s arrests; their work could be gritty, ambiguous, and rife with ethical pitfalls.

In cases involving sting operations, Dundee’s female operatives would sometimes act as bait to lure criminals into committing a crime.

This approach raises questions of entrapment versus genuine justice.

From observing adulterous spouses to infiltrating suspected criminals’ inner circles, their assignments were often morally taxing.

In some cases, female detectives faced community criticism.

While figures like Isabella and Jean Stewart were lauded by the Dundee Courier as symbols of wit and bravery, others, like Anne Hay, encountered ambivalence and moral judgment.

Dr Lodge points out that Dundee’s working-class theatre audiences were eager to see heroines on stage, like the “gun-toting” female detective popularised in Victorian plays, embodying a brash, larger-than-life version of these real women.

An age of constraints and determined defiance

Dr Lodge’s research highlights the tremendous limitations placed on female detectives of the time.

The 1857 Divorce Act marked the beginning of a boom in private investigative work, particularly for women like Antonia Moser and Kate Easton, both of whom launched detective agencies of their own.

Her findings suggest that Moser, an entrepreneurial divorcee, and Easton, an actress-turned-sleuth, used their expertise to assist fellow women, exposing marital infidelity and helping women navigate new divorce laws.

Yet, even these female investigators weren’t immune to the ethical quandaries of Victorian society; their surveillance work in adulterous liaisons often pitted them against other women.

How did Dr Lodge start uncovering history’s hidden female detectives?

Dr Lodge’s groundbreaking research began in 2012, sparked by a surprising revelation.

Two fictional casebooks titled The Female Detective and Revelations of a Lady Detective had been republished by the British Library.

When she read that “no female detectives existed in 1864,” Dr Lodge couldn’t accept this claim.

Fuelled by curiosity, she delved into newspaper archives, uncovering advertisements and case records documenting real female detectives’ work.

What she found has transformed our understanding of Victorian policing, casting women in roles that challenge the long-held assumption that policing was an exclusively male domain until the early 20th century.

Digitised newspaper archives were instrumental in Dr Lodge’s work, revealing cases that traditional history had overlooked.

Dundee’s local court records and police reports yielded countless tales of women like the Stewarts and Hay, who operated on the frontlines, sometimes barely acknowledged or compensated by the police forces they served.

Sara Lodge’s book, The Mysterious Case of the Victorian Female Detective, is published by Yale University Press.

Conversation